Theater Review: New York Round-Up — “Junk,” The Red Shoes,” “The Band’s Visit”

The irony implied by Junk after the curtain goes down is the realization that white collar crime does pay.

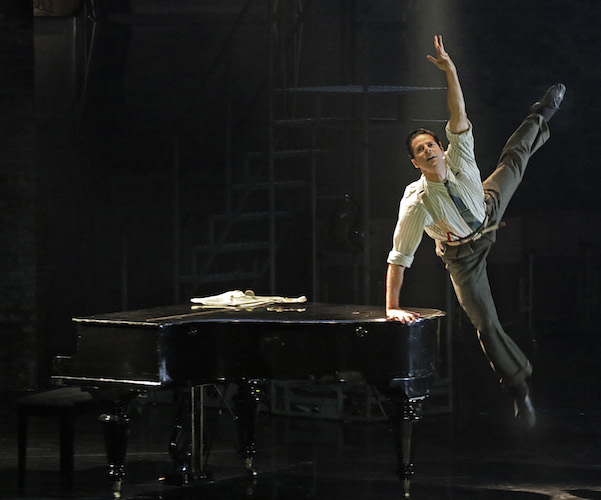

Marcelo Gomes as Julian Craster in production of “The Red Shoes.” Photo: Johan Persson.

By Iris Fanger

Matthew Bourne/New Adventures production of The Red Shoes at New York City Center, New York, New York, (closed on November 5).

Nothing could keep me from a trip to New York after the announcement that that Sir Matthew Bourne’s theatrical adaptation of the beloved ballet film The Red Shoes would play a two-week engagement at City Center as part of its’ autumn U.S. tour. I was nearly an adolescent about to start ballet classes in Chicago with a legendary teacher, Miss Edna McRae, when the movie was released in 1948. Although I was not destined for a ballet career, I embraced the ideal of suffering or even dying to for my art, the theme of the Michael Powell-Ermeric Pressburger film.

The film The Red Shoes is about the rising young ballerina, Victoria Page, who auditions for the troupe of impresario Boris Lermontov, and wins the leading role in his new ballet based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, “The Red Shoes,” with a score by the unknown composer, Julian Craster. Centering the film is the Lermontov troupe’s performance of the ballet of “The Red Shoes,” created by Leonide Massine, the most famous choreographer of the era, who also danced the role of the devilish cobbler. The red shoes that lure her from youth and innocence to doom in the ballet became the metaphor for the fate of Page, forced by Lermontov to chose between a career at the heights of the ballet world in his company or happiness with Craster, whom she loves. The film made a star of the young and gifted dancer Moira Shearer, highlighting her shimmering red hair, large eyes, and airborn laying out of gesture and movement — as if she were giving a gift to her audiences.

Bourne must have had some sense of foreboding about trifling with the iconic film when he decided to stage The Red Shoes for his company New Adventures. His adaptation eschews dialogue of any sort, even though the narrative’s complex relationships cry out for an explanation beyond body language, dance, and mime. Bourne has turned the film into a two-act ballet, one that closely follows Page and her dilemma. The problem is that viewers unacquainted with the film are surely going to be confused.

Some dialogue would have sorted out the story-telling, allowed Lermontov to explain his motives, and give voice to the longings and conflicts within Ashley Shaw, who plays the role of Page. Red-haired and wide-eyed like Shearer, Shaw delivered a detailed performance of the innocent girl in the corps de ballet who is thrust into the spotlight — but gives it up for love, to her sorrow. Marcelo Gomes, principal dancer at American Ballet Theater, alternated in the role of Craster. He dug deeply into his characterization while displaying his ballet expertise in several intense solos. Another indelible performance was delivered by Sam Archer as the cool but tormented Lermontov, also in love with Page (which differs from the character in the film).

Aided by Lez Brotherston, whose sets and costumes re-created the fashions of the post-World War II period, and Duncan McLean, who designed the imaginative projections for the ballet within the show, Bourne has staged a vivid spectacle, enhanced by an ever-turning, gilded proscenium arch hung with red velvet curtains that divides the backstage scenes from the dancers ‘on-stage’ performing several works, including a snippet of Les Sylphides.

Both the film and Bourne’s staging are filled with references to the Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which had folded less than 20 years earlier after Sergei Diaghilev’s death. Some of Bourne’s most effective choreography borrows from a pair of 1924 works by DBR choreographer Bronislava Nijinksa: “Les Biches” for the slinky, high society waltz by bored socialites, and “Le Train Bleu,” for the high-jinks of bathers on the beach at Monte Carlo, with the dancers garbed in period bathing attire, originally costumed by Coco Chanel. Bourne could not, and did not, surpass my memories of first seeing the film, but happily let me recall them.

Katrina Lenk and Tony Shalhoub in the New York production of “The Band’s Visit.” Photo: Matt Murphy.

The Band’s Visit at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 47th Street, Times Square, New York, New York.

The Band’s Visit is also adapted from a film, but offers a vastly different experience. Based on Eran Kolirin’s Israeli movie of the same name, this musical by Ithmar Moses (book writer) and David Yazbek is about ordinary people in a forgotten town in the desert, where nothing ever happens until an Egyptian band lands in the tiny main square by mistake. The band had been invited to play in Petvah Tikvah for the opening of the Arab Cultural Center, but bought bus tickets by mistake to Israel’s Bet Hatikva.

This story of the mismatch between Israelis and Egyptians, the former dressed in baby blue uniforms and lugging their band cases, focuses on the kindness of the locals to the confused travelers: they take the visitors in, feed them, and allow them a glimpse of their lives and problems. The scale is human, warm, and believable. Still, given the politics of the region, the mutual understanding on stage is probably no less a fairy tale than the Hans Christen Andersen story at the heart of The Red Shoes.

David Cromer, the brilliant director of the piece, knows his way around a small town as we saw in his production of Our Town several years ago at the Huntington Theatre Company. He has set the shabby buildings and small café at the center of several turn-tables; the effect is to give a flowing momentum to each successive scene to mark the passing of a single night.

Shalhoub who is well known to Boston theater goers for his roles in 18 productions over four seasons at the American Repertory Theater (before his starring stint on TV’s Monk) plays Tewfiq, the cautious, up-tight, leader of the Alexandria Egypt Police Force Band. He speaks English with a precise accent as if not to offend or overstep the boundaries for strangers in a strange land. In contrast, he is greeted by the seductive wild woman Dina, portrayed by the fabulous Katrina Lenk, who suggests a might-have-been to their relationship as the night unfolds. Andrew Polk as Avrum, an elderly but lively citizen of the town, is also a surprise musical performer, and a sympathetic character. (A Tufts University theater department graduate, Polk was the long-time founder and director of the annual summer Cape Cod Theater Project in Falmouth).

Who knew that Shalhoub could sing so well? Or the rest of the splendid cast for that matter? Each of them is required to become a musical performer, either singing or playing a musical instrument in the service of Yazbek’s Arab-Israeli infused score. By the time the band sits center stage to perform the music at the show’s finale, this unlikely but affecting theatrical experience seemed to have joined the actors and audience into a community, mutually applauding each other’s participation.

Joey Slotnick (center) and the company of Lincoln Center Theater’s prduction of “Junk.” Photo: T Charles Erickson.

Junk at Vivian Beaumont Theater, Lincoln Center, New York, New York, through January 7, 2018.

Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright Ayad Akhtar’s newest drama poses the question of how much is enough — of money, extracurricular sex, bespoke suits, and multiple extravagant houses — a wealth enabled by hangers-on and easy marks who help to elevate the smartest guy in the room into a king. The production replicates the amoral ease generated by the shadowy (and greedy) decisions made by a band of Wall Street newcomers in the 1980s that ultimately landed some of them in jail.

The title Junk (as in junk bonds) refers to the high-risk, high yield securities that drove the get-rich schemes of men like Michael Milken and Ivan Boesky. Although their names are not mentioned in the play, it is difficult not to consider them as ur-founders of this new ethically challenged breed.

Under the spot-on direction of Doug Hughes, the cast of 26 actors moves swiftly through a series of events that revolves around the take-over of Everson Steel, an old-line, family-owned company run by Thomas Everson, Jr. (Rick Holmes). Everson is rendered defenseless because of his concern for his workers and family tradition — principles hamper him from moving to protect his business against the raiders. The assault is led by Robert Merkin (Stephen Pasquale), master-mind of the transaction, and cronies Israel “Izzy” Peterman (Matthew Rauch), the take-over man, and Boris Pronsky (Joey Slotnick), who provides the insider information that fuels the deal.

Merkin is opposed by old-line financier Leo Tresler (Michael Siberry), who recognizes the approach’s danger to the old ways of doing business on Wall Street. However, it takes a dogged F.B.I. agent (Philip James Brannon) to bring the perpetrators down. And there’s more than a whiff of anti-Semitism in the air, given that the combat pits the old-line masters of the universe against the Jewish lawyers who are shoving them aside

Judy Chen (Teresa Avia Lim), a smart-mouth reporter-on-the- prowl, later to be seduced by the prospect of personal gain, not to mention the sexual high of an affair with the wealthy Tresler, serves as narrator. No less venal are the other women: Amy Merkin, the M.B.A. wife and stay-at-home mother who is the brains behind her husband and Jacqueline Blount, an Ivy League-trained lawyer who is writing the agreements while wondering why her pay-out is so much less than Merkin’s score.

The interdependency of the relationships plays out on a two story set, designed by John Lee Beatty and lighted by Ben Stanton, that divides the space into light-edged boxes, squares that mimic the machines that run the men’s lives in a world dedicated to offices.

Ultimately there are winners and losers in this game. Pasquale as Merkin is so sure of himself and his ability to persuade his followers that he talks himself into believing he can change the world. Ford, Coca-Cola, and General Electric are next on his target list — until one fatal error takes him down. However, after Junk‘s curtain goes down a sad irony hangs in the air: there’s the realization that, all said and done, white collar crime pays. Although barred from the securities industry and having paid a huge fine, Milken, now long out of jail, is one of the wealthiest men on the planet.

Iris Fanger is a theater and dance critic based in Boston. She has written reviews and feature articles for the Boston Herald, Boston Phoenix, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, and Patriot Ledger as well as for Dance Magazine and Dancing Times (London).

Former director of the Harvard Summer Dance Center, 1977-1995, she has taught at Lesley Graduate School and Tufts University, as well as Harvard and M.I.T. She received the 2005 Dance Champion Award from the Boston Dance Alliance and in 2008, the Outstanding Career Achievement Award from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts. She lectures widely on dance and theater history.

Tagged: /New Adventures production, Ayad Akhtar, Iris Fanger, Junk, Lincoln Center, Matthew Bourne, The Red Shoes