Poetry Review: Lyrical Outrage — Songs of the Resistance

Many of the poems live up to the title’s shout-out to Walt Whitman by cutting through the current political miasma with fresh wit, insight, and lyrical outrage.

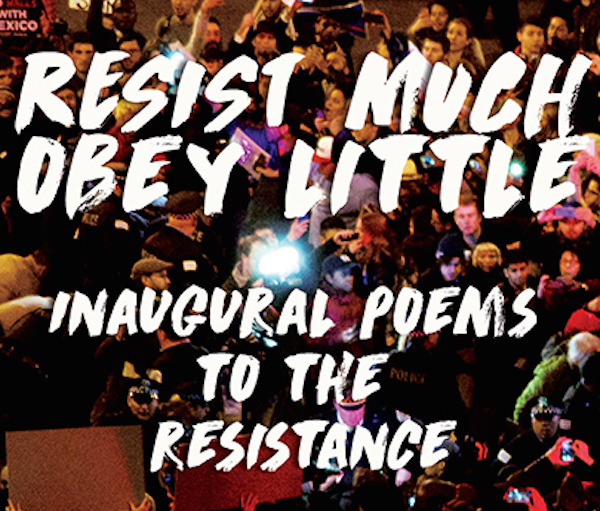

Resist Much/ Obey Little: Inaugural Poems to the Resistance. Spuyten Duyvil Press, 738 pages, $30.

By Matt Hanson

Spuyten Duyvil Press has recently published the Resist Much/ Obey Little: Inaugural Poems to the Resistance, a collection of an impressive amount of poetry written in the wake of the 2016 election. Many of the poems selected by the esteemed group of editors, including Nathaniel Mackey and Anne Waldman, live up to the title’s shout-out to Walt Whitman by cutting through the current political miasma with fresh wit, insight, and lyrical outrage. In a better world, copies would spontaneously appear in coffee shops and bars across the country like Gideon Bibles, not only because the country could use some rabble-rousing poetry right now, but also because half the proceeds of the hefty book will be donated to Planned Parenthood.

Some poems focus on the immediate reaction to the election results, registering the trauma of it all. Mercedes Lawry sums up the mood on “November 9, 2016” with the perfectly simple but evocative sentence, “It is a brittle day.” Robert Priest’s “The Revenge Fuck” lays it out like this: “we chose him for what he was not/ we chose him for maximum hurtage/ we chose him in anger/ and on a whim/ and now/ we’re stuck with him.” Ken Letko takes a different approach, writing with a staccato urgency in “Election Follow Up, 2016” to wryly remind us of an inconvenient fact: “don’t worry/ Social Security/ and Medical/ are fine/ the president elect/has navigated/ bankruptcy/ a half/ dozen times.”

The 2016 election was especially scatterbrained, even by the verbose standard of American Presidential campaigns. When Les Moonves, the CEO of CBS, confessed that Trump might not be good for America but he sure was good for CBS’s bottom line his remark was both painfully crass and terrifyingly honest. The election was seething with surprising plot twists and fed off of insistent, incessant media updates that we all became addicted to. Given that one candidate crafted her public statements through committees while the other used words like a dog gnaws on a chew toy, it’s delightful to hear the poisonous nothingness of such vapid political rhetoric turned on its head.

Patrick Lawler’s “The Last President” opines things like “winning/ is tremendous and those/ who are losers are stupid-/ but he would never say that.” Our 45th President probably has indeed said that, whether directly or indirectly, and more importantly he seems to believe it, just like when he says that he has the best words, “we know we should/ be impressed/ very/ impressed.” Some of us still are, sadly, but for those who care for language — at least enough to believe that it should be used with precision and honesty — the daily abominations Trump perpetuates on the American language are not forgotten or forgiven. As Norma Cole’s “Hard Candy” incredulously states: “The man/can’t/read.”

R Zamora Linmark’s “TrumpSpeak: The Next Four Years” takes inventory of Trump as brand name and expletive: “Eat trump and die./ Take a trump./ You trump./ Mothertrumper….Pro-trump missles./ Anti-cruise trumps./ income-tax retrumps…Trump or dare?/ True or trump?/ Trump you./ Trump you, too.” There’s plenty of Trump caricature in these pages, cartoons that use wit to fend off monotony, such as a description of Trump’s ascent (and inevitable downfall) as a new chapter in the nonsense verse of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” or as a delightfully cracked Dr. Seuss nursery rhyme.

Part of the tragedy of the election wasn’t just its hyperbolic hysteria, but how its tabloid excesses reflected much of the national mood. Both the candidates and their supporters fed off of anger and frustration to the point that the usual social niceties melted away. Marwa Helal’s “In The First World” vividly describes this apocalyptic ire:

“people arrive at cubicles in a rage.

At day’s end, they

Punch bags

Hanging from the ceiling,

Fight their reflections in the mirror,

Sprint on padded treadmills,

While a cop sleeps outside in a car-

Its engine running.”

One poet helpfully suggests that Trump should read “two to five poems a day/ depending on his schedule.” It would be an amusing experiment, if nothing else. Christopher Brown’s “…And The American Way” plaintively asks, “Trump trumped us all/ but did he really?” The answer is, of course, yes and no. Many were fooled, though even more were not; some in our society have already been in the soup long enough to have lost the luxury of being fooled at all. Others, represented by Moonves, figure that there is Plenty of money to be made.

Poetry is by nature an act of witness, a way of allowing unacknowledged suffering to speak. Dean Kostos imagines the last moments of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed West African immigrant with no criminal record, who was shot 41 times by New York City police in 1999. Ice cream that “tasted like America” is his last meal. Nancy Agabian delicately explores the ironies of identity politics through the story of her immigrant aunt, a survivor of the Armenian genocide, who changed her name to fit in as an immigrant child. The woman scoffs at the idea of bilingual education, asking “Why should children who speak Spanish get/ special treatment?”

The Chilean poet Nibaldo Acero wonders “what can this poem do/ beyond rallying against virulence/ fostering the uprising of others” and proposes a daily regimen of “thirty minutes of overflowing compassion, thirty minutes of frustrated sincerity/ of mutilated angels/ who do not understand why a giant/ who has never met them despises them so much.” Pierre Joris covers a lot of sociopolitical ground with a devastating wisecrack: “Yes, this is the Titanic./ Yes, those are icebergs./ No, upgrading to first class/ won’t save your ass.”

Someone once asked Samuel Beckett why tiny Ireland birthed so many great writers. His response was reasonable — when you’ve woken up in the last bloody ditch, he reportedly said, the only thing left is to sing. Andrea Hollander’s “In the Dark Times” quotes a famous line from a Brecht poem: in the dark times there will still be singing, but it will only be “about the dark times.” The midterm elections are glimmers — faint hopes far on the horizon. One thing we can do in the meantime is to listen to dissenting voices clamoring to be heard. We must not let them be pushed into the margins when the inevitable players — in the media, big business, and elsewhere (all profiting from disaster) tell us that Trump “isn’t so bad.” As Hollander’s poem gracefully explains, the many hilarious, moving, and sometimes galvanizing poems in this collection are “at least the match we strike/ again and again/ in the darkest dark.”

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Donald Trump, Matt Hanson, Resist Much/ Obey Little: Inaugural Poems to the Resistance, political poetry