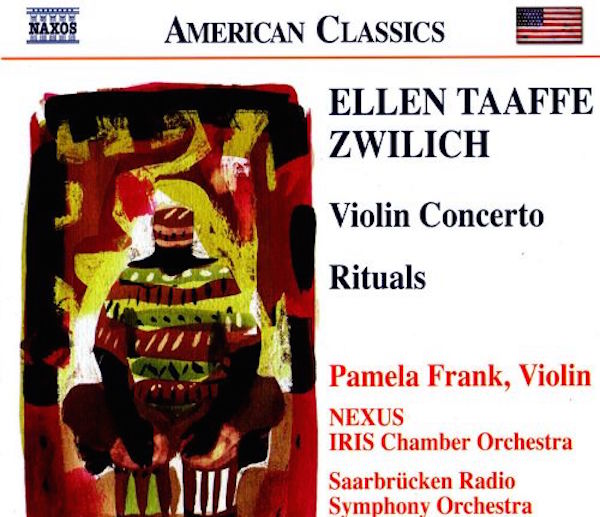

Rethinking the Repertoire #12 – Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s Violin Concerto

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twelfth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Over the last few centuries, most composers, if they’re also performers, have been accomplished keyboardists. Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Saint-Saens, Brahms, Mahler, Debussy…the list might go on and on. Much shorter is the tally of composers who are also noteworthy violinists. Here, after Mozart (an exception) and the fiddler-composers (Paganini, Bazzini, Wieniawski, et al.), one finds a much more select group headed by Elgar, Sibelius, and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich.

Like Elgar and Sibelius, Zwilich was an orchestral violinist of some repute before turning to composition – she played in Stokowski’s American Symphony Orchestra for seven years – and her catalogue boasts its share of pieces for the instrument. Then again, hers is a big archive, one that includes music for just about every major combination of instruments imaginable.

And it covers some wide stylistic ground, from hard-charging dissonance of Symposium for Orchestra to the neo-Baroque Concerto grosso 1985 to the pulsing rhythms of Rituals (last a four-movement concerto for percussion quintet and orchestra) and the jazzy riffs of her Clarinet Concerto.

What holds it all together? Several things. First, there’s often a tight unity of elements that reveal their relationships over the course of a piece. In the Clarinet Concerto, for instance, three of its four movements open with the same three-note figure: the first time it’s heard, the character is raucous and attention-getting; the second time, it’s drawn out expressively (that movement is a memorial to the events of 9/11); the last time, it’s elegiac, though less intense than before. What’s more, the melodic and accompanimental material of each movement incorporates this motive to an almost obsessive degree: exactly the sort of technique you find in, say, Bach and Wagner.

What’s more, Zwilich has an uncanny understanding of what instruments can do and how to showcase them best. Her Pulitzer Prize-winning Symphony no. 1 (she was the first woman to be so recognized, in 1983) demonstrates this with marvelous clarity: its sometimes spare scoring doesn’t waste notes or afford unnecessary doublings. But every instrument “sings” with brilliant, laudatory precision.

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich — her music is notable for its expressive depth.

Finally, Zwilich’s music is notable for its expressive depth. The Clarinet Concerto’s slow movement may have been a response to an event of overwhelming tragedy, but it’s not limited by that context: it evokes a spirit of sorrow and grief not constrained by time or place. Her emotionally-complex Celebrations offers far more ambiguity than its title – or galloping fanfare figures – initially suggest. And, in a rather different vein, her Peanuts Gallery, a piano concerto based on Charles Schulz’s famous comic strip characters, reveals a composer perfectly at home writing music of wit, style, and substance – a trait not many individuals who compose serious music (besides Shostakovich, at least) can pull off well.

It all adds up to an anthology of music of warmth, accessibility, and lyricism in a style that is entirely Zwilich’s own.

Out of it all, one of the most direct, moving, and satisfying examples is Zwilich’s Violin Concerto. Written for Pamela Frank and premiered at Carnegie Hall in 1998, its most striking feature is, perhaps, how relatively un-showy it is. There’s no excess of flashy, virtuosic writing. The scoring is, like the First Symphony, sometimes lean, though you never get the sense that something’s not happening that should be.

And that’s in large part because the writing is of a kind of spiritual intensity that’s rare to the concerto genre as a whole. Zwilich wrote a demanding piece, to be sure – the exposed, high-register solo writing is killer – but its intensity lies in more than just virtuoso ability. And its expressive rewards carry a longer, as a result.

Let’s take a look at it.

The first of the Concerto’s three movement begins with a long-breathed, cantilena melody exchanged canonically between strings and winds. After this, the soloist enters with a short cadenza outlining the significant intervals of the Concerto (namely, augmented octaves and minor ninths). An expansive melody that sits brilliantly in the instrument’s highest register follows, accompanied by the steady tattoo of plucked strings. Eventually, the orchestral cantilena reappears and leads to an energetic fast section.

There’s an almost spastic quality to Zwilich’s writing in this part. First, the music gambols through a series of hemiola figures. Then a dance-like section ensues. This is followed by more hemiola gestures that lead to an expansion of the opening cadenza.

After this, the music slows down a bit. The solo violin engages in some dialogues with solo flute and oboe. The opening cantilena recurs, now expanded to its greatest breadth and interrupted at a couple of points by violin arpeggios. One last cadenza leads to a cadence in the key of D major.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vY43mCcusjQ

The Concerto’s second movement takes on Bach. The orchestra’s accompanimental riff is drawn direct from the D-minor Partita’s “Chaconne,” over which the violin spins a long-breathed melody spanning much of its range. Other instruments – first bassoon, then low strings – take up ideas drawn from these two themes as the counterpoint thickens. The solo violin engages in some virtuosic demonstrations with the winds (there’s aggressive solo clarinet part).

As the music builds to a Copland-esque climax over thundering pedal Cs, the violin is nearly overshadowed. But the orchestral part breaks down and the soloist emerges, intoning, just before the movement’s end, the famous opening figure of the “Chaconne.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTxO47XvjwU

For the finale, Zwilich returned to the somewhat irregular character of the first movement. There’s much stylistic variety happens along the way: echoes of jazz and fiddle music are prominent, as is the searing lyricism of the second movement. But it’s all held together by Zwilich’s compelling voice, not to mention the use of gestures shared across movements.

Much of the movement is fast and there’s lots of syncopation to be found in the orchestral writing. Most of it can be tied to a short turn figure first played at the very beginning by the solo violin: how Zwilich develops this in combination with metamorphoses of earlier motives is one of the treats of discovering this piece. Suffice it to say, the movement progresses from its vigorous sections to a coda of serene, emotional honesty in such a way that it’s hard to imagine the piece ending in any other manner.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7e80pG_DKg

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.