Visual Arts Review: A Delightful View of Edward Gorey’s World

The delightful Wadsworth installation is a fitting setting for the beloved artist and illustrator and the work he himself loved.

Edward Gorey, “It wrenched off the horn of the new gramophone,/ And could not be persuaded to leave it alone.” Illustration for “The Doubtful Guest,” 1957. Photo: courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum.

Gorey’s World at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, through May 6.

By Peter Walsh

Exactly why the illustrator, artist, and author Edward Gorey chose to leave his personal art collection to Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum remains, perhaps appropriately, an unsolved mystery. Gorey spent almost his entire professional career in New York City, where there are many suitable museums, and on Cape Cod, where his Yarmouthport house is now a museum in its own right. Born in Chicago and educated at Harvard, where he was a founder of the legendary Poet’s Theater, Gorey had no family connections or history in Hartford. The city and its museum were, apparently, a conveniently stopping off point between his Manhattan apartment and the Cape.

Besides that, the most plausible connection point was the New York City Ballet. Gorey was a ballet fanatic and a devoted fan of George Balanchine, the New York City Ballet’s founding artistic director. He typically attended over a hundred New York City Ballet performances per season. Unknown to many ballet fans, Ballanchine immigrated to the U.S. under the sponsorship of the Wadsworth’s pioneering director, Chick Austin. Balanchine’s pioneering School of American Ballet was founded in Hartford before it was lured off to New York.

The Gorey gift is not unprecidented. Elsewhere in the Wadsworth is an entire gallery devoted to the personal art collection of sculptor Tony Smith, given to the museum in 1967, following an important exhibition of Smith’s work there. The collection, made up mostly of works by Smith’s friends and contemporaries, includes major pieces by Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, and other important mid-century American abstract artists. Some art museums just get all the love.

The Gorey Collection and the Wadsworth’s Smith Collection make an interesting comparison. The Smith works are from a particular place and time, are by American men of roughly the same generation, and focus on a single medium: oil on canvas. Yet the individual artists are distinct and would not easily be confused with each other or with Smith.

The Gorey Collection works range in date from throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century and encompass prints, photographs, drawings, oil paintings, watercolors, and such exotic types as “sandpaper drawings.” The artists’ nationalities vary from American, Canadian, and English to French, Norwegian, Swiss, Flemish, and Japanese. They include such household names as Édouard Manet, Odilon Redon, Eugene Delacroix, Pierre Bonnard and Edvard Munch: New Yorker cartoonists like James Thurber and George Booth, anonymous folk artists, and artists known mostly to specialists and connoisseurs: Felix Valloton and Charles Meyron. Amongst them are displayed Gorey’s personal jewelry, one of his fur coasts, photographs of his homes and studio, and images of Gorey himself. Yet all this diversity blends so perfectly with the numerous examples of Gorey’s own work that many visitors no doubt miss where the artist leaves off and the collection begins.

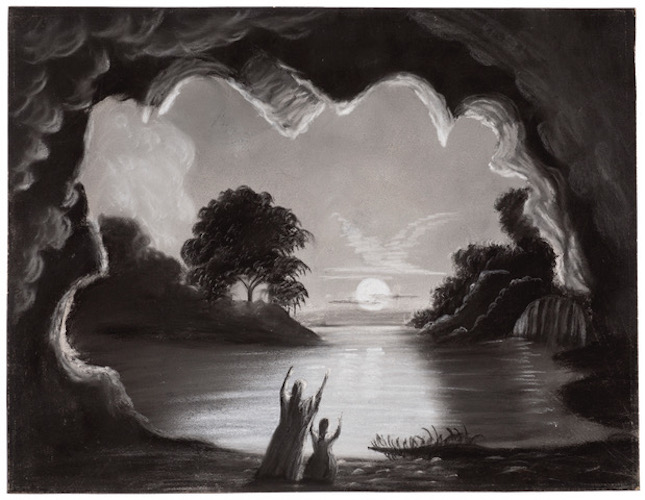

Unidentified American artist, “The Magic Lake,” c 1850. Photo: courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum.

In the Wadsworth exhibition, Gorey becomes a kind of artist-Zelig, or, rather,, a Zelig in reverse. Instead of making himself blend in seamlessly with the history of modern Western art Gorey makes two centuries of modern Western art look like Edward Gorey.

Just how does Gorey pull off this slight of hand? By a kind of triple selectivity — selectivity of scale, style, and sensibility.

Gorey spent most of his career creating cover designs for the more sophisticated paperback publishers and also, most famously, producing his own illustrated books, which center on country houses populated with degenerates or unidentifiable creatures with ursine profiles, children who meet amusingly macabre fates, and lonely ballet dancers. All the works in the show reflect Gorey’s own miniaturist sense of scale. And, although many of the artists on view are known for large, colorful canvases, the works Gorey chose to collect are heavily weighted towards prints and graphic works, many of them monochrome, like most of Gorey’s own drawings., and with literary overtones sympathetic to his books

Gorey’s collection of “sandpaper drawings” are a case in point. These are a type of New England folk art, created by drawing in charcoal on paper coated with marble dust, that create shadowy images perfectly suited to the British-influenced American-Romantic-Gothic movement made most famous by writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe. Gorey hung his sandpaper drawings over the fireplace of his Cape Cod cottage. Some of them, including “The Magic Lake” (ca. 1850), with their silhouetted figures holding their arms over their heads, look so much like Gorey it is hard to believe Gorey didn’t create them himself. Elsewhere, certain repeated visual themes — elegant domestic interiors and animals (dogs, cats, polar bears, cows, bats. insects, and strange yet somehow lovable creatures) — take up roles in Gorey’s work as well as in those of a range of artists from many countries and generations. Again and again, Gorey finds his own distinctive sensibilities in the artists he admired and collected.

Édouard Manet, “Cat and Flowers” (Le Chat et les fleurs), 1869. Photo: courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum.

As illustrated by a program he designed for the Poet’s Theater, created in 1950 while he was a Harvard undergraduate, Gorey matured early as an artist and his style remained consistent throughout his career. His appealing mix of whimsy and the macabre, along with his meticulous and distinctive graphic style and Victorian-Edwardian settings, seem to link him with 19th-century French and caricaturists like Honore Daumier, J. J. Grandville, and Felicien Rops (none of whom, interestingly, appear in the exhibition).

Yet Gorey’s biography makes clear that, despite a certain reclusive eccentricity, he was a modern, mid-century New York artist, living in the midst of the most advanced art of his own time. His college roommate was the poet and art critic Frank O’Hara and his designs for the 1977 Broadway revival of Dracula won the Tony Award for Best Costume Design. Some of his innovative illustrated books clearly connect him with conceptual art of the sixties and seventies. For all his aesthetic connections, though, Gorey remains, for better or worse, entirely his own man.

The delightful Wadsworth installation is a fitting setting for the beloved artist and illustrator and the work he himself loved. For once, the “educational” features fit in seamlessly with the show. There is a “ballet corner” complete with mirror, barre, and costumes to try on (obviously designed for children though, when I visited the gallery, mostly populated by cavorting adults), a recreation of Gorey’s New York drawing desk which visitors can explore with their own hands, and a video loop of Gorey’s well-known titles for the PBS series Mystery. It makes for a deeply satisfying whole, for those who meet Gorey for the first time as well as those select legions devoted to him for decades.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.