Visual Arts Feature: Artist John O’Reilly — Art History and Private Drama

“Well, it was quite a to-do. They had to get a police guard,” John O’Reilly says, a smile gathering at the corners of his mouth.

John O’Reilly: A Studio Odyssey at the Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, through August 13.

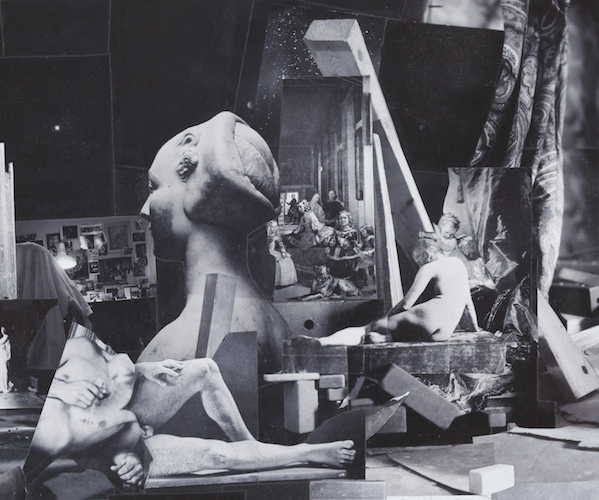

An excerpt from John O’Reilly, “Eakins Posing,” 2006. Polaroid photomontage.Photo: courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

By Timothy Francis Barry

Puritanical reactions to the alleged ‘scandalous filth’ proffered in cutting-edge art has long been a source of controversy to some and amusement to others. At the Paris Salon of 1884 an upstart New Englander named John Singer Sargent dared to depict his subject Madame Gautreau bristling with cleavage (the portrait, re-branded Madame X, is now at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). Paris salons hung the ‘dirtier’ pictures up high, well out of the range of men’s walking sticks. One day (during the 1950s) at Betty Parsons’ gallery in New York, the gallery owner noticed the word ‘shit’ angrily scrawled across a Mark Rothko abstraction. And who can forget the bulging blood-vessels on Senator Jesse Helms’ face over Robert Mapplethorpe’s stylized studio studies of the black male phallus, gay-fetish couples linked with chains, and his infamous bullwhip self-portrait?

In Andover, Massachusetts, in 2001, museum personnel at the Addison Gallery of American Art had to escort John O’Reilly out a side door at the opening of his exhibition. Why? An enraged patron had threatened to beat the then 71 year old photo-collage artist to a bloody pulp. “That garbage is anti-Catholic!” the visitor seethed. “And it’s not art! I know the trustees, I’ll get it taken down….”

In the sanctuary of his Worcester kitchen recently, on the eve of his largest museum exhibition since Andover, the quietly reflective artist recalls the moment. “Well, it was quite a to-do. They had to get a police guard,” he says, a smile gathering at the corners of his mouth.

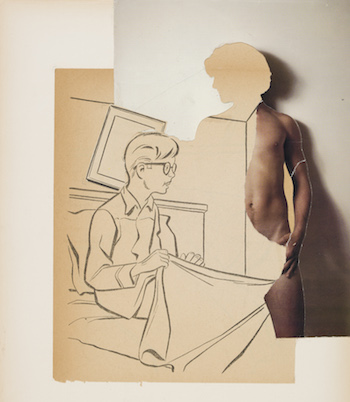

John O’Reilly, “Sailor Suit,” 2014, collage of found prints with crayon. Photo: courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

O’Reilly has never worried much about the public reception of his iconoclastic images, collages which may couple Jesus with a kneeling male poised for sex or place a Vermeer maiden’s head on a nude male body. One mash-up features his own naked self-portrait astride Gericault’s horse. He mixes-and-matches the sacred, the sexual, and the solemn, repurposing images from art history to create narratives for his own private purpose.

“My audience is me,” he explains, while walking a visitor through the steps of his analog, cut-and-paste method. “All of my pictures are self-portraits.” Regarding his creative process, he says there is no Photoshop involved; he does not even own a computer. His collages made by hand, in the tradition of the work fashioned by Hannah Hoch, Joseph Cornell, and Robert Motherwell during the last century.

His pictures are certainly surreal. But does he consider himself a surrealist? “That’s something I’ve been thinking about,” he says, settling his lithe frame into a wooden chair. “While they [surrealists) do go to the unconscious, I’d say ‘surreal’ in the sense of there’s a sublimation of violence, the fear of growing up [in my work]. Growing up in the ’40s and ’50s, I had to lie about my identity as a gay man. In getting ready for this show, I discovered that my art is really a form of therapy … for me.”

Working as an art-therapist at the Worcester State Hospital during the ’60s and ’70s was good training for O’Reilly’s distinctive investigations into the unconscious mind. Other artists have worked with mental patients; examples the come to mind would include Henry Taylor, the chronicler of African-American street-life, and abstractionist Chris Martin. But, for O’Reilly, encountering mental states of disorder and nightmare created a yearning for a kind of clarity, spurring a search for an almost mathematical balance that, in his work, becomes a kind of beauty.

John O’Reilly, “Apparition,” 2014, collage with found printed material. Photo: courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

His 2014 Apparition, a collage with found printed materials, centers on a fading image from a 1950s child’s storybook; a preteen boy wearing glasses sits up in bed, pulling the covers up over his midsection, as if he’s been caught in a ‘forbidden’ act. O’Reilly has seamlessly collaged in a photograph of a nude male torso gazing back at the boy. The bespectacled lad is O’Reilly in the past; the torso is a stand-in for the sexually mature O’Reilly.

These works require a lot of unpacking; you don’t get them at a glance. And that may be a drawback to this expansive exhibition; the 90-plus works are packed into two smallish rooms, and spill out into a hallway. Even the most sympathetic visitor may suffer from viewing fatigue after an hour or so. You need to spend more than a minute looking at each work to discover the richness of the nuances in the narratives. The pieces demand leisurely consideration.

A lot of thought went into contextualizing the works in this exhibition’s wall labels; literary episodes are often suggested as influences — a gay sex scene from Jean Genet’s mid-century novel Funeral Rites is displayed in the gallery for those who might stop to read the text. But what exactly are the links in O’Reilly’s work to the writings of novelist Henry James and the poet C.V. Cavafy? The lack of a catalogue or brochure to fully substantiate the speculation hampers a full appreciation of the connections.

Still, ambiguity is very much part of the program of John O’Reilly’s art. Ghosts drift through the shadow world of this visionary achievement. The artist’s amalgamation of the prosaic and the prophetic — his interweaving of the ephemeral, the muffled cries from the asylum, and fleeting images from an erotic dream half-remembered — give his work its indelibly haunting strength.

Timothy Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.