The Arts on Stamps of the World — December 3

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

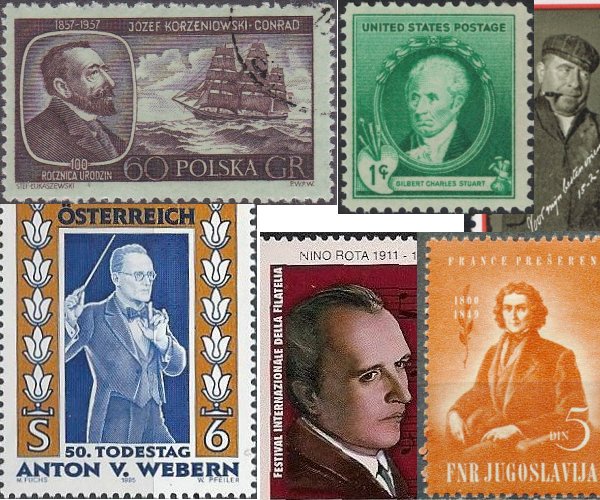

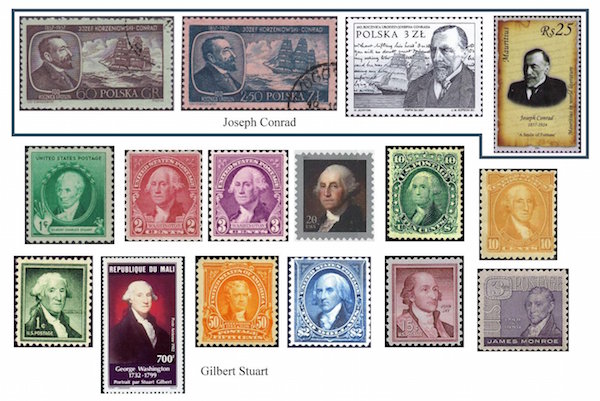

The pair of Polish stamps from 1957 was the world’s first philatelic acknowledgement of Joseph Conrad and the only one for another half century, a rather sad neglect, in my view, for one of the world’s great writers. Perhaps the Poles felt that, yes, he was Polish, but he wrote in English, and the British felt, well, yes, he wrote in English, but he wasn’t one of our chaps. (Of course, as I’ve said here repeatedly, the British have been notoriously reticent about honoring their great artists on stamps anyway. No UK stamps for Milton, Shelley, Pepys, Pope, Ben Jonson…get the picture? Luckily, other nations have from time to time stepped in to fill the need.) So, now, after fifty years, Poland has magnanimously seen fit to issue another stamp for their wayward native son, and Mauritius has gotten into the fray with one issued in 2008. I begin to feel a little better. You perceive that Józef Konrad Korzeniowski (3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) is one of my favorite writers. Certainly the film and television worlds have not been reticent about translating Conrad to the screen, but music has been slow to explore the wonders. Two operas have appeared just within the last few years, Tarik O’Regan’s chamber opera Heart of Darkness (2011, libretto by artist Tom Phillips), and Curtis Bryant’s The Secret Agent (2013, libretto by Allen Reichman).

American portrait painter Gilbert Stuart has himself been represented only once on a US stamp (the 1940 issue at upper left), but, of course, his portraits of presidents have graced many, many others. He was born Gilbert “Stewart” in Rhode Island on December 3, 1755 and died in Boston on July 9, 1828. When he was just fourteen, Gilbert met visiting Scottish portraitist Cosmo Alexander, who became the lad’s tutor and took him to Scotland. Alexander died within a year or so, and Stuart lacked the experience to make a living on his own, so he returned to Newport in 1773, but just two years later he crossed the Atlantic again and became a pupil of Benjamin West. Not only did remain with West for six years, but extended his stay in Britain and Ireland for a further dozen, coming “home” to Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1795. It was now that the series of famous presidential portraits got under way. The most famous of all, oddly enough, is a painting that was never finished. Stuart made a number of portraits of George Washington, but the original of the one from 1796 used for the image on the one-dollar bill (for well over a century now) and that appears on several stamp issues was left incomplete. Stuart used it as a model for the reproductions he produced at a hundred bucks a pop. This image, sometimes called “The Athenaeum”, we can see on a couple of stamps from the 1930s alongside a newer one with a 20-cent (one additional ounce) value, a full color issue from 2011. (To be clear, the current price for an extra ounce is 22¢.) Different Stuart Washington portraits have been used on stamps from 1861 (10¢ green), 1932 (10¢ yellow), and 1954 (1¢ green), among various others. This last 1795 portrait was also used for a stamp issued by Mali for Washington’s sesquicentennial. Stuart was the source for the images we see on the 50¢ Jefferson, $2 Madison (both from 1903), 15¢ John Jay (painting 1794; stamp 1954), and horizontal 3¢ James Monroe (painting c1820-22; stamp 1958) stamps. Stuart earned much cash from his efforts but was a poor money manager and was forever in debt. He moved to Devonshire Street in Boston in 1805 and is buried in the Old South Burial Ground of the Boston Common. He made portraits of more than a thousand people.

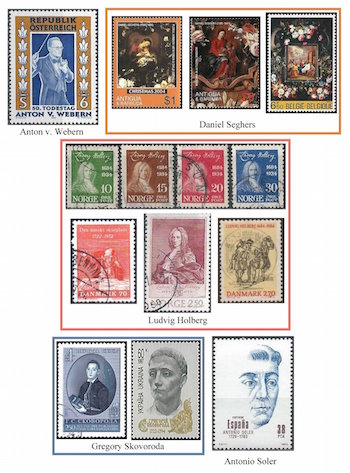

Austrian composer Anton Webern (1883 – 15 September 1945), with his teacher Arnold Schoenberg and his colleague Alban Berg, made up the holy triumvirate of the Second Viennese School, a movement with which many quite sophisticated music lovers still have difficulty a century after its founding. Webern was the most concise composer of the group, his works often characterized by a crystalline brevity. He was killed by an American soldier during the Allied Occupation when he stepped outside his home one evening near curfew to enjoy a cigar. The soldier was haunted by his action for the rest of his life, a mere ten years.

Time to turn back the clock for our less famous artists. Flemish painter Daniel Seghers (3 December 1590 – 2 November 1661) seems to have been exclusively a painter of flowers, oftentimes in what are called “garland” paintings, in which a central (originally sacred) subject is surrounded by flowers. All three stamps, two from Antigua and one from Belgium, demonstrate this, although the Antiguan ones concentrate on the central matter. For example, the first one, the $1 value, shows only the central detail from Floral Wreath with Madonna and Child. Seghers was born in Antwerp, moved in childhood to the Dutch Republic with his mother, who had converted to Calvinism, and returned to Antwerp as a young man, not only converting back to Catholicism but entering the Jesuit Order. This was in 1614, three years after his admission to the painters’ Guild of Saint Luke. His teacher was Jan Brueghel the Elder, no less. Seghers was in Rome for two years, working in collaboration with Nicolas Poussin. Then in 1627 Seghers went home to Antwerp, where his studio was visited by the High and Mighty, the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria, Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, Queen Christina of Sweden, and Charles II of England, and naturally by anybody who wanted to be seen with the artist who mingled with the High and Mighty. But his work also had its admirers from another form of nobility, I mean established artists like Rubens.

Also born on this date was the Norwegian-Danish writer, historian, and philosopher Ludvig Holberg (3 December 1684 – 28 January 1754). Holberg was extremely influential in Scandinavia both with his plays and his legal writings. You may be familiar with Edvard Grieg’s Holberg Suite for strings (it always amazes me that this music, so ideally suited to a string orchestra, started life as a piano work), but Grieg also wrote a Holberg Cantata in 1884. Johan Halvorsen wrote incidental music for Holberg’s Barselstuen (The Lying-in Room, 1911) and subsequently arranged the music into his Suite Ancienne, Op. 31, which he dedicated to Holberg’s memory. And American composer Dan Shore composed an opera (for six sopranos!), The Beautiful Bridegroom, in 2009. It’s based on Holberg’s last play. Norway and Denmark have each produced two Holberg issues: the Norwegian set of four small stamps came out for the 250th anniversary of the author’s birth (1934); the first Danish issue commemorated a different 250th, the one marking the first appearance of Holberg’s plays upon the stage. The other two stamps are tricentennial issues (1984).

