Jazz CD Reviews: Wadada Leo Smith — Paying Superb Homage to Monk, and Other Heroes

That’s why Wadada Leo Smith’s musical visions are so miraculous: there’s an impression of drift, yet they rarely meander.

By Michael Ullman

When I first heard Wadada Leo Smith—in Chicago in the late sixties—I thought of him as a counterweight to the saxophonists he performed with: his full-bodied tones, almost impassive at times, were a contrast to the edgier sounds of the musicians around him. (They included Anthony Braxton as well as the members of the AACM.) He was also different from the other trumpeters of the era (including Lester Bowie). At least since Dizzy Gillespie, many trumpet players have shied away from the demonstrativeness, the rich emotion, of Louis Armstrong and his followers. Gillespie’s bent tones and swallowed notes became an important part of the trumpet’s language, as was his at times oblique approach to the melody. (He had other qualities as well, of course.) Trumpeters in avant-garde circles — including Don Cherry and Lester Bowie — provided delights in a similar self-conscious vein.

Wadada’s penetrating sobriety and somber tunefulness proved to be a fascinating alternative. He played trumpet with an unabashed open horn, almost without vibrato, or with a vibrato so deliberate it seemed as if it was a separate thought. He sounded, to my ears, reverent, a devout humanist whose horn playing could be summed up by the title of one of his many ’70s albums — Spirit Catcher (Nessa Records). His song titles included “Human Rights” and “Black Fire in Mother-land My Soul.” 1978‘s six part trio recording was called The Mass on the World. He was optimistic as well as a religious. In the notes to Human Rights (Kabell, 1986), Wadada dreams openly: “A time must come, when an African child anywhere on the continent can walk from one end to the other, and never be hungry, never be in any kind of danger. A time must come when that child can walk the breadth of Africa and be protected by every eye that falls upon him.”

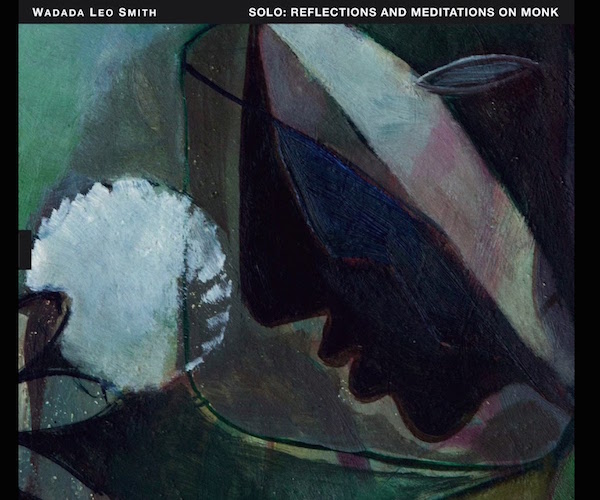

Smith’s latest recordings (both on Tum Records), Najwa and Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk, consist of tributes to, as well as evocations of, Wadada’s fallen heroes. Monk of course, is joined on Najwa by Billie Holiday, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. The exception to the homages on Najwa is the title tune, which Wadada describes as “a tragic song for a love lost” that he also sees “as a celebration of life and a clear understanding of love between a man and a woman.” The band, with four guitars (Michael Gregory Jackson, Henry Kaiser, Brandon Ross, Lamar Smith), electric bass Bill Laswell, and two percussionists (Pheeroan akLaff and Adam Rudolph), is remarkable for the nervy jumble of sounds it creates, as well as for its unusual instrumentation.

On the rest of the album Wadada is content to invoke, but not directly imitate, his heroes. His sublime and peaceful tribute to vocalist Billie Holiday (The Empress Lady Day in a Rainbow Garden) is about serenity; it is not a reflection on her troubled life or the mischievous swing in her voice. The piece opens with a series of long rounded tones from one of the quartet of guitars, who go on to assign themselves different roles in the tune. One plays long tones, another picks at a few spare chords, plucking out a metallic ring. Drummer akLaff plays a short roll on a cymbal and then subsides. Over this impressionist percussion Wadada plays the tune’s melody somberly, almost in slow motion. Each note hangs in the air, careless of duration; yet the piece never loses its momentum.

That’s why Wadada’s musical visions are so miraculous: there’s an impression of drift, yet they rarely meander. He gives his performers freedom — and they use it to help build the trumpeter’s world. His compositions’ soft musings are never boring or turn self-indulgent. Not all of Najwa remains peaceful: “Ornette Coleman’s Harmomelodic Sonic Hierographic Forms” begins with a jagged melody played in unison by trumpet and guitar — atonality is the goal, not contentment. A bass line asserts some order. After a pause, the tempo quickens (almost doubles). Wadada comes in with a frantic solo, a guitar comes in to prominently co-solo. And that is not all: Wadada thinks more of Coleman than the transparent melody of the opening, or the frenzy of the rocking group improvisation. The mid-section of this long piece is given over to the two percussionists, who solo over a repeated, dreamy guitar line that holds the pieces of this piece together. There’s more still: the drums come to a stop and, over the splashes of a cymbal, which maintain a tenuous beat, Smith plays a few beautiful phrases. They rise high into the stratosphere — without suggesting anguish.

In this year of Thelonious Monk’s (and Dizzy Gillespie’s) centenary there have been dozens of tributes to the pianist, but few have come along that are as distinctive as Wadada’s solo album Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk. Wadada seems to be musing on Monk’s melodies, remembering them fondly as he re-aminates them, phrase by phrase, starting off with the ballad Ruby, My Dear. Monk’s melody is so strong that its structure is only purified by Wadada’s affectionate deconstruction: the trumpeter plays one of its phrases, takes a breath, and then re-enters with a paraphrase of what Monk wrote. The tonal beauty of the performance here is breathtaking.

Wadada plays three more Monk ballads—”Reflections,” “Crepuscule with Nellie,” and “Round Midnight.” He also includes four of his own reflections on Monk, which were composed during various points of his career. First off there is the relatively buoyant “Monk and His Five Point Ring at the Five Spot.” Two of the pieces are marked adagio: “Adagio Monkishness—a Cinematic Vision of M Playing Solo Piano” and “Adagio Monk, the composer in Sepia.” The last number is set up as an impish enigma: “Monk and Bud Powell at Shea Stadium—a Mystery.” The piece came to Wadada in a dream: “It could be about the two of them at Shea Stadium, or perhaps not.” Clearly Wadada is amused at the idea of Monk and Bud going to a baseball game, or just hanging out. But on this disc he’s also looked for, and found, an exhilarating way to pay honor to the riddle of genius.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Najwa, Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk, Tum Records