Classical Music Review: A Bleak “Black Monk” at Tanglewood

It is my sad duty to report that an evening which looked so promising was hardly a worthy homage to an important musical figure of the 20th century.

Shostakovich and the Black Monk—A Russian Fantasy at Tanglewood’s Ozawa Hall, Lenox, MA on July 19.

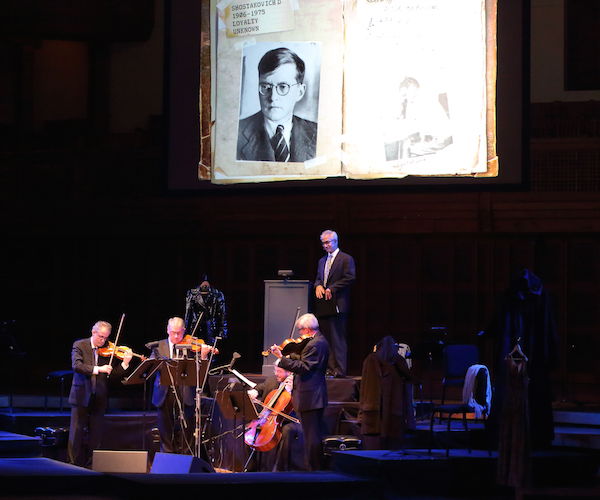

Emerson String Quartet performs “The Black Monk” at Tanglewood. Photo: Hilary Scott.

By Roberta Silman

One of the most memorable experiences I have ever had at Tanglewood was on August 9, 1975 when an announcement was made that Dmitri Shostakovich had died in Moscow at the age of 69. Guests that summer at Tanglewood were the great Russian singer Galina Vishneyevskaya and her equally great conductor husband Mstislav Rostropovich. Rostropovich was conducting that night, and before he took up the scheduled Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, Vishneyevskaya came on stage and sang a lament that I remember as a solo from the Verdi Requiem. This was still in the middle of the Cold War and having the Russians here was cause for ceremony. But to have them perform when their friend and countryman had just died was overwhelming, unforgettable.

Most things fade with time, but because Shostakovich is such a special case, the memory has grown in importance. For since 1975, especially after the end of the Cold War, we have learned in more detail how Shostakovich survived under Stalin and even afterwards, until he died. How his wildly popular 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (its full title was Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District) was denounced by the dictator himself in 1936 as “Muddle, Not Music” in the Russian newspaper Pravda. How Shostakovich from then on became a pariah in his own country. And how, although he made some attempts after Stalin died to placate the Soviet regime, it seemed that he could do nothing right. His music was denounced by his contemporaries either as “too Soviet” or “not Soviet enough.” And, apart from the political content of his works, and even the codes that may lie embedded in them, there are eminent musicians who consider him second-rate — Boulez and Esa Pekka-Salonen and James Levine are examples — yet there are also musicians such as Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa and Andris Nelsons who love his work. He was clearly a very complicated man, and it is worth mentioning a fine, fairly recent novel about him by Julian Barnes, The Noise of Time, that tries to untangle the many threads of his personality.

All of this is important to know when approaching this new work about Shostakovich that begins with notes he made about liking Anton Chekhov’s story “The Black Monk” and wanting someday to do something with it musically. He never got around to it but now, more than forty years after his death we have an homage in the form of “Shostakovich and the Black Monk—A Russian Fantasy.” It is a strange hybrid created from an idea by Philip Setzer and his friend James Glossman, performed by the distinguished Emerson String Quartet and a cast of splendid actors. The idea was to meld the Chekhov story with incidents from Shostakovich’s life and somehow add the music of the composer’s Fourteenth Quartet and other snippets of his chamber music. On paper it looks like it might work, and was co-commissioned by not only the Tanglewood Music Festival, but also Princeton University Concerts and the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival.

But good intentions sometimes lead to real disasters. Although there are obvious similarities between the hero of the Chekhov story and Shostakovich — profound doubts about their talent, the inability to make meaningful relationships and live in the real world, paranoia and fear of failure — the work performed the other night had no trajectory and seemed thrown on the page and, subsequently, on the stage. The actors were fine, but the writing is maudlin, too episodic, filled with too much shrieking and, in the end, had an edge of silliness that certainly didn’t help to reveal the dilemma either of Shostakovich or Chekhov’s character. And the photos in this “mixed media” production felt at times like part of a grade school production where someone was given the task of making sure the kids “got it.”

There were elements of the composer’s life that I recognized, e.g. that he spent many years sleeping fully dressed with a packed suitcase nearby because he was convinced that he was going to be taken off to the Lubyanka and killed, like his protector Marshall Tukhachevsky, or his refusal to live a monogamous life, or his love of smoking and vodka. But those are not enough. There was a story here, maybe starting with his love for a Chekhov story (although that seems a bit of a stretch), but this group has not imagined something fresh from the material they chose. Instead, they simply seemed to throw everything they knew about the Stalinist period, like the defection of Stalin’s daughter to the the United States, onto the stage in the hope that that would somehow lend the whole enterprise some authenticity. But art has to be shaped. A missed opportunity was to focus on how Shostakovich used the Shakespeare tragedy to create his initially well-received opera — until Stalin decided he was a music critic and changed Shostakovich’s life in a stroke.

In the program they emphasize that this endeavor is not a biopic, but something more “playful” and “impressionistic,” to be compared with the “fictions” of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn. They are dreaming. There was nothing in the evening that came anywhere the artistic accomplishments of either Stoppard or Frayn.

Moreover, it was a surprise to both my husband and me that a group as accomplished as the Emerson Quartet couldn’t have figured out a better way to bring in the music of the Fourteenth Quartet and thus show us what the fuss was all about. There was a fairly long stretch towards the end of the evening that was divine — his chamber music is really wonderful — but on the whole the music seemed to become less and less important, instead of the other way around.

So it is my sad duty to report that an evening which looked so promising was hardly a worthy homage to an important musical figure of the 20th century. It may also be worth noting that this was the first time we could remember the audience at Tanglewood being so lukewarm. After the final bow the usually enthusiastic Ozawa crowd did not call anyone back and there was a heavy, somewhat disheartened air as they made their way to the exits. In this era of tight budgets for classical music, I found myself wondering what the powers that be were thinking. How could anyone in his right mind give precious funds to such a misguided project?

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: "The Black Monk", Dmitri Shostakovich, Emerson Quartet, Shostakovich and the Black Monk—A Russian Fantasy

Just saw the same concert in Seoul. Terrible production and horrible script with dull screen art. Audience reaction was similar. I want my time back.