The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 8

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

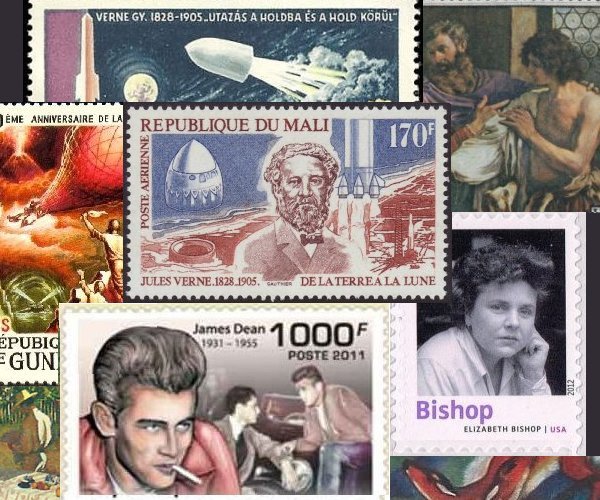

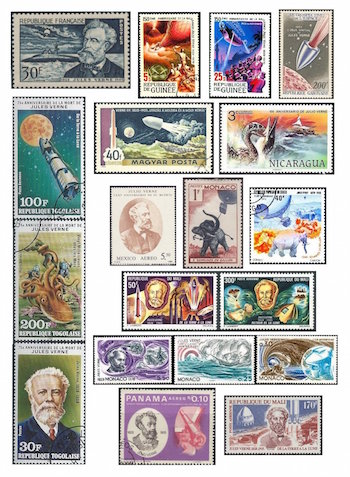

The sheer number of Jules Verne stamps boggles the mind nearly as much as do the author’s fanciful fictional conceits. Verne (8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) has thus caught the imagination, not only of readers and filmmakers, but obviously of stamp designers all over the world. The picturesque stories lend themselves well to picturesque stamps. The oldest, though, is a more-or-less straightforward homage to the writer (he also wrote poetry and plays), issued by France for the 50th anniversary of his death. Among the other stamps are evocations of Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), and The Mysterious Island (1875) from countries as wide-ranging as Guinea, Gabon, Togo, Hungary, Nicaragua, Mexico, Monaco, Congo, Mali, and Panama. There are many more not shown here. (In a quaint error, one of the Malian stamps refers to Retour de la Lune [Return to the Moon] rather than the correct Autour de la Lune [Around the Moon, 1869].)

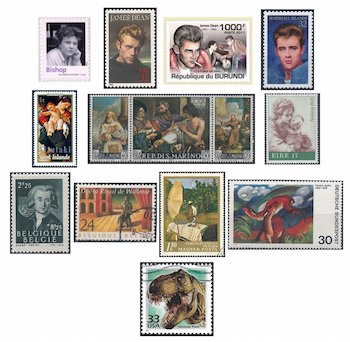

American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911 – October 6, 1979) has long been a central interest of Boston poet and critic Lloyd Schwartz. Both won the Pulitzer Prize, Bishop for poetry (1956) and Schwartz for criticism (1994). Unlike Brooklyn native Schwartz, though, Elizabeth Bishop was born here in Massachusetts, in Worcester. She lived for a time with her grandparents on Nova Scotia before returning to the Bay State (Revere and Cliftondale). An alumna of Vassar, where she co-founded the magazine Con Spirito and met her longtime friend (and poetic influence) Marianne Moore, Bishop also knew Robert Lowell and traveled widely in later years. These aspects of her life have very recently inspired no fewer than three (!) works in different genres: Michael Sledge’s 2010 novel The More I Owe You, about Bishop’s time in Brazil with Lota de Macedo Soares; a Brazilian film on the same topic, Flores Raras (Englished as Reaching for the Moon, 2013); and Sarah Ruhl’s play Dear Elizabeth (performed at Yale in 2012), about Bishop’s friendship with Lowell. As for Lloyd Schwartz’s work, see Elizabeth Bishop and Her Art, cowritten with Sybil P. Estess (1983), and Poems, Prose and Letters, coedited with Robert Giroux (2008).

James Byron Dean, born on this day in 1931, was only 24 when he died in a car crash on September 30, 1955, but made a worldwide impact from his persona, his slouch, and his performances in Rebel Without a Cause and East of Eden (both 1955) and Giant (1956), two of which earned him posthumous Academy Award nominations.

The Italian Baroque painter known as Guercino was born Giovanni Francesco Barbieri on this date in 1591. His hometown was a village situated between Bologna and Ferrara, and his career was concentrated in the former city and in Rome. The sobriquet “Guercino” (Italian for “squinter”) derives from his strabismus. A noble of the Bentivoglio family recommended him to Pope Gregory XV, who was also a Bolognese, and Guercino stayed in Rome from 1621 to 1623 (when Gregory died), producing much work before returning north, where he eventually succeeded Guido Reni as Bologna’s principal painter. He grew rich and died on December 22, 1666. Seen here are his Virgin of the Swallows on a 1972 Christmas stamp from the Cook Islands; a triptych from San Marino showing The Return of the Prodigal Son with Saints Marinus and Francis on either side; and one of Guercino’s many drawings reproduced on an Irish stamp of 1978.

This is also the birthday of Belgian composer André Grétry (8 February 1741 – 24 September 1813), who was born in Liège. Although his family was poor, he took music lessons and was able, at the age of eighteen, to compose a mass dedicated to the canons of the Liège Cathedral, one of whom paid for Grétry’s continued tuition in Rome. In 1767 Grétry arrived at Paris, where his first French opera was a hit, so he stayed and wrote fifty more. Despite losing much of his property in the Revolution, he was amply recognized by succeeding governments, and Napoleon even awarded him the Légion d’Honneur and a pension. In 1842, the city of Liège put up a statue of him (see the more recent of the two stamps). His heart is lodged within! (The other remains are at Père Lachaise.)

We turn now to two contemporaneous painters, both active at Munich around the turn of the 19th century, first the Hungarian Károly Ferenczy (KAH-roy FEH-rent-see, 1862 – March 18, 1917). He was born to a Jewish family in Vienna and earned a degree in law before being persuaded by his future wife, Olga Fialka, also a painter, to take up the brush. He traveled in Italy to experience the masters and furthered his studies in Paris. He and Olga, now married with three children, lived in Munich from 1893 to 1896, where he met Simon Hollósy, with whom they founded an artists’ colony at Nagybánya (now Baia Mare, Romania), a fount of study for many Hungarian artists. Just over five years ago, a substantive retrospective of Ferenczy’s art was held by the Hungarian National Gallery, the first major exhibition of his work in nearly a hundred years. The stamp of 1967 shows Ferenczy’s lovely, sun-drenched October (1903).

Ferenczy’s younger contemporary Franz Marc (1880 – March 4, 1916) was one of the founders of the arts journal Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in 1911. Marc was born in Munich to a German landscape painter and attended the Munich Academy of Fine Arts just a few years after Ferenczy. Travelling to France, he met Sarah Bernhardt and was taken with the work of van Gogh. Another strong influence, some years later, would be Robert Delaunay, whom Marc met in 1912. His early (emphasize early) experience in World War I was much more agreeable than was the case for millions of others: after being drafted as a cavalryman, he made use of his art in military camouflage! This took the form of canvas covers used to disguise artillery from enemy reconnaissance aircraft, and Marc delighted in using pointillist techniques in a series of nine such canvases in which he adopted styles “from Manet to Kandinsky.” But this pleasant diversion ended when Marc was killed during the Battle of Verdun in 1916. Ironically, he had just been recognized by government policy as a worthy artist who should be removed from harm’s way, but orders failed to reach him in time. The 1974 German stamp reproduces his Red Deer (1912). Marc also worked as a printmaker.

There is no stamp devoted to film composer and former Boston Pops conductor John Williams yet, but he, like Liberace, can cry all the way to the bank. One tenuous connection can be made with a stamp that comes from one of the sheets looking back on highlights from the decades of the 20th century: from the 1990s, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, for which, of course, Williams wrote the brilliantly effective music. John Williams turns 85 (!) today.

Hard to believe, maybe, but it appears that there are no stamps to commemorate the great art critic John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900), nor is there one for the American author Kate Chopin (1850 – August 22, 1904).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.