Film Review: The Complete Jean Renoir — Time for a Fascinating Experiment

The Testament of Dr. Cordelier is not a horror movie –it is more of a dark comedy.

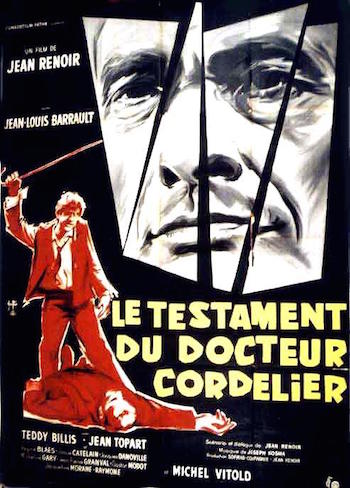

The Testament of Dr. Cordelier at The Complete Jean Renoir, playing July 21 at 9 p.m. at the Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, MA.

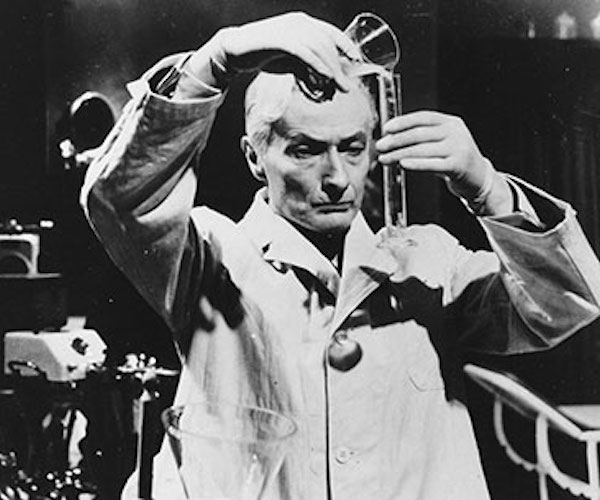

A scene featuring Jean-Louis Barrault in the lab from Jean Renoir’s “The Testament of Dr. Cordelier.”

By Betsy Sherman

We’re halfway through the Complete Jean Renoir film series at the Harvard Film Archive, and it’s been pretty damn glorious. There have been rarities to discover and classics to rediscover. We’ve come to know and savor Renoir’s pet themes (our needs for nature, art and performance) and notice others (I hadn’t before realized there was a whole thread of questionable mother/grown-son relationships).

Last month I wrote a paean to The Rules of the Game, which was the culmination of Renoir’s series of masterpieces in the 1930s. Many of these will play in late July and August: Boudu Saved from Drowning, The Lower Depths, Toni, A Day in the Country, The Human Beast, The Crime of Monsieur Lange, La Chienne, Grand Illusion, and a repeat showing of Rules.

The films Renoir made in his later years, from after the sublime The River (also repeating in August) to his last film in 1970, can be—for those other than die-hard fans—a mixed bag, although all of them have their rewards. For me, one of the highlights is his overlooked 1959 unofficial adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, called The Testament of Dr. Cordelier/Le Testament du docteur Cordelier. The movie has an alternate English title of Experiment in Evil and was released in the 3-disc DVD set Jean Renoir Collector’s Edition under the (boneheaded!) title The Doctor’s Horrible Experiment.

Produced as a sort of film-television hybrid for France’s RTF TV channel, Testament is not as aesthetically pleasing as the rest of Renoir’s work, but in terms of conception it’s rich and provocative. It wrestles with the great auteur’s trademark subject matter and gave two classic roles to that giant of the French stage and screen, Jean-Louis Barrault. The actor is best known for his performance as the lovesick mime Baptiste in Marcel Carné’s The Children of Paradise.

Testament is not a horror movie; Renoir didn’t have the absolutist outlook required for that, and besides, his movies usually combined or defied genre designation. Arguably, it’s a dark comedy—pre-dating Jerry Lewis’ 1963 Jekyll adaptation The Nutty Professor.