The Ukrainian Gregory Skovoroda (3 December 1722 – 9 November 1794) was also a philosopher and teacher, but his artistic output consists not of plays, but rather of poetry and liturgical music. And he, too, is held as a seminal figure by his posterity. Indeed, such is his reputation that both Ukraine and Russia claim him as one of their own (so there’s a stamp from both countries). As a young fellow Skovoroda sang in the imperial choir in Moscow and St. Petersburg, returned to Kiev in 1744, and lived in the kingdom of Hungary from 1745 to 1750. Thereafter he was a tutor in multiple subjects (poetry, syntax, Greek, ethics). Skovoroda gave up teaching in 1769 and devoted himself to philosophy. He was also a gifted player on the flute and on the stringed instruments the torban and the kobza.

Antonio Soler was associated with a very different sort of stringed instrument, the harpsichord. He was baptized on this date in 1729. Like his older contemporary Domenico Scarlatti, he wrote a large number of keyboard sonatas (albeit only about 150 compared to Scarlatti’s 555) and served the Spanish royal family, ending up as chapel master at El Escorial. Whereas Scarlatti was an Italian, however, Soler was a native-born Spaniard. He took holy orders at the age of 23 and is thus known as Padre Antonio Soler. The most famous work attributed to him was a Fandango that is now thought to be spurious, but he wrote 350 other pieces, mostly sacred, beyond his sonatas. Soler died on 20 December 1783.

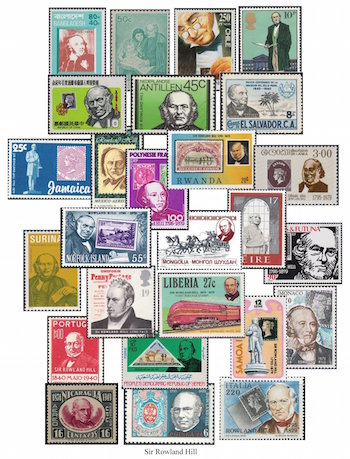

We would be remiss not to include Sir Rowland Hill (3 December 1795 – 27 August 1879), inventor of the postage stamp. He was also an English teacher (yay!) and education reformer. He has been remembered on hundreds of stamps from many nations (not the US, of course). I picked examples from Bangladesh, Belgium, Chile, Great Britain, China (Taiwan), the Netherlands Antilles, El Salvador, Jamaica, Mexico, French Polynesia, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Norfolk Island, Mongolia, Ireland, Wallis and Futuna, Great Britain (again), Liberia, Samoa, Monaco, Nicaragua, Poland, and Italy.

