Music Feature: Peter Kuhn’s Long Journey to “The Other Shore”

Peter Kuhn, a master jazz improviser, returns after decades away from the music.

Peter Kuhn on the bass clarinet. Photo: Peter Kuhn.

By Noah Schaffer

About 15 years ago a California reptile dealer’s phone rang. Peter Kuhn expected it to be the typical query about the rare pythons he was breeding.

Instead, the voice on the other line belonged to journalist and label owner Michael Ehlers, who asked if Kuhn was the same person who had recorded a small but memorable series of free jazz recordings in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

Kuhn confirmed that it was him, but the conversation didn’t last very long. Kuhn’s success in the jazz world didn’t slow down his decline into drug addiction, which eventually led to jail time. When he got the phone call, Kuhn was clean and had distanced himself from music and his career; he was focused on his business, family, and maintaining his physical and spiritual health. His past as a master improviser “was so far from consciousness — I couldn’t fathom that it was a serious call,” he recalls.

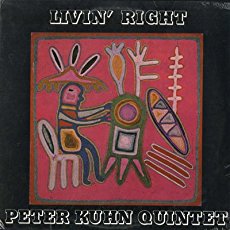

A decade later, a different journalist and producer, Boston’s Ed Hazell, tried Kuhn again. One of Hazell’s favorite recordings, Kuhn’s self-released 1978 LP Livin’ Right, had been out of print for decades. Hazell wanted to see if it could be reissued.

This time around Kuhn had a different response. He’d kicked a long-running battle with Hepatitis C, inherited an alto saxophone from a musician friend, and had been quietly making music again with friends in the San Diego area. Some were pressing him to resume his music career. A fellow musician, who Kuhn was sponsoring in a 12-step recovery program, couldn’t understand why Kuhn wasn’t prouder of being an artist.

Kuhn and Hazell kept in touch, and the end result was the release of No Coming, No Going – The Music of Peter Kuhn 1978-1979 on the Lithuanian NoBusiness label. Hazell and co-producer Danas Mikailionis paired tracks from Livin’ Right with a second CD, a newly uncovered 1979 live recording that had been made in Worcester with Kuhn and drummer Denis Charles.

The project earned a spot as one of the top 10 reissues of 2016 in NPR’s annual jazz critics poll. Now Kuhn has stepped back into the free jazz world via a newly recorded trio session for NoBusiness, The Other Shore.

Kuhn’s return to improvised music was a long and gradual one. While in the grip of heroin addiction he had sold most of his horns. After he’d traded in the drug life for a new career and family he’d occasionally play with friends, but immediately lost interest when his pals’ blues combo wanted to turn professional and perform in local bars.

“Most of the profound changes in my life have been brought about by some kind of suffering,” confesses Kuhn. “Getting clean was certainly one of those things.”

So was his return to music, which came at the end of a long and difficult period during which Kuhn lost a son, faced serious medical issues, and became divorced.

“I had been playing a bit with Caroline Romberg, a saxophone player in California, and when she died she left me her alto saxophone. I started playing more because it was a way of connecting with her spiritually,” he explains.

Kuhn also got a surprise gift of a clarinet from longtime collaborator Dave Sewelson. Playing daily got his chops up, but he still didn’t have other musicians to play with, neither did he “know what [he] wanted to say musically.”

“In Buddhism we talk about how things arise when conditions are adequate to support them and they cease to be when the conditions are no longer there. Well, I had the conditions and I was having fun — but I didn’t know any local players.”

That changed when Kuhn discovered a creative music community in Southern California that includes drummer Nathan Hubbard and bassist Kytle Moti, both of whom are on The Other Shore.

Kuhn’s early struggles with addiction predated his involvement with jazz. As a teenager he spent time at a California rehab clinic, where he ended up rooming with jazz legend Art Pepper, who references meeting “a young guy, the son of a doctor …this kid Peter Kuhn” in his gritty autobiography Straight Life.

Already a free jazz enthusiast, Kuhn says he became part of the music industry because it was one of the few professions that would allow him to be high, constantly. “For many years the drugs and music were linked,” he recalls. “For players the challenge is to quiet the mind and turn off the internal dialogue. I had a hard time focusing — while playing I’d be thinking about where will this go, is this hip enough — I had a real hard time stopping that internal monologue.”

Kuhn quickly found acceptance when he moved from the West Coast to New York in the late 70’s at the height of the free jazz “loft scene.” He gained particular notice as one of the few clarinet players to work in the creative scene, along with Perry Robinson, whom Kuhn is quick to cite as an influence. Kuhn’s recent work reinforces that his adroit use of the bass clarinet remains one of his trademarks. Ironically, the clarinet has often been the instrument of hotshot virtuosos, something that Kuhn insists he’ll never be. “Playing with limitations is the height of creativity,” he remarks. “And I thought I’d lose my edge if I became more practiced. But now the more proficient I am on the instrument the better I can express what is in my heart.”

The personnel on Livin’ Right featured some heavy hitters, marking an early appearance on record by William Parker, who has since become one of creative jazz’s most respected bassists, composers, and arts advocates.

“We all lived on the Lower East Side. Arthur Williams lived across the street and I heard him practicing. Frank Lowe lived around the corner. William was just a wonderful neighborhood guy. He is so heartfull and spiritual and so naturally grounded,” enthuses Kuhn. “Even in those days he was a shaman.”

The archived Worcester recording was discovered when Hazell asked WCUW jazz host Jim Capone if any of the recordings made by engineer John Voci had survived. Capone looked and found a huge trove, including the Kuhn/Charles set, sitting in a corner of the studio.

“I was amazed when Ed came up with it — I had no idea the concert was recorded,” says Kuhn. “It is very stark and vulnerable music. It’s hard to listen to — I had mixed feelings about releasing it. But now I’m glad it’s out there. There’s such inspired playing by Denis Charles — he’s so happy.”

Kuhn recently finished a tour of the Northeast to promote the new album. (His appearance in Cambridge on March 14 was cancelled due to a snow storm. The date came about because he was already scheduled to be in the area facilitating a meditation retreat for men in recovery.). His new musical pathway lets him create art that compliments his first priority, which he describes as communicating “that freedom from addiction is possible for everyone with a desire to stop using.”

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka and far beyond. He has won over ten awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.