The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 5

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

Top of the line today is the sublime Swedish tenor Jussi Bjoerling, our other birthday subjects being two more Scandinavians, violinist Ole Bull and poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg, German painter Carl Spitzweg, French woman of letters the Marquise de Sévigné, highly gifted Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz, and Azerbaijani composer Gara Garayev (who may very well also be highly gifted, but I’ve never heard a note of his music). It’s also the death date of Renaissance Italian painter Giovanni Battista Moroni, the 165th anniversary of the opening to the public of the magnificent and gigantic Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and the 130th anniversary of the première of Verdi’s Otello.

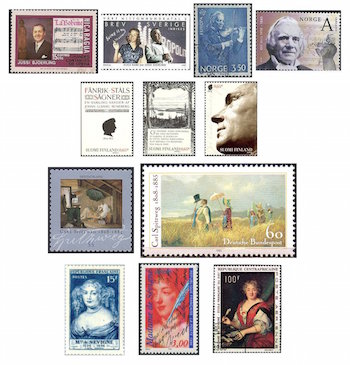

Jussi Bjoerling had one of the most beautiful tenor voices. Though born on February 5, 1911, he himself believed all his life that he had been born on the 2nd. From the age of four to his mid-teens he sang with his family quartet, which toured not only Scandinavia, but also the United States and even made some recordings. His professional debut took place in Stockholm in 1930, and just seven years later he gave a concert recital at Carnegie Hall. His Met debut followed the year after, and he remained a principal there through the 1950s. He performed on television in 1956 with Renata Tebaldi, whose birthday we just celebrated the other day. He suffered a heart attack on March 15, 1960, and sang in La bohème the same night! (This was at Covent Garden.) He died six months later, aged only 49, on September 9th. Though he left us many superb recordings, Victoria de los Angeles asserted that none of them reveals the full quality of his tone. The stamp at upper left comes from an expansive set of Nicaraguan (!) issues of 1975 celebrating opera stars. In the more recent Swedish one at right, he is seen with jazz singer Alice Babs (1924 – 2014), for whom Duke Ellington wrote his second and third Sacred Concerts.

From neighboring Norway comes Ole Bull (1810 – 17 August 1880), whose skill on the violin was such that he played in the orchestra of the theater of his native Bergen at the age of nine! But after this auspicious beginning, he failed his university examinations and bummed around Europe for a while, at one point sharing rooms with Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst, another great violin virtuoso of the day. With time, however, Bull’s concertizing made him very famous and very rich, enabling him to amass a collection of magnificent instruments by such makers as Amati, Guarneri, and Stradivari. He purchased an 11,000 acre plot in Pennsylvania in 1852, where he founded a colony called New Norway, a small part of which today forms the Ole Bull State Park. A statue was erected there in 2002. He also bought a home in Maine in 1871 and an island in Norway the next year. He was related by marriage to Edvard Grieg, though they didn’t meet until Grieg was fifteen. Bull was admired by Schumann and was a friend of Liszt. As a composer, he wrote many works for his own instrument, including two concertos, as well as other pieces.

We remain in Scandinavia for the poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804 – 6 May 1877), whose works have been a favorite source for Scandinavian composers. Although born in Jakobstad (Pietarsaari) in Finland and regarded as the national poet of that country, he wrote his poems in Swedish. His best known work is the epic “The Tales of Ensign Stål” (1848-60), from which the first poem, “Vårt land” (“Our Land” or “Maamme” in Finnish), became the unofficial national anthem of Finland, with music by Fredrik Pacius. Grieg, Sibelius, and Stenhammar (whose birthday is the day after tomorrow) are among the composers who have set Runeberg’s words. There is a Finnish national holiday, Runeberg Day (today, 5 February), a feature of which is a confection called Runeberg Torte (Finnish: Runebergintorttu; Swedish: Runebergstårta).

Carl Spitzweg (1808 – September 23, 1885) is, I suppose, much better known by name in his native Germany than elsewhere, but his delightful paintings will surely be familiar. (One could hardly expect somebody born in a town with the charming name of Unterpfaffenhofen to be other than delightful.) Like yesterday’s Georg Trakl, Spitzweg studied to become a pharmacist, but was drawn to a more personalized form of expression. He took up painting as a means of passing the time while recovering from an illness and was able to pursue his gift after receiving an inheritance when he was 25. As an artist he was entirely self-taught, wisely beginning with careful study of the Old (particularly Flemish) Masters. His first public work came in the form of contributions to satiric magazines, which perhaps set him on the path to the gently humorous paintings for which he is so fondly regarded. One of these is The Poor Poet of 1837, while the sunny Sunday Stroll (1850) pokes a little fun only in the gentlemen’s improvised umbrella. These appear on German stamps of 2006 and 1985 respectively. For closer views of these and other Spitzweg pieces, see.

The witty and vibrant letters of Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, Marquise de Sévigné (1626 – 17 April 1696) have afforded her a secure place in French literature. Her letters, most of them written to her daughter over a thirty-year span, were so diverting that copies were made and circulated, so that Mme de Sévigné after a point was well aware that any of her future correspondence could become public and composed accordingly. Three private publications appeared in 1725 and 1726, and the marquise’s granddaughter authorized a volume of 614 letters in the 1730s and 772 more in 1754, though many of these are of doubtful authenticity. As for their impact, the letters of Mme de Sévigné feature prominently in Proust and inspired a number of films, such as Sacha Guitry’s Si Versailles m’était conté… (1954) and, much more recently, Marta Balletbo-Coll’s Sévigné (2005). Born in Paris to an old family from Burgundy and orphaned at seven, Marie de Rabutin-Chantal married the Marquis de Sévigné in 1644, but he was killed in a duel in 1651. Mme de Sévigné never remarried.

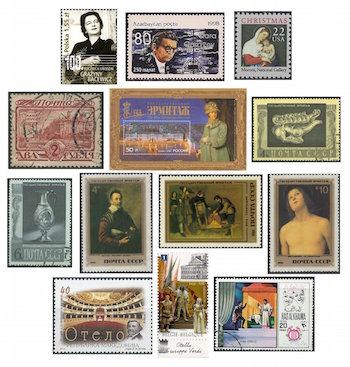

Grażyna Bacewicz (grah-ZHEE-na baht-SEH-vitch; 5 February 1909 – 17 January 1969) was also a violinist, but is perhaps more remembered for her remarkable compositions. Born in Łódź to a composer father, she was given a stipend by no less a figure than Paderewski so that she could study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger; later she returned to Paris for lessons with the violinist Carl Flesch. She was principal violin with the Polish Radio Orchestra under Grzegorz Fitelberg in the mid-30s, at a time when women very rarely held such positions. During the war Bacewicz lived in Warsaw but was able to flee to Lublin before the Uprising. She devoted herself to composition after a debilitating automobile accident in 1954. She wrote seven symphonies, seven violin concertos, and seven string quartets, the last of which, on an old Musical Heritage Society LP, was, along with her award-winning Music for Strings, Trumpets, and Percussion, my introduction to her music. There are many other works, and Bacewicz also wrote novels and short stories.

There are variant spellings for the name of Azerbaijani composer Gara Abulfaz oghlu Garayev (1918 – May 13, 1982): Qara Qarayev or, Russianized, Kara Abulfazovich Karayev. Born in Baku, Garayev led an expedition in 1937 to study folk music of the region. After his graduation from the Moscow Conservatory, he studied composition with Shostakovich during and just after World War II. Garayev held a number of important academic and administrative positions. He wrote over a hundred scores, including Seven Beauties (1952), considered the first Azerbaijani ballet, and music in most other genres. For his tragic 1958 ballet, Path of Thunder, he used African folk sources, much adapted, for the story, set in Apartheid South Africa. Rodion Shchedrin, who traveled with Garayev to the United States, was surprised and impressed by his colleague’s perceptive understanding of various types of jazz.

February 5 is the day in 1579 on which Giovanni Battista Moroni died. His reputation as one of the masters of sixteenth-century portrait painting cannot, alas, be illustrated here, as the only Moroni stamp I could locate is a US (!) Christmas stamp of 1987. Even that is but a detail of a larger work, A Gentleman in Adoration before the Madonna (for the complete painting, see). Born around 1520/24 to an architect father, Moroni apprenticed in the studio of Alessandro Bonvicino in Brescia, where Moroni established himself as a portrait painter. He was active there and in Bergamo for only a few years, however, before retiring to his nearby home town of Albino. Moroni also produced a smaller body of religious works. One of the best collections of his art can be seen in London’s National Gallery.

Speaking of magnificent collections, we turn to the The New Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, which opened to the public on this date in 1852, though the collection originated with Catherine the Great a century earlier (1764). The Hermitage is thus one of the oldest museums in the world, but it is decidedly also one of the largest, with over three million pieces (of which fully a third is made up of numismatic items). As for the sheer number of paintings, the Hermitage is without peer. There are six buildings in the complex, of which one, the Winter Palace, can be seen in an old prerevolutionary Russian stamp of 1913. Next to that is a lovely sheet issued more than a century later (2014) showing the entire complex and its progenitor Queen Catherine. Over the years the USSR put out a great many stamp sets sharing images of dozens of the items in the museums. From these I selected a few that depict works either by anonymous artists or by those whose dates of birth and death remain unknown to us, and who might thus otherwise go unrepresented in these pages. First is a Scythian golden stag figure from the 6th century BC, then in the next row, a 5th-century (AD) Persian silver jug. Next comes Portrait of an Actor (c. 1621–22) by Domenico Fetti, The Grinder by Spanish painter Antonio de Puga (1602 – 1648), and Perugino’s St. Sebastian (1493–94),. I remember watching an expansive series about the Hermitage on DVD, and I see that there’s a quite new (2014) BBC documentary called Hermitage Revealed (2014), which deals less with the collection than with the history.

Finally for today, Verdi’s Otello had its première in Milan on 5 February 1887. Stamps from Macedonia, Belgium, and Ras al Khaima specifically cite the opera.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.