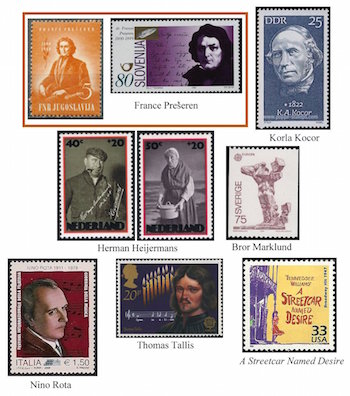

I admit to feeling a little abashed whenever I come across an artist of supreme importance to his or her country but who had heretofore been completely unknown to me. And so it is with France Prešeren (2 or 3 December 1800 – 8 February 1849), a Slovene poet seen as the father of Slovene literature and the greatest author of Slovene classics. France’s talent was recognized and encouraged early on, and he was a quick study, learning Latin, ancient Greek, and German (he did also write some of his works in that language) while still very young. He found further encouragement from the poet Valentin Vodnik in Ljubljana and attended university in Vienna, where his first serious efforts at poetry were written. In his studies of literature he found himself particularly attracted to the early Italians, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio (whose birthday is coming up on December 21). Prešeren routinely found himself at odds with the reactionary forces of his day—once he lost his teaching job for having leant a colleague a volume of forbidden poetry. He suffered the pangs of unrequited love, survived the early deaths of friends, turned to alcohol, and even attempted suicide at least twice, so it is not entirely surprising that his main themes tended toward the melancholy: unhappy love, hostile fortune, and the subjugation of his people under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In 1905 he was recognized with a statue in Ljubljana’s central square, now called Prešeren Square. His poem “Zdravljica” (“A Toast”) was set to music in that year by composer Stanko Premrl. It wasn’t performed until 1917, but was chosen as the national anthem of Slovenia in 1989. Since 1945 February 8th, the date of his death, has been called Prešeren Day, a national holiday. His image appears on a banknote and a coin, and the highest Slovene award in the arts is named for him. We have a stamp from Yugoslavia and one from Slovenia.

Korla Kocor (KOHT-sor 1822 – 19 May 1904) was a Sorbian (not Serbian) composer and conductor, born in Großpostwitz in what is today the southeastern corner of Germany. Thus his name is sometimes seen Karl August Katzer and his sesquicentennial stamp was issued by the DDR in 1972. He was only 23 when he wrote what came to be adopted as the Sorbian anthem, “Rjana Łužica” (“Beautiful Lusatia”). Ten oratorios constitute his largest body of work; he also wrote an opera, Jakub a Kata (1871), a Singspiel, Wodzan (1896), and chamber works including a string quartet, a piano trio, and three violin sonatinas.

Dutch writer Herman Heijermans (3 December 1864 – 22 November 1924) left a body of work including novels and plays as well as sketches reflecting Jewish family life. Possibly his best known work is the play Op Hoop van Zegen (The Good Hope, 1900), a story of the lives of fishermen at the turn of the century. The two Dutch stamps show Heijermans himself and the character Kniertje from the play.

Bror Marklund (3 December 1907 – 18 July 1977) lost his parents at an early age and was apprenticed to a carpenter. He began working as a sculptor in Stockholm in 1926. His early inspiration came from Aristide Maillol (whose birthday approaches in five days) and Charles Despiau (his birthday was last month, but fell during the period when The Arts Fuse was offline on account of technical issues). Marklund was awarded a stipend to study in Italy and France from 1934 to 1936. One of his pieces from this period is Sitting Boy (Sittande pojke, 1936). His sculptures can be found in Sweden’s major cities. The one seen on the stamp, Shape in Storm (1964), is situated in Trelleborg. (This title seems to have been used for a number of different pieces by Marklund.)

Giovanni “Nino” Rota (1911 – 10 April 1979) is thought of primarily as a film music composer, but he also wrote operas, ballets, symphonies, concertos, chamber music, and much more for the concert hall. Born in Milan, he was a child prodigy. He wrote an oratorio when he was 11 that was performed shortly afterward both in Milan and Paris. Of his 150 film scores, 18 were written for Fellini (8½, La dolce vita, Juliet of the Spirits, Satyricon, Amarcord, etc.) and four for Visconti, including La strada. He also wrote for Zeffirelli, Wertmüller, and Bondarchuk, and won an Oscar for The Godfather Part II in 1974. (He also wrote the music for Part I, of course.) In addition, Rota was the director of the Liceo Musicale in Bari for nearly thirty years.

And now for something a little (but not completely) different. The great English master

Thomas Tallis died on this date in 1585 (23 November is the date usually cited, but that’s by the Julian calendar, which was still in use in England at that time). He had been born about eighty years earlier, c1505. What’s different about this stamp is that it was never issued. It was a proposed design that, for whatever reason(s), the Royal Mail did not deign to accept.

The Tennessee Williams masterpiece A Streetcar Named Desire, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1948, opened on Broadway seventy years ago today, December 3, 1947.

He has no stamp, but the Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist (3 December 1922 – 20 September 2006) gets a nod from us regardless. Besides the Ingmar Bergman films he worked on (Cries and Whispers of 1973 and Fanny and Alexander of 1983 both won best cinematography Oscars), Nykvist also worked on Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice (1986) and on a number of fine American films, such as The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), Chaplin (1992), and What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.