Renoir’s screenplay updates the novel to the modern era, and sets it in an affluent suburb of Paris. As in the original, the story is seen through the eyes of a lawyer. Here, it’s Joly, a notaire—in the French system, a contract lawyer, as opposed to a trial lawyer—who is also an old army buddy of the doctor. Acclaimed psychiatrist Cordelier—impeccably dressed, every white hair swept into place—is in Joly’s office, presenting him with a last will and testament that mysteriously leaves all his possessions to a Monsieur Opale. The doctor describes this man as an invaluable patient who has submitted to examinations of his brain. Joly is puzzled, and distressed. The lawyer is played by the squat, unremarkable-looking Teddy Bilis, a contrast to the sharp-featured, angular Barrault.

Testament complies with the fundamentals of the classic, as the atrocities committed by this supposed patient of the doctor become known to the lawyer and the authorities, who pursue the freakishly strong villain. The revelation comes late in the story that the doctor has been experimenting on himself, ingesting a formula that takes away the restraints of morality and unleashes a monster from within. In a contemporary touch, Cordelier’s confession to Joly comes not in the form of a letter, but on a reel of tape.

In retrospect, it seems quite natural for Renoir to have chosen this story. He had played with dualities before, and evinced a hatred of man-made borders; with the Jekyll story, he explores these issues within the body and the psyche. The filmmaker’s judgments always lay on a spectrum. Even his beloved rivers were destroyers as well as nurturers of life. In Testament, no one character is fully endorsed or fully condemned; they all have their “reasons.”

Consider a key line in the film he made directly after Testament. The modern parable Picnic on the Grass is one of the director’s most overt celebrations of the pagan over the civilized. In it, a pastoral wanderer proclaims that “in every man, a satyr sleeps.” He plays his pan-flute, which starts a chain reaction that topples the rule of rationalism and science (the flute is a symbol of freedom in Renoir, most obviously in The Grand Illusion). Robert Louis Stevenson may have been describing a similar awakening, but the Scot might not have been as accepting of the “satyr” as was the French son-of-an-Impressionist.

When the audience first sees Opale, there’s a definite slapstick element. He has coarse features, with puffed out cheeks, hairy hands, runaway sideburns and a mop of dark curly hair (the curls recall Harpo Marx, and there’s an element of Chaplin in him). His jaunty walk includes a set of twitches and tics—these are complemented on the soundtrack with a xylophone theme. The music may be cute, but make no mistake, Opale does some bad things. In his first scene, he attacks a little girl; later, he beats a man to death.

A violent scene from Jean Renoir’s “The Testament of Dr. Cordelier.”

If the doctor’s alter ego feels familiar within Renoir’s oeuvre, it’s because he’s closely aligned with the curly-haired primitive in the 1932 farce Boudu Saved from Drowning. Boudu (played by Michel Simon) is a contented tramp who’s physically rescued by a book-seller, who then wants to morally rescue the poor man with instruction in manners and a nice suit of clothing. The book-seller plays with fire by inviting Boudu, an agent of chaos, into his bourgeois household. Happily, the man-of-nature will not be tamed.

In a documentary series on Renoir that will be shown at the end of the HFA series, actor Michel Simon describes Boudu as “Adam before the fall.” This biblical metaphor is at work in Testament as well. During Cordelier’s recounting of his experiment, we witness the doctor’s first transformation (don’t expect any technical innovation here, or in the Opale makeup—all depends on Barrault’s skills in mime). Cordelier writhes in pain and crumples to the floor in fetal position. Barrault then unfolds himself like a baby bird emerging from an egg, wobbling its way to a standing position. The new creature is an innocent (for now). A nice touch is that Opale wears a larger version of the Cordelier suit, giving the effect that the doctor shrank into adolescence.

