Film Preview: Busby Berkeley’s Babylon at the HFA

A 30-film series dedicated to Busby Berkeley, Hollywood’s architect of mind-blowing musical production numbers.

Busby Berkeley Babylon, a film series at the Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, MA, December 9 through January 23, 2017.

A scene from “Gold Diggers of 1933”. Directed by Mervyn LeRoy. Shown at center: Ruby Keeler.

By Betsy Sherman

Busby Berkeley Babylon is the Harvard Film Archive’s gift for the holiday season and new year. The 30-film series dedicated to Hollywood’s architect of mind-blowing musical production numbers begins on Friday, December 9 and runs through January 23. It’s a showcase not only for Berkeley’s emblematic classics made for Warner Bros., but also for his earlier Eddie Cantor vehicles, works for MGM including the Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland series (“Hey kids, let’s put on a show!”) and a host of rarities from the early days of sound films to the 1950s. Consequently, it’s a chance to hear a wealth of songs by Tin Pan Alley’s greatest tunesmiths.

The HFA did a more modest Berkeley series 11 years ago; this year’s model is beefed up with offerings such as Night World (a melodrama featuring Boris Karloff, with a Berkeley-staged musical number), Wonder Bar, and They Made Me a Criminal (a non-musical directed by Berkeley, starring John Garfield). There will definitely be a screening of that old favorite The Gang’s All Here, which was a last-minute cancelation in the previous series. Attendees can see the man himself interviewed in a 1971 installment of the long-running French series Filmmakers of our Time. Moreover, the series includes the recent digital restoration of Universal’s early talkie King of Jazz, an all-star revue starring Paul Whiteman and his big band. Berkeley had nothing to do with this film; it is included as an example of the baby steps taken in the genre before Berkeley made his big leaps of stylistic innovation. The vast majority of the movies will be shown on 35mm film (except for digital showings of the documentary, King of Jazz and the first of two screenings of 42nd Street, and one film will be 16mm).

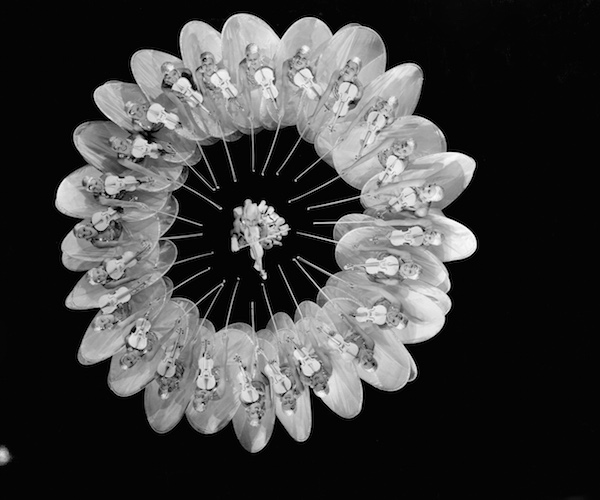

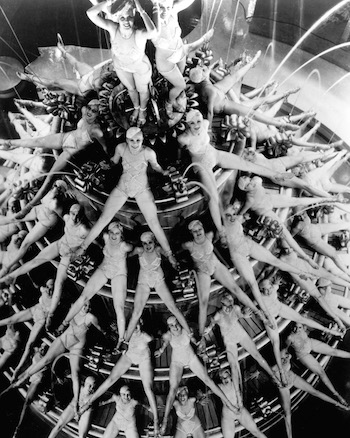

Berkeley, the son of theater folk, got his formative training organizing military drills while serving in Europe during World War I. The idea of a group working in concert to form something larger than—and often different in meaning from—the sum of its parts, fairly defines the term “Berkeleyesque.” He transformed dozens of chorus girls into kaleidoscope patterns filmed by an overhead camera, had chorines playing luminescent violins assemble in the form of one giant violin, and had dancers hold up placards that formed portraits of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his NRA (National Recovery Administration) eagle.

Whereas Berkeley achieved the stature of director in both theater and film, he started off in each medium as a “dance director” (not to be confused with choreographer). In Hollywood, the bulk of his director credits came in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Sadly, his thorny personal problems, plus an identification with a bygone era of musical films, made the studios reluctant to give him the directorial reins and he was again relegated to only staging musical numbers. The recent biography Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley, relates his rise and fall, with author Jeffrey Spivak using Berkeley’s unpublished memoir as one of his sources.

The Berkeley era began with the 1933 42nd Street, the landmark backstage musical that opens the series. While the subsequent Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade hold up better as snappy entertainment, 42nd Street (directed by Lloyd Bacon) has some potent forces going for it. It has the irresistible rise of tap dancer Ruby Keeler from chorus girl to leading lady after glamorous Bebe Daniels breaks her leg (“Sawyer, you’re going out a youngster, but you’ve got to come back a star!”). It has the aesthetic punch of numbers that unfold with an expansiveness that’s at once absurd—since they’re supposed to take place on a theater stage—and marvelously fantastical. They feature scantily clad dames who smile invitingly as the camera glides in between their gorgeous gams (Berkeley’s eroticized vision in part motivated the Production Code crackdown of 1934).

The film also gave Warners, then a liberal, pro-Democrat studio, another venue in which to comment upon Depression-era ills. Production chief Darryl Zanuck called 42nd Street a musical “exposé … which dramatically endeavors to lift the curtain and reveal the strenuous, heart-breaking efforts of a well-known Broadway producer to stage a musical in this year of depression (sic) …”

The follow-up Gold Diggers of 1933 was directed by Mervyn LeRoy, maker of the ripped-from-the-headlines dramas Little Caesar and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. Berkeley helped LeRoy put over a social statement in Gold Diggers’ opening and closing numbers. During the witty “We’re in the Money,” in which chorines’ strategic areas are covered by large coins, the sheriff’s men ironically shut down the production for nonpayment of bills. The finale “My Forgotten Man” is an alternately poignant and rousing tableau about now-unemployed World War I veterans (many of whom had marched on Washington in protest during the summer of 1932).

A scene from “42nd Street” (1933) aka Forty-Second Street, Directed by Lloyd Bacon, Shown center: Ruby Keeler.

These pre-Code backstage comedies (and the fairly racy 1934 Dames) have a special snap, with spicy dialogue delivered expertly by Warners’ wonderful character actors. Supporting Keeler and Dick Powell as the films’ unsullied sweethearts were the cynical showgirls, Joan Blondell, Una Merkel, Ginger Rogers, and Aline MacMahon. Their “marks” were most often man-child Hugh Herbert and Guy Kibbee. James Cagney brought his bristling energy to Footlight Parade, playing a Berkeley-like director of song-and-dance “prologues” that formed part of the bill in motion picture palaces. The gangster-picture icon showed off his hoofer roots opposite Keeler in the opulent “Shanghai Lil” number, which takes place in a dive bar with adjacent opium den.

Berkeley’s art reached its height in two Warners numbers, one playfully romantic, the other dark and weird: “I Only Have Eyes for You” (Dames) features dizzying multiplications of Keeler’s face as Powell croons the song; the 14-minute “Lullaby of Broadway” (Gold Diggers of 1935) is a sinister drama of hedonistic excess that draws from surrealist painting.

The man born Busby Berkeley William Enos (1895-1976) transitioned from military service to a life as a theater actor and director. In 1923, he was part of the Somerville (Mass.) Theatre Stock Company. By 1925, he was a dance director on Broadway. Eddie Cantor, the peppy vaudevillian comic, asked producer Samuel Goldwyn to hire Berkeley to stage the dances in their upcoming adaptation of Whoopee! (shot in two-strip Technicolor).

Berkeley brought an irreverent attitude to the medium. When told it was the practice for four cameras to shoot a musical scene, to improve coverage, he countered that only one would be necessary—and that sense of an all-seeing single camera-eye became another fundamental of the “Berkeleyesque.” He cast a gaggle of cuties, and created a tracking shot that ran through their spread legs. It was a hit. The collaboration continued with the 1931 Palmy Days, in which Cantor runs amok in a female-staffed bakery, and the 1933 Roman Scandals. The latter, co-written by George S. Kaufman and Robert Sherwood, has some social commentary in its present-day framing sequences. Cantor suggests, in song, that a group of evicted tenants should live communally. Then his character is transported to ancient Rome. The hijinks begin with a slave auction featuring shackled beauties, nude under long blonde tresses. The plot calls for Cantor to masquerade both racially and sexually: he’s disguised as an Ethiopian eunuch in a salon where white Roman women are groomed by black women slaves (the two groups form complementary chorus lines).

A Busby Berkeley dance sequence in”Footlight Parade” Directed by Lloyd Bacon.

This is a good place to pause and acknowledge the massive insensitivity that was carried over from vaudeville into many of the Berkeley pictures. Cantor and Al Jolson, co-star of Wonder Bar, were known for their fondness for blackface, used for either comic effect or, in the case of Jolson, for pathos (for in-depth analysis of the practice, see Michael Rogin’s book Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot). The production number “Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule” in the 1934 Wonder Bar, with its egregious stereotyping of black people, is a reason why it’s rarely shown. It doesn’t only apply to films with those two stars—the Mickey & Judy pictures have minstrel-show numbers with blackface—and there aren’t just stereotypes of African-Americans. There are whites in “redface” as Native Americans, Ruby Keeler’s cringe-inducing impersonation of a Chinese accented woman in “Shanghai Lil,” and caricatures of Latin Americans. The non-Berkeley King of Jazz is a cornucopia of wrongness, starting with an opening cartoon (the first in two-strip Technicolor) showing bandleader Paul Whiteman “discovering” jazz in Africa (he has long been the subject of controversy for his appropriation of African-American music with only lip-service “gratitude”). The HFA screenings of these titles will have introductions that discuss the films in their social context.

And hell, I can’t exactly ignore the objectification of all those uncredited Berkeley Girls presented as arousal-inducing facets of an elaborate design. However, since much ink has been expended about that over the decades, I’ll bring up a pet peeve about one movie in the series. Rarely has a professional-woman character been more shabbily treated than Bette Davis in William Dieterle’s Fashions of 1934 (for which Berkeley staged a keen number featuring a whole lot of ostrich feathers). As the designer partner of William Powell and Frank McHugh in a fashion-swindling scam, she has to constantly fend off McHugh’s advances, which is supposed to be part of the fun (too bad this series doesn’t have Berkeley’s first co-directing credit, the 1933 non-musical She Had to Say Yes, which, though it couldn’t be called feminist, is a fascinating, unexpectedly frank look at sexual harassment in the workplace).

As the decade marched on and the Code came into force, the “book” sections of the Berkeley movies lost their flavor, but spectacular numbers could still be found, like “The Lady in Red” in In Caliente and “All’s Fair in Love and War” in Gold Diggers of 1937. Towards the end of the 1930s, Berkeley signed with MGM, whose slogan “More Stars Than There Are In Heaven” ran counter to his collectivist roots. His fondness for using female flesh as building blocks would be nixed by MGM boss Louis B. Mayer, whose attitude was “wholesomer than thou” (in the words of star Mickey Rooney).

Berkeley directed three-and-a-fraction pictures starring Rooney and Garland: Babes in Arms, Babes on Broadway, Strike Up the Band and Girl Crazy, from which he was fired (Norman Taurog gets co-director credit). With the hugely successful 1939 Babes in Arms, in which the children of former vaudevillians stage a homegrown musical revue, Berkeley apparently tapped into the cultural zeitgeist. With Europe at war and America confused, audiences responded to the film’s warm bath of nostalgia and flag-waving. The closing number “God’s Country” proclaims that here, “every man is his own dictator” and the squeaky clean kids sing “Drop your sabers/We’re all gonna be good neighbors.”

Garland, who found Berkeley to be abrasive and downright unnerving, appears in two more pictures in the series. In Ziegfeld Girl, she’s part of a trio of aspirants along with Hedy Lamarr and Lana Turner. In For Me and My Gal, directed by Berkeley, she and Gene Kelly do some fine dramatic, as well as musical, work in the story of a vaudeville team affected by the call-up of soldiers for World War I. Berkeley directed some fantastic set-pieces for ace tap dancer Eleanor Powell in Lady Be Good, and began an association with water ballet star Esther Williams with Million Dollar Mermaid (a stodgy film aside from the breathtaking numbers). The 1949 Take Me Out to the Ball Game, starring Kelly and Frank Sinatra, earned Berkeley his last directorial credit, and the 1951 Call Me Mister, for which he staged dances, is the last film, chronologically, in the HFA series.

Ironically, it was a little Technicolor picture that Berkeley made for Twentieth Century Fox in 1943 that had a great impact on his life decades later. The Gang’s All Here, featuring the over-the-top Carmen Miranda singing “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat” along with chorus girls wielding huge, phallic bananas, was re-discovered as a camp classic during the post-psychedelic 1970s. Concurrently, a Broadway musical Dames at Sea rendered an homage to the Keeler-Powell extravaganzas. Berkeley, plucked from obscurity at age 76, was offered a chance to direct Keeler in a Broadway revival of No, No, Nanette. He got a bit of a run-around, and only received a “production supervisor” credit, but during his last years he was fêted at film festivals around the world. It was a happy finale for a deserving, and enduring, artist.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: 42nd Street, Busby Berkeley, Busby Berkeley Babylon, MGM, film musicals