Jazz Review: Sheila Jordan with the Yoko Miwa Trio at Thelonious Monkfish

Sheila Jordan, to the club crowd in Central Square: “What do I care? I’m still alive.”

Sheila Jordan – irrepressible, and still enjoying life. Photo: sheilajordanjazz.com.

By Steve Elman

[Disclosure: Thelonious Monkfish graciously provided a courtesy dinner to me and my wife on the evening of the performance.]

Of the seven great jazz singers of the bebop generation, there are now only two. The eldest is Jon Hendricks (the paradigm of “ageless ebullience,” in Nate Chinen’s phrase), who celebrated his 95th birthday in August this year. The other, second-youngest of the bunch, is Sheila Jordan, who visited Cambridge for a gig with Yoko Miwa’s trio in early December, just a few weeks after her 88th birthday.

All the others are gone: Carmen McRae, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Mose Allison (who died just four weeks ago), and Betty Carter. For the jazz lover, having heard any of these seven perform in person is a near-sacred memory burnished by the passage of time.

That fact alone made Sheila Jordan’s December 2 club date in Cambridge one to savor and one to remember, but her inexhaustible joie de vivre and her enthusiasm for working with a trio of much younger musicians made it extra special.

Jordan’s solution to the “jazz singing” problem is as distinctive as the solution devised by each of her peers. Hendricks made his rep on vocalese, the setting of words to tunes and improvisations by jazz instrumentalists, and all of his work is marked by infectious cleverness. McRae was a consummate song interpreter whose voice always had the inflections of jazz, even when she stayed close to the melody. Vaughan’s incomparable instrument allowed her to engage in glorious scat improvisations and diva-dramatic balladry with equal skill. Washington turned anything she sang into soulful, sexy blues, and listening to her made you feel naughty and nice at the same time. Allison’s great gift was cool, majestic irony, which he perfected in the writing of his own songs and in their definitive performances. Carter colored every word she sang with incomparable originality, using the very bones of her head and neck as vocal modifiers, and she was one of the strongest personalities ever to lead a jazz band, absolutely sure of herself as a writer and improviser.

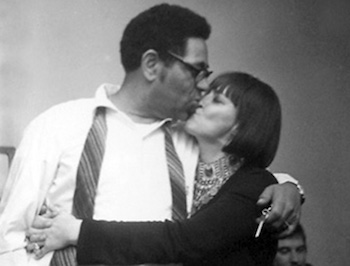

Two bebop masters – Sheila Jordan and Dizzy Gillespie. Photo: sheilajordanjazz.com.

No simple phrase can summarize what Sheila Jordan does, because her work is much more personal than that of her contemporaries. She discovered how to be herself through song, and with every passing year she has found greater depth in that approach. Her sung monologues – shards of her biography that she turns into spontaneous music – came into her repertoire more than twenty years ago, and those moments in each set are powerfully intimate. She improvises song lines about her hardscrabble childhood, her youth in Detroit, her awakening to bebop, her short marriage to pianist Duke Jordan, her raising a child alone, her long wait for recognition, her pleasure in the company of people who listen, and her joy in knowing that “My dream has come true.” But that’s just the most obvious example of her self-expression. She once told me that she could only sing a song if the lyric was true for her, which is why, for example, she has never sung “Laura,” a tune that she thinks can only be appropriate for a man or a gay woman, and why the ballads that she does choose to sing are so deeply touching. When she has written vocalese a la Jon Hendricks, the words aren’t hip fables or snappy anecdotes; instead, they tell of her interactions with or reactions to the musicians who inspired her. Sometimes she changes a written lyric into one that’s more meaningful to her; for example, at Thelonious Monkfish, instead of singing “Look for the silver lining,” she sang, “Look for your silver lining,” and turned the song into advice from an old hand at living.

All of these elements are rooted in her original identity as a bebopper. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, and all the other first-gen boppers are so idolized today that it’s easy to forget how much sheer joy they took in making groundbreaking music – as Parker said, “trying to play clean and looking for the pretty notes.” Jordan knows that joy first-hand, and she never lets you forget it.

Jordan’s performances in recent decades have tended to be in concert venues or in premier clubs, like her visit to the Regattabar in November 2011 (reviewed for the Fuse). Audiences usually are rapt and respectful, as they were for the most part in the “Jazz Baroness” music room of Thelonious Monkfish. However, the Cambridge gig threw back a bit to ones Jordan probably last did in the 1950s, because the other half of Thelonious Monkfish is a dining room – bar, and I’m willing to bet that not a single one of those noisy diners and drinkers had even half a notion of the eminence on stage just a few feet away. When she realized that she was going have to compete with them to be heard, Jordan observed with a smile, “Never get too sure of yourself.”

Those who were actually listening got a wonderful first set, mostly standards, capped with some bright original material. “How Deep Is the Ocean” demonstrated her undiminished harmonic ingenuity. “If I Had You” offered a sharp scat solo. She sang an alternate melody, almost a complete rewrite, on “All or Nothing at All.” She looked back to Hoagy Carmichael’s “Baltimore Oriole,” a tune she’s been singing since her LP debut in 1962, without a trace of boredom, and with an even deeper empathy for the poor bird jilted by the eponymous oriole. Ray Noble’s “The Touch of Your Lips” was a nice dip into neglected repertoire, and Jimmy Webb’s “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress” was a deeply moving ballad interpretation. Bebop came front and center in a medley of her ode to Parker, “The Bird,” and his “Quasimodo,” a contrafact of the Gershwins’ “Embraceable You,” decorated with Jordan’s original lyric. Her “Workshop Blues” gave the whole band a chance to shine before she introduced the closer, “Look for the Silver Lining,” with this: “Everybody has a dream. My dream has come true. If you have a dream, don’t give up.”

Pianist Yoko Miwa — Plenty of style, and plenty of technique, too. Photo: Yokomiwa.com

Wrapping the set, Jordan noted that this was the first live performance she has done with this particular trio (though she has worked previously with pianist Yoko Miwa). Bassist Brad Barrett had a prominent role throughout, and his work (both arco and pizzicato) fit Jordan’s voice pleasurably. Drummer Scott Goulding had fewer spots to himself, but his accompaniment was outstanding nonetheless. Goulding, who assists Thelonious Monkfish’s owner Jamme Chantler in the music programming, deserves a special additional nod for his help in bringing Jordan to Boston once again.

Final words, but no less enthusiasm, for pianist Miwa: She has a firmly original style, rooted in classical training but demonstrating respect for Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Dave Brubeck, Chick Corea, Jaki Byard, and even locked-hands master Milt Buckner. She never failed to turn a clever phrase in her solos, and she backed Jordan’s singing with just the right amount of personal comment. When she had a tune to herself, she chose admirably well – Charles Mingus’s “Boogie Stop Shuffle” is a challenging composition for a pianist to carry off without a team of horn players, since it has a driving ostinato bass figure topped by a complex melody line. Miwa dug into it as if she had written it.

Sheila Jordan and Yoko Miwa gave us a fearlessly musical evening, one that made a listener glad to be a jazz fan, and glad to be alive. May we Beantowners not have to wait long for another like it.

More:

Set list for first set by Sheila Jordan with the Yoko Miwa Trio at Thelonious Monkfish, December 2, 2016

1. How Deep Is the Ocean (Irving Berlin)

2. If I Had You (Irving King / Ted Shapiro)

3. All or Nothing at All (Arthur Altman / Jack Lawrence)

4. Baltimore Oriole (Hoagy Carmichael)

5. The Touch of Your Lips (Ray Noble)

6. Boogie Stop Shuffle (Charles Mingus)

7. The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (Jimmy Webb)

8. The Bird (Sheila Jordan) / Quasimodo (Charlie Parker; lyrics by Jordan)

[contrafact of “Embraceable You” (George Gershwin / Ira Gershwin)]

9. Workshop Blues (Jordan)

10. Look for the Silver Lining (Jerome Kern / Buddy De Sylva)

Jordan’s life story is ably told in her 2014 biography, Jazz Child: A Portrait of Sheila Jordan, written by Ellen Johnson.

Yoko Miwa has recorded six CDs: In the Mist of Time (Tokuma, 2000); Fadeless Flower (Polystar, 2002); Canopy of Stars (Polystar, 2004); The Day We Said Goodbye(Sunshine Digital, 2006); Live at Scullers (Jazz Cat Amnesty, 2011); and Act Naturally (JVC Victor Entertainment, 2012).

Under Jamme Chantler’s leadership, Thelonious Monkfish (524 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge) has been programming jazz since the restaurant acquired the neighboring space, formerly a Central Square clothing store, in late 2015. Dominique Eade, Tim Ray, Lynn Jolicoeur, and Eula Lawrence are among the top-notch artists who’ve worked in the Jazz Baroness Room. Yoko Miwa plays there regularly. Current music listings for the restaurant may be found here.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.