In contrast to Opale’s looseness, Barrault’s demeanor as Cordelier is stiff, pinched and dry. However, the aristocratic doctor can summon up charm; when he hosts a formal party for the Canadian ambassador, Cordelier puts on a mask-like smile (Renoir stages the soirée with such comic irony that it feels like pies should be flung).

It’s in flashbacks during the doctor’s confession that Renoir affirms that his is not so much a story about good and evil, it’s more about shame and liberation from shame (that Adam and Eve stuff again). When he was a practicing psychiatrist, he was known as “the virtuous doctor.” Although prudish, he was having an affair with his maid, but was conflicted about it (like it or not from our perspective, in the world of Renoir all maids are generous with their affection). Cordelier decides the affair is a perversion, and breaks it off. That action leads to him having sex with a seductive patient while she’s sedated (again, we won’t like this, but to Renoir the bad part is not sex with a willing patient, but doing it without her knowledge). After this, Cordelier ends his practice and devotes himself to proving the existence of the soul and to curing evil as one would cure infection with antibiotics.

Hollywood’s Jekyll adaptations have taken as a model a version that adds the female roles of a good-girl fiancée and a tart/whore. Testament does not, although it has a passage about Opale’s abuse of a prostitute in the licentious Pigalle district of Paris. Renoir chose instead to focus on Cordelier’s relationship with two male friends.

The first is Joly, of whom Cordelier makes a true confidant only when it’s too late. By foregrounding this character, Testament highlights issues of truth and trust. Renoir twice shows the metal plaque of the notaire, with its symbolic lady Liberté, outside of Joly’s office. It’s as if to say, here is a place where one goes for a guarantee of authenticity. Cordelier’s perverse last will and testament only underlines that this is a delusion. Bilis, though not a compelling actor, makes Joly rather touching: he’s a loyal friend whose trust is betrayed. Still, Joly is kind of a sycophant—Renoir takes him down a peg by having the notaire step in some poo on the sidewalk.

Then there’s the third member of this band of old friends. What are we to make of Dr. Séverin? As played by Michel Vitold, the bellicose psychiatrist is the anti-Cordelier, chain-smoking cigars, indulging all his appetites. It’s no secret that he and his secretary are lovers. The scenes set in his office play like sketch comedy (fans of mid-century modern will dig the sleek décor). Séverin is a rationalist, and denounces (at the top of his lungs) Cordelier’s search for a soul. So much for any respect of psychiatry.

Many of Renoir’s films have framing devices that are literal or figurative depictions of a theatrical curtain. Testament takes this to a new level. We see Renoir himself arrive at a television studio to introduce this “live” broadcast of a “shocking story.” Briefly, the audience is given a view from the control room. The faux realism makes for an odd, playful introduction.

The movie was an experiment for the director, who shot the interiors as if they were scenes of a play, using up to eight cameras at once (there are also several exterior scenes). Testament cost much less than an average feature film, and was shot much quicker. Herein lie its drawbacks. An even-ness in the lighting makes the interiors look antiseptic. The supporting cast lacks color, and scenes without Barrault can be draggy. One scene peopled only by Cordelier’s servants is particularly awkward (even though it features Gaston Modot from The Rules of the Game).

Testament was an experiment off-screen as well, meant to dissolve borders between the relatively new medium of television and film. The plan was to have a simultaneous television broadcast and theatrical run. But film professionals were angry that the new feature was going to be shown on state-run television, which would cut into ticket sales. The union of television workers was upset because their members were working on a film that would play in cinemas, but their pay level was less than that of film workers. Renoir’s movie was put on the shelf for two years before finally being broadcast in France on November 16, 1961, and opening the next day at the Georges V cinema.

Cordelier’s experiment was a tragic failure, but there is beauty in the fact that he followed it all the way to the end. Renoir’s experiment is worth witnessing, especially for Barrault’s double triumph.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Harvard Film Archive, Jean Renoir, Jean-Louis Barrault, The Complete Jean Renoir, The Picnic in the Grass, The Rules of the Game