Book Review: “Women in the World of Frederick Douglass” — Crucial Partners

Focusing on these indomitable and sometimes troubling women, Leigh Fought has written an engaging book that is compelling, sometimes even fierce, and extremely relevant.

Women in the World of Frederick Douglass by Leigh Fought. Oxford University Press, 401 pages, $29.95.

By Roberta Silman

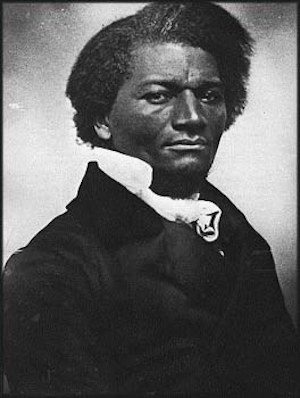

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was the most famous African-American of the 19th century. He lived a rich and fascinating life which influenced not only those of his own race, but also intersected with the most famous whites of his time. Photographs of him do not suggest his charismatic personality because, in keeping with the custom of the time he never smiled and when, later in the century, he was urged to relax, he refused, saying the last thing he wanted to do was to present himself as “The Happy Negro.” But he was clearly a formidable and very attractive presence, sometimes referred to as “The African Prince.” So it seems entirely logical that now, more than a hundred years since his death, we have this excellent biography about the women in his life by Leigh Fought.

Douglass’s early story is well known since he left three autobiographies, the most famous of which is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, first published in 1845 and reissued as a Penguin Classic in 1982. In this remarkable book, which amply displays his gifts for the English language, he describes his birth as the son of a slave, Harriet Bailey, and a white “master” whose identity he did not know. He was separated as an infant from his mother and spent his early years in the household of his grandmother, Harriet’s mother, Betsy Bailey.

Around the time of his mother’s death, when he was seven, he was moved to the estate of Aaron Anthony in the household of his “Aunt” Katy, probably a cousin, where, according to Fought, “violence and abuse did not always lead to sympathy and camaraderie, but instead, to more violence and abuse.” He escaped those years as an “abused, hungry child” when he was finally moved at age twelve to the Baltimore household of Hugh Auld where he met one of the most important women in his life: Hugh’s wife Sophia who treated young Frederick with respect and actually taught him the rudiments of the English language. Her tutelage lasted about a year until Hugh found out about it and convinced Sophia that such knowledge was the first step on the road to freedom and not appropriate to the life of a slave in the early 1830s.

But the die had been cast. Frederick was extremely smart and when sent on errands into the city he observed how men wrote and questioned them and was soon reading and writing fluently. Indeed, when his book came out — he was only twenty-seven — many people insisted it was far too polished and eloquent to be the work of a young black man. Moreover, he could speak as well as he could write. By 1843 he was giving speeches to the Anti-Slavery Society as a free man and he continued all his life to preach and speak all over the country and abroad.

How he emerged from slavery to freedom is entwined with the story of how he met his wife, Anna Murray, a free black woman. They were married in Manhattan when he was twenty and she was twenty-five. She was illiterate when they married and remained so all of their married life, which ended with her death in 1882; they had five children, one of whom died young, and she ran their various households in New Bedford, MA, Rochester, NY and Washington, DC with consummate grace, but preferring to stay — always — in the background. However, one of the most interesting points of tension in Fought’s dense biography is Anna’s place in his life: her forbearance when Frederick traveled to make his speeches, how she endured his long trip in the mid-1840s to England and Ireland where he marveled he found himself “treated not as a color but as a man,” and her relationship, (often bordering not only on jealousy but also on a kind of desperate hatred), with the various women Frederick befriended and actually brought into the household: women like the daunting Irishwoman Julia Griffiths who helped finance his Abolitionist paper North Star, and Ottilie Assing, the American correspondent for the German newspaper Morning Paper for Educated Readers.

Frederick Douglass — a formidable and very attractive presence, sometimes referred to as “The African Prince.”

Fought does a wonderful job of examining how “The Cause of the Slave Has Been Peculiarly A Woman’s Cause,” (her heading for her third chapter) and how Frederick’s ardent work on the cause of anti-slavery led him to engage in a kind of intellectual intimacy with many people, but especially the women who, in the end, often asked more of his time and energy than he was able to give. Of course, there were rumors, but there is no reason to believe Frederick was ever unfaithful; however, his passion for his causes didn’t make things easy for Anna. And after the Civil War, when anti-slavery became entangled with women’s rights, there were people like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony, who shared his mission but, as Fought slyly reminds us, could never forget he was African-American. The latter point has ironic resonances, and is one reason this book is so valuable. Just as Fought provides important details about a slave’s life in the early part of the nineteenth century, especially the way slaves were moved around with absolutely no thought to their family ties or needs or wishes, she also gives us those same kinds of important details about these now famous names in American and women’s history, thus giving us real insight into the complicated issues of race and racism at that time.

Fought is not only good in portraying Frederick’s relationship with his wife, but with his daughter Rosetta and her feckless husband Nathan Sprague and his sons, who seem to have had a sense of entitlement the patriarch did not admire and could not seem to prevent. At times, the Douglass family seems to be your typical dysfunctional American family. But, in the end, it was close and loyal and loving — mostly due to Anna’s remarkably strong personality. When she died, Fought tells us that “His grief at her passing suggested something beyond love, a loss of part of himself. ‘The main pillar of my house has fallen,’ he grieved. ‘Life cannot hold much for me, now that she has gone.’”

To everyone’s surprise, though, he married again in 1884, this time to a white woman named Helen Pitts, twenty years his junior, with whom he had worked in the Office of Deeds. Helen was a feminist, from an educated, abolitionist, well-to-do family, and their marriage caused consternation on all sides. As Fought tells us,

But even the most radical of antislavery activists supported miscegenation more in theory than in practice, and members of her family ostracized her after her marriage . . . abolitionism was only the starting point of her ideology, conditioning her to make decisions that placed her in the vanguard of interracial relations and shaping the way she understood her role as Mrs. Douglass into her widowhood.

One of the more interesting parts of the book is Helen’s back story, followed by the somewhat unsavory details of how she and his children were adversaries after Frederick’s death. But during the eleven years they lived together he and Helen seemed content and were often away, as Frederick continued speaking all over the United States as well as in England, Ireland, France, Italy, Egypt, and Greece during an exciting year in the late 1880s abroad. She seemed to do fine with Frederick’s newest protegee, Ida Wells, a young black activist, and although they were sometimes stung by those who saw their marriage as a stain against them both, they seemed able to rise above the criticism, even disdain, from both the black and white communities. And Helen worked tirelessly after Frederick’s death to maintain his legacy, mainly to insure that Cedar Hill became a public place.

But, for the children, Helen’s existence complicated the story and the legacy they wanted to tell. Indeed, as Fought reminds us, “his two wives represented two parts of a long life engaged in some of the most important events of the history of nineteenth century America and race . . .White women had always been part of his activism and had always played crucial roles in his survival.” Yet Anna had gotten him to freedom, reared his children, ran his homes, saved the money they needed to live as they did, and worked tirelessly for his success.

I must confess that I had no idea how complex Douglass’s story was. I had known only the first autobiography and also learned about him in a wonderful section of Colum McCann’s novel Transatlantic, which is a fictional recreation of his first trip to Ireland. But Douglass is a giant in our history and this new biography is a terrific way to begin to understand the daunting range of his achievement. By making its focus those indomitable and sometimes troubling women, Fought has written an engaging book that is compelling, sometimes even fierce, and extremely relevant.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

A delightful and enlightening review of this biography! I’m looking forward to reading it as a result of your profound description!