Classical CD Reviews: Peter Oundjian conducts John Adams and Leonard Bernstein conducts Mahler

Peter Oundjian and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra deliver a great album, smartly programmed and played to the hilt. Leonard Bernstein’s live Mahler was often electrifying; this performance, even with some cracked notes and hairy transitions, certainly is.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

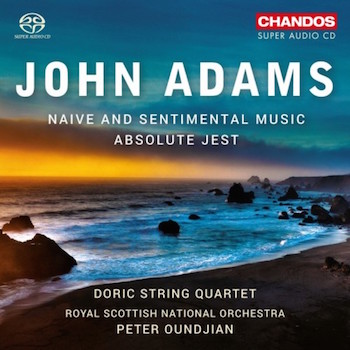

Peter Oundjian and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra (RSNO) follow up their triumphant 2013 John Adams album (comprising Harmonielehre and the Doctor Atomic Symphony) with a sequel that’s just as good – if not better, featuring Adams’ Naïve and Sentimental Music and Absolute Jest.

Naïve and Sentimental Music made a pretty big impression on its debut (Mark Swed called it “music people want to hear and should hear”), but it’s been only sporadically played in the U.S. over the last few years. Oundjian and his Scottish band remind us what we’re missing: a brilliant, often tuneful essay that shows Adams at the top of his game.

The first movement is well-shaped, Oundjian drawing out the subtle shadings of the opening theme to fine effect. And it never lacks for rhythmic energy, be that in the climactic outbursts or in the slight differentiations between dotted-eight/sixteenth-notes and triplet figures that repeatedly crop up.

There’s a marvelous sense of space – emotional and acoustic – to be found in the second movement, “Mother of the Man,” its guitar melodies played with touching delicacy by Sean Shibe. And the finale, “Chain to the Rhythm,” comes across as a pummeling romp.

Filling out the Chandos album is an exuberant and stylish reading of Adams’ string quartet-and-orchestra piece Absolute Jest. This is one of several major Adams scores that gleefully pillages Beethoven’s late period (in this case, mainly the last couple of string quartets), repurposing their materials in a decidedly contemporary framework.

Joining the RSNO here is the superb Doric String Quartet, who make themselves perfectly at home in the Adams’ hyperkinetic style. Their playing in Jest’s driving, rhythmic passages is nothing short of dazzling: perfectly in tune, uniformly articulated, and full of zest.

But it’s in the music’s extensive legato (or pseudo-legato) writing where the ensemble really settles in and shines, teasing out a bit more mystery and melancholy in the music than what came across in the work’s (still impressive) debut recording with the St. Lawrence String Quartet and the San Francisco Symphony (SFSO). Oundjian and the RSNO provide in a lively, colorful account of Adams’ orchestral writing in the score, in which the mean-tone-tuned piano and harp provide a sour bite, and the brasses sing radiantly.

In all, it’s a great album, smartly programmed and played to the hilt. It’s not too much to say that Oundjian and the RSNO turn in performances of these pieces that are at least as good as (if not better than) their debut recordings. Given that those were made by, respectively, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and SFSO, that’s saying something.

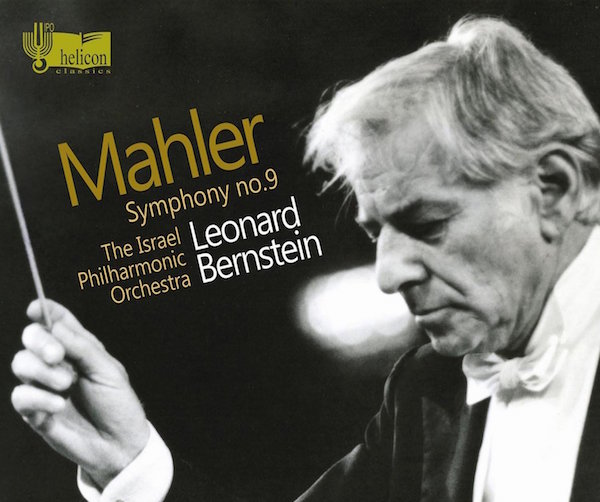

Leonard Bernstein’s take on the Mahler symphonies – emotionally-charged, highly subjective – was one of his crowning legacies as a conductor. Helicon’s rerelease of Bernstein’s 1985 reading of the Ninth Symphony with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (IPO) serves as a powerful, welcome reminder of this.

Bernstein’s Ninth is a very different one from Daniel Harding’s excellent, new recording for Harmonia mundi. For one, the recorded sound is less refined: the vagaries of a live performance (tentative entrances, audience noise, etc.) are all honestly captured. Balances are skewed at climactic moments (especially) towards the brass. Some of the score’s subtler textures get lost in the excitement of the moment. And the IPO doesn’t play with the same technical polish as does the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Still, there’s much to recommend it.

Bernstein’s live Mahler was often electrifying; this performance, even with some cracked notes and hairy transitions, certainly is.

The big opening movement is plenty spacious. Bernstein, especially in his later years, was a conductor who could linger over a tender melody here or a peculiar gesture there, and he does so, at times, in this movement. Yet his reading somehow never loses sight of the score’s architectural shape or the end-goal of the musical line.

A similar attention to detail dots the second-movement ländler: the slightly rushed horn grace notes near the first theme’s apex and the lingering flute trill just before the third ländler’s introduction lend this interpretation a certain piquancy.

The third-movement Burleske features some fearsomely aggressive string playing – under control, but just barely. It’s really edge-of-the-seat stuff that may not be to all tastes but, to these ears, is perfectly compelling.

For my money, the leaner, less-wrought Ninth finales of the likes of Gielen, Jansons, and Harding are preferable to Bernstein’s weighty, exaggerated interpretation. That said, he gets the music to sing beautifully and mines its expressive extremes better than, well, pretty much anyone. Even if you don’t buy Bernstein’s view of Mahler in his last years as a maniacally death-obsessed prophet, his is a approach that’s impossible to dismiss out of hand.

Those qualities make this album particularly welcome in a centennial year that’s already seen the sometimes rather unnecessary re-re-re-repackaging of Bernstein’s considerable Sony Classical and Deutsche Grammophon discography. This Ninth isn’t his best account of the piece – that would probably be his first, with the New York Philharmonic – but it’s awfully intense and considerably better than the uneven 1979 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Chandos, Helicon, John Adams, Leonard Bernstein, MAHLER