Theater Review: Bravo for “American Moor”

American Moor is a terrific meditation on Othello and race.

American Moor by Keith Hamilton Cobb. Directed by Kim Weild. Staged by the O.W. I. (Bureau of Theatre) & Phoenix Theatre Ensemble at the Boston Center for the Arts, Plaza Theatre, Boston, MA, through August 12.

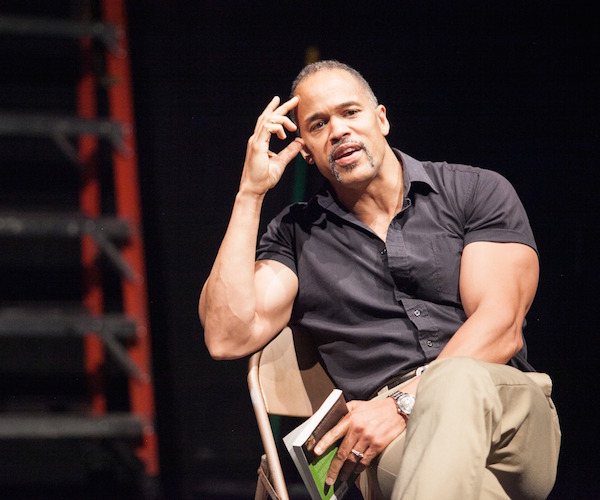

Keith Hamilton Cobb in “American Moor.” Photo: Courtesy of “American Moor.”

By Bill Marx

Thankfully, theater can still surprise, even a grizzled stage critic. No sooner had I written a piece complaining about the pablum spewed out by Boston theaters than into town arrives American Moor, a terrific meditation on Othello and race. Written and performed by Keith Hamilton Cobb, this provocative ‘meta-drama’ is not just a fierce expression of the performer’s love for the genius of Shakespeare and the complexity of Othello. The piece is a ringing defense of both in the face of a white theater establishment — high on liberal bromides — that cuts these unruly giants down to byte-size. Sometimes Othello’s diminution is the result of racism, sometimes his miniaturization comes from stale thinking and/or commercial pressures, sometimes the culprit is MFA training and its adoration of academic theory. Taking on these formidable opponents, Cobb raises a powerful personal objection: his refusal to accept the theatrical tried-and-true is humorous and passionate, political and philosophical.

Just to spread the blame around, here is how the black African writer Ben Okri characterizes Othello in his essay “Leaping out of Shakespeare’s Terror”: “It hurts to watch Othello as a black man … There he is, a man of royal birth, taken as a slave, and he has no bitterness.” Cobb’s American Moor delivers a blazing rebuke to this sentiment. Would Shakespeare write such a one-dimensional major character? A black warrior with no anger, no self-consciousness, no means to disguise his resentment at his treatment in the privileged halls Venetian white society? Cobb knows better, and he applies his understanding of life as an American black male, profession actor, to show the theatrical value of infusing the pain, vulnerability, and savvy of the black experience into the Bard’s figure. And along the way he points out that our white stage establishment is not interested in hearing what he has to say — comforting assumptions of control must not be challenged.

There is no reason for Okri to be ashamed of Othello — once you see the figure in all his capacious humanity. I won’t go into Cobb’s various (and interesting) discoveries, political/psychological interpretations that take us well beyond the gullible solider/lover of most Othello productions. I must admit it is rare to find a play that offers up revelations about a text that may startle even a veteran Shakespeare watcher. But Cobb does, especially with his suggestion that there is a boyishness in Othello, an innocence that I had always seen in Desdemona. In Shakespeare, innocence is incapable of defending itself (see Cordelia, etc). I had never realized that Othello and Desdemona share that primal weakness — a link that leads them to their doom.

American Moor focuses on Othello. Desdemona receives some comment; thankfully, the phony story that she falls in love with Othello because he is such a magical storyteller is discounted. Sexual attraction, yes, but Othello represents freedom from social conformity. Iago is barely mentioned; he is dismissed as “the white boy.” Cobb moves from satirizing his first acting teacher, who offered a cookie cutter notion of Shakespeare, to presenting an extended try-out for the role of Othello. Cobb auditions before the disembodied voice (Matt Arnold) of a white director who fires off amusing clichés about the nature of desire, etc., to which Cobb responds with internalized disdain. Sardonic observations are made about the anemic state of Shakespeare productions along the way, from Cobb’s desire to create an American tradition of robust performance to his complaints about budgetary restrictions in which productions are given scant rehearsal time to adequately explore the texts. Regarding staging Othello, can the distances between whites and blacks be overcome in such a short period of time? American Moor recommends dialogue between whites and blacks — but, given the breath of misunderstanding Cobb dramatizes here, can it realistically take place? And will today’s audiences accept the grand, volcanic acting that Cobb calls for? His performance adroitly veers from the muscularly fervent to the informal. Generations of audiences have grown up assuming that ‘good’ acting is epitomized by the minimalism found on TV and in the movies. And that ‘less is more’ aesthetic is increasingly shaping what we see on stage.

American Moor’s weakness is in how it rigs its argument. For example, Cobb caricatures the British tradition of acting Shakespeare in order to easily dismiss it. Yes, in the memorable words of critic Kenneth Tynan, John Gielgud was “the finest actor on earth from the neck up.” But the kind of visceral, exciting, in-depth performances Cobb demands have their roots in the efforts of Laurence Olivier and his followers. In terms of the script, the director becomes a cartoon figure, serving up lobs for Cobb to hit out of the park. And the text stops at a convenient point — when the director and Cobb could begin a conversation. Ending there is a bit of cop out; it would mean meeting the challenge of putting meat on another character’s bones. But these are minor objections to a wonderful celebration of Shakespeare. It would be fascinating to see Cobb play Othello but, in lieu of that, he has scored a distinctive triumph — he has done exquisite justice to one of the Bard’s creations.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

A fine review, Bill, and I second all you said of this wonderful production. Hail to Keith Hamilton Cobb, both as agile actor and, quoting Eric Bentley, as “the playwright as thinker.”

Thanks, Gerry — and for the mention of the marvelous theater critic Eric Bentley.