Cultural Commentary: Things Get Worse at the Boston Globe and Elsewhere — More Arts Criticism Bites the Dust

Many of today’s arts editors and reviewers embrace a lilliputian vision of arts criticism; they accept a crabbed sense of its rich possibilities.

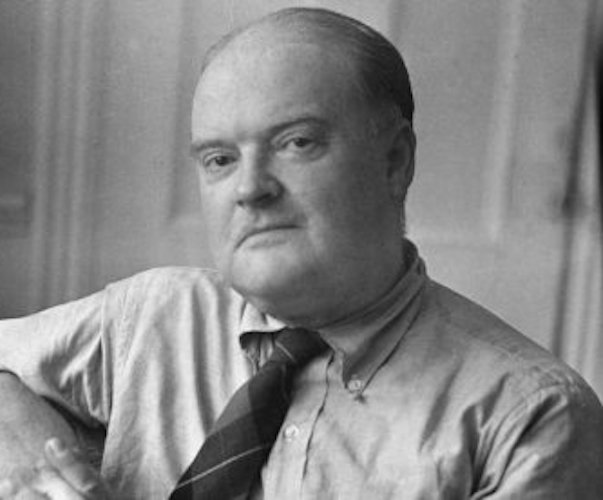

In the 1920s reviewer Edmund Wilson wrote about the critics ‘who do not exist.’ More no longer exist today, and the fade-out continues at the “New York Times” and the “Wall Street Journal.”

By Bill Marx

In his November 9th piece for Deadline Hollywood, Jeremy Gerard reports that the bottom is falling out for serious arts criticism at The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Reviewers will be fighting for their existence in the online equivalent of journalistic death cage matches: picked off in hybrid lifestyle sections, such as the Journal‘s new “Life and Arts.” And that fade-out encourages publications lower on the food chain to ditch arts criticism, if they haven’t already. Or it serves as an excuse to let reviews gently dangle over the edge of the cliff, as The Boston Globe is doing with its move to have non-profit organizations pay for arts criticism.

Even in the Big Apple, when the going gets tough in-depth arts coverage is is gone for good. Print advertising revenue is shrinking at an alarmingly fast pace (a 19% drop in the third-quarter, according to the NYTimes‘s own report; the Journal admits a 12% decline in domestic advertising). And in the hellbent competition for internet eyeballs arts reviews fall (unsurprisingly) far short of bean counter demands. Thus resources are moved from cultural coverage to places where click bait can be manufactured more easily. Of course, the reduction in writing on the arts is always framed by editors as making the section ‘better than ever.’

According to Gerard, the NYTimes‘s stand alone book section is in danger, while

According to multiple sources at the paper, the [NYTimes] Arts section is about to undergo a downsizing and refocus of coverage, which will be introduced after the New Year.

“It’s going to be a bloodbath,” another current culture staff member told Deadline, speaking anonymously — as did all of the staff members interviewed for this story because they were not authorized to speak and did not want to further jeopardize their positions.

………………..

The revamped Arts front page will have no more than three stories (there now are sometimes as many as six) anchored by an oversize photograph, according to sources who have been apprised of the changes. (Today’s Arts section is a good example of what the section will more typically look like.) Critics have been urged to stop covering events least likely to appeal to online subscribers: indie movies having brief runs in art houses; one-night-only concerts, off- and off-off-Broