Concert Review: Musicians from Marlboro Shine at the Gardner Museum

Tenor Nicholas Phan’s performance will surely be among the finest I’ll hear in the year to come.

By Susan Miron

Every year Musicians from Marlboro, the touring branch of the esteemed summer festival in Vermont, shows off its goods at Boston’s Gardner Museum. This time around brought a special treat: two works by Beethoven and Vaughan Williams that featured the extraordinary young tenor, Nicholas Phan.

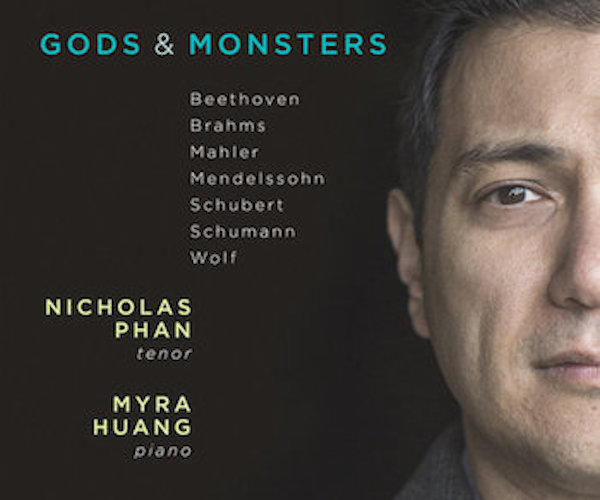

I first heard Phan several years ago on the Debut Series in The Boston Celebrity Series, then as Papageno in Mozart’s Magic Flute with Boston Baroque. I have several of his CDs, and I have been repeatedly awed and transported by his voice, stage presence, and charisma. Gods and Monsters, his latest CD, was released a few weeks ago. Phan is on the way to becoming a national treasure.

The strings, violinists Michelle Ross & Carmit Zori, violist Rebecca Albers, and cellist Alice Yoo, opened the program with Haydn’s String Quartet in D Major, Op. 76, No. 5, Hob. III:79 (1797). It was lovely seeing and hearing an all-women string quartet, particularly a day after the inspiring Women’s March. Despite being a pick-up group, they played this quartet elegantly. I had somehow, foolishly, overlooked Haydn for many decades. When I finally began to really listen to him — especially the string quartets and piano sonatas — I was overcome with regret. I have slowly been catching up, and loving it.

The String Quartet in D Major is a delight, and this quartet played it with charm. I was sitting in the First Balcony at the Calderwood Hall; customarily, reviewers have seats below, on the venue’s first floor. The location made a huge difference. Throughout the program it was difficult to hear the cello. Was it the glass barrier in front of me? I kept straining to hear the instrument. But it was hopeless, so balances were off in all four pieces. A critic who sat downstairs had no complaints about the cellist’s sound; I will not mention it again, except to say that the issues probably reflect the hall’s rather problematic acoustics.

For the Haydn, Michelle Ross played first violin and Carmit Zori played second. Marlboro prides itself on mixing up established, well-known musicians with, as the Gardner’s PR proclaims, “some of classical music’s hottest emerging stars.” Zori is a world-class musician; she won three of classical music’s biggest prizes decades ago. I believe that I’ve heard her on other Marlboro tours. She is a strong, expressive player. Ross played the first violin part with considerable beauty and flair. The excellent violist was Rebecca Albers, who plays Assistant Principal Viola in the Minnesota Orchestra.

The program’s annotator described the Haydn as a “maverick quartet.” Its first movement is certainly unusual — its form invites free variations and its character is rhapsodic. The second, slow movement, known as the “starry sky” adagio, is in the very unusual key of F# Major. It is lyrical and dramatic. The last movement is a real hippity-hop Haydn rondo. A good concert opener.

For the five Beethoven folksongs, ”Irish Lieder,” Ross and cellist Yoo were joined by the distinguished pianist Lydia Brown. Beethoven’s folk song settings are easily the most obscure and least appreciated works in his considerable output. Ironically, Beethoven wrote far more of these than any other type of composition; he composed an astounding 179 folk song arrangements, spanning a period of eleven years from 1809 to 1820.

Curiously, these folk song settings are almost entirely in English and consist mainly of Scottish, Welsh, and Irish songs. This is particularly surprising given that Beethoven never visited the British Isles during his lifetime and had no obvious connection with Britain. The reason why this association exists lies with the composer’s rocky relationship with a Scotsman, George Thomson of Edinburgh (1757-1851). There was a movement in Scotland at the time to collect folk songs; the most notable collections dated back to the early eighteenth century. Thomson, a civil servant by profession, came on this scene relatively late (in the 1790s) but with the aim to make his collection surpass all previous ones in scope and quality. A spellbinding storyteller, Phan sang these songs wonderfully, with lots of personality and a voice one could listen to all day. The beautiful diction, perfect pitch, expressiveness, and grace that he exhibited here were on display again in his rendition of Ralph Vaughan William’s song cycle “On Wenlock’s Edge.”

Vaughan Williams quintessentially British “On Wenlock’s Edge” was originally composed for tenor, string quartet, and piano in 1909. Williams reworked it for tenor and orchestra between 1918 and 1924. He chose six poems from A. E. Houseman’s collection A Shropshire Lad for the texts. I have several recordings of this memorable cycle; none of these performances are as captivating as Phan’s was on Sunday. Lydia Brown played the often harp-like piano part extremely well. This performance will surely be among the finest I’ll hear in the year to come.

Finally, the quartet regrouped for Beethoven’s relatively easy-to-play-for-a-group-which-has-little-practice time (but beloved) String Quartet in C Major, Op. 59 No. 3, “Razumovsky” (1805), this time with Zori as first violin and Ross as a superb second violinist. In truth, I would have been just as happy to have the concert end with the drama, pathos, and passion of Vaughan Williams.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 20 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. She is part of the Celtic harp and storytelling duo A Bard’s Feast with renowned storyteller Norah Dooley and, until recently, played the Celtic harp at the Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital.