Music Review: New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival 2018

Mostly the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival ends up being about the multiplicity and infinite variety of cultures and traditions, including generic funk.

By Jon Garelick

Irma Thomas at the 2018

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival presented by Shell. Photo: Douglas Mason.

I had just about given up on day one of this year’s New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (through May 6). Granted, the Semolian Warriors Mardi Gras Indian gang had kicked things off with the necessary invocation: the Big Chief, Spyboy, Flagboy, Wildman, and their retinue in feathered, beaded suits of green, blue, orange, red, and white, and a ferocious backlines of percussion — hand drums, bass drums, trap set, tambourines, and clanking cowbells. Summoning the spirits, that’s what we were here for!

And so this masked African-American crew did: “I got a pretty Big Chief, dressed to kill! …Hoo-nah-ney!” … “Sew Sew Sew” (about making those suits), “Shallow Water” (invoking slave days), “Hold ’Em Joe” and “Meet the Boys on the Battleground” (the ritualized tribal face-offs), accompanied by the popping cross-rhythms of that percussion section. There was barely a wisp of melody except for “Battleground”; everything else was contained in the roll of percussion and those chanting proto-raps. As the Chief or another gang member rapped, the Wildman, carrying a skull-topped staff and wearing his own bull’s-horn crown, glowered at the crowd. In the front row of the standing audience were the gang’s family members, with at least one toddler dozing in his mother’s arms.

Inspiring as they are, the Indians are but a prelude to each day of this two-weekend event, now celebrating its 49th anniversary, an appetizer, not the whole meal. (The festival, presented by Shell, continues May 3-6.) Yes the sun was shining over the Fair Grounds Race Course, with its 13 separate stages and copious options for excellent food. But after the Indians, and our requisite breakfast of crawfish bread (that is, if you didn’t count the beignets at Café Du Monde a couple of hours earlier), the day seemed to deflate. Famed Cajun-music revivalist and fiddle virtuoso Michael Doucet and his band Beausoleil made some interesting forays into Arabic-tinged scales over the traditional country two-steps and then brought on a so-so female vocalist as a guest for a couple of tunes. On the Congo Square Stage, Big Chief Donald Harrison Jr. — Mardi Gras Indian royalty and jazz eminence — was introduced as combining elements of “soul music, jazz music, funk music, and New Orleans music,” but the overall effect was of generic funk. Across the Fair Grounds, Harrison’s nephew, trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, struggled with blurry electronics in the reverb-heavy Jazz Tent. At the open-air Gentilly Stage, the overamplified boom did no favors for the British-born NOLA adopted son Jon Cleary, who is otherwise a charismatic pianist and singer.

Unfair judgments based on 5 or 15 minutes of listening to an hour-long set? Maybe. But there’s too much going on at JazzFest to indulge any weakness from a performer. After all, maybe Irma Thomas or even the mighty Rod Stewart is playing a few hundred feet away. And if not, you’re still required to partake of as much pheasant-quail-andouille gumbo (or crawfish bread or cochon du lait or countless other regional delicacies) as your stomach can bare.

Adding to this frustration, the Festival had instituted new security measures: a metal detector that slowed entry into the Fair Grounds to a crawl. It was enough to sour the mood from the get-go. And, then, for good measure, there were a couple of flyovers of fighter jets. “Are we at war?” my wife asked. (The security-check problem was solved by day two, and the entrance line moved quickly.)

In times like these, a seasoned and cranky festival-goer, navigating the fluctuating crush of as many as 70,000 other humans, can start to feel dark. Indeed the dancing second line in the trad-jazz Economy Hall tent, their parasols held high, began to suggest nothing less than the closing shot of “The Seventh Seal.” A bad trip, indeed.

But at 4:15, salvation arrived in the form of Samantha Fish, a young Kansas City singer and guitarist, recently moved to New Orleans. Fish had been highly touted, and the Blues Tent was packed to overflowing.

Tuba Skinny at the 2018 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival presented by Shell. Photo: Jacqueline Marque.

Fish lived up to the hype. She could sing (bright and strong and high, a rock-and-roll Brenda Lee or Dolly Parton? a post-rockabilly Wanda Jackson?), she could play (rhythmic riffs and digital dexterity that made her low-register chords growl and her high notes sing and howl in long arcs of melody). And she had songs (a favorite: a secularized gospel tune reminiscent of Irma Thomas’s “Breakaway,” with the rhythmic equivalent of eight-to-the bar handclaps). Her hair a red bob, and wearing a sparkling red, blue, and gold mini-dress, with knee-high black boots, Fish cued her band with downstrokes of her guitar neck, knelt on the stage to play with effects in dramatic dynamic shifts, and moved efficiently through her set.

So what made her guitar so special? Was there some Duane Allman in there? She knew how to articulate with a slide. And she avoided Stevie Ray Vaughn mimicry. The guitar was clean and precise, but throaty too. The important thing was that she used the guitar as an extension of her voice and her songs, and not just as a riff-generating machine. Her deployment of a trumpet-baritone sax horn section gave some of the music a bit of Dap-Kings retro jump-blues appeal and, for good measure, a violinist/violist complemented those guitar strings.

Thus were we were saved. By guitars! On a tip from a friend, we headed over to the Cultural Exchange Pavilion to hear Sidi Touré of Mali – it was another tonic. Here were three guitarists, including one who doubled on electrified ngoni, plus bass, drums, and a djembe player whose explosive smacks recalled the great Senegalese musician Mor Thiam. Here too was the characteristic Afro-pop weave of guitars, the rolling 6/8 that manages to be at once frenetic and relaxed, propelled by call-and-response between trap drummer and djembe player, between band and audience (“ey-yeh-yah!”).

We finished the day with bluesman Bobby Rush, now 84, pacing the stage like the assured showman that he is — white jacket, black t-shirt, powder blues slacks. He offered up the salacious fare he’s famous for, gesturing alternately to one of two female dancers in bright-colored skin-tight body suits: “Look at that.” One of the women, in bright red, had her back turned to the crowd, shaking it. “Look at it! When I see it moving like that. . . . It’s talking to me!”

He also played some fine blues harp.

Day one saved, we were ready to go. It was pushing 7, and the lines for the shuttle buses would be long. Sting was singing the Police-era reggae-fied “I Can’t Stand Losing You” on the headlining Acura Stage while, across the infield, Steel Pulse was playing the real thing on the Congo Square stage. On the way out, we heard Sturgill Simpson on the Gentilly Stage. “New” country. That was good too.

There was more. Way much more to be seen and heard those first three days of JazzFest 2018. Much of it profound. Didn’t some great German philosopher once say that all choices are bad? With 13 stages (including the kids stage) cranking from roughly 11 a.m. to 7 every night, the potential for bad choices can seem infinite.

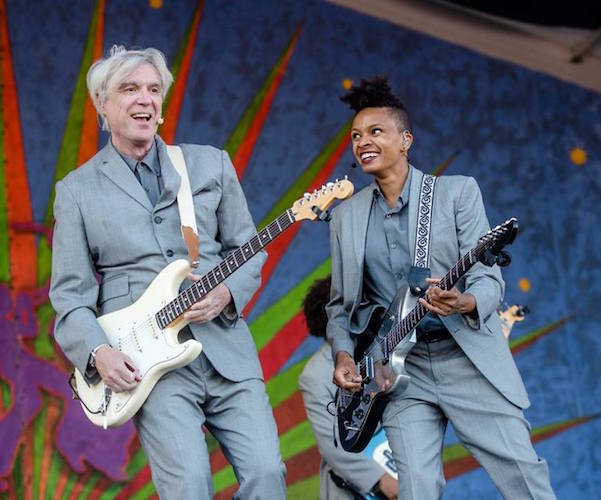

David Byrne at the 2018 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Presented by Shell. Photo: Joshua Brasted.

For instance, you’ve probably heard about David Bryne’s closing set on the Gentilly Stage that first Sunday (opposite, on the Acura Stage, Jimmy Buffett!). Yes, David Byrne was transcendent! David Byrne stole the show! David Byrne opened an audience of thousands to a new consciousness! David Byrne made America human again! David Byrne may even have saved the world!

But I was not there to witness it. While Byrne – an eminence gris (and these days truly gris) of “new rock” was performing that reputedly transformative show on the Gentilly Stage, I was at Economy Hall, trad-jazz heaven, watching a scruffy octet of thirty-and-unders called Tuba Skinny. Byrne was playing new music, with a new band. Tuba Skinny was playing King Oliver, Fletcher Henderson, early Ellington, other ancient fare, and choice originals written to sound old.

I couldn’t tear myself away. Bryne is bringing his show to Boston in a few months. Tuba Skinny rarely leaves New Orleans. Those are the kinds of calculations you make every day at JazzFest — the JazzFest math. You won’t see in Boston the fine young singer Meschiya Lake fronting a blue-chip band paying tribute to the all-but-forgotten NOLA jazz matriarch Sweet Emma Brown. And you won’t eat gumbo better than that pheasant-quail-andouille — anywhere.

And so it went. Irma Thomas, whom you’ve seen countless times, or Jon Batiste and the Dap-Kings? Reason dictates that you should see Jon Batiste doing something you’ve never seen him do before. On the other hand, sometimes you just have to see Irma. The Soul Queen of New Orleans opened with the hit “It Don’t Get Better Than This,” and then announced she’d be singing some “songs I haven’t done in a hundred years.” Reading lyrics from a music stand doesn’t play especially well on the Jumbotron in front of thousands. But then there was “You Can Have My Husband But Don’t You Mess with My Man,” and Irma, at 77, rolled into the song’s jubilant finale (“yeah-yeah-yeah!”) with gorgeous unforced power, still the Queen.

If Irma Thomas was living history – as were Jambalaya and the Savoy Family Cajun bands — Lake’s show was about rediscovering roots and reclaiming them. Sweet Emma Barrett (b. 1897) was a pioneering female pianist, vocalist, and bandleader, whose career extended from early blues and vaudeville through TV and film (she died in 1983), and Lake did the whole deal: from “I Ain’t Gonna Give You None of My Jelly Roll,” to “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” and “Bill Bailey.”

There were multiple tributes to New Orleans and Louisiana greats who had died over the past year — including a big Acura Stage all-star tribute to Fats Domino, Jambalaya’s dedication to D.L. Menard (“the Cajun Hank Williams,” who died in July of last year), and several offerings for another member of New Orleans royalty, Charles Neville, who died on April 26.

But mostly the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival ends up being about the multiplicity and infinite variety of cultures and traditions. Fred Starr of the Louisiana Repertory Jazz Ensemble said his band’s 38-year mission had been to “recover lost music,” but that project is also ongoing with Tuba Skinny, who look more like an indie rock band than trad jazz. Both bands played pieces by little-mentioned early-jazz composers like Sam Morgan, and both roared with grit and sass but also with delicacy. When Tuba Skinny played Ellington’s “Saturday Night Function” or the LRJE played Jelly Roll Morton’s “Black Bottom Stomp,” you could hear this music as both low-down and exalted, another kind of classical music, requiring faithful execution as well as exuberant spontaneity. Or as Fred Starr recalled Morton’s stern instructions to his musicians, “Play the little black notes.”

Jon Batiste with The Dap-Kings at the 2018 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Presented by Shell. Photo Credit: Jacqueline Marque.

As for the lowdown, Starr also solved a mystery: The early jazz tune “Winin’ Boy,” he explained, wasn’t about a wino or someone given to weepy complaints, but about “pelvic action” (“Don’t deny my name!”). So in that regard we had Bobby Rush, but also Big Freedia’s bounce crew, sampling “Rock Around the Clock,” Michael Jackson’s “Rock with You,” and Beyonce’s “Formation,” before breaking down into machine-gun beats and rampant twerking punctuated by disco air-horn blasts, Freedia whipping her blonde Beyonce wig.

There were allusions to the political and social climate everywhere (at Congo Square, Big Freedia fans waved a big pink flag emblazoned with the word “Freak,” and then those metal detectors were a reminder of the outside world). It was the kind of event where Lucinda Williams (in a collaboration with jazz great Charles Lloyd, in preparation for the release of a new album on Blue Note) sang Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” and Rod Stewart (alluding to an old collaboration with Jeff Beck) sang Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready,” and you’d be hard-pressed to choose one as better than the other.

And, of course, there was Byrne. Playing with the group from his new American Utopia. Byrne ended his show with a cover of Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout,” the band shouting repetitions of “Say his name!” And running down a litany: Emmett Till, Michael Brown, Amadou Diallo.

That closing number was the one Byrne performance I did hear. And I’m glad the word is getting around. Spreading the word is another of the great traditions of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. And another reason I can’t give up on it.

Jon Garelick is a member of The Boston Globe editorial board. A former arts editor at the Boston Phoenix, he writes frequently about jazz for the Globe, The Arts Fuse, and other publications.

Tagged: Bobby Rush, David Byrne, Irma Thomas, Jazz, New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, Samantha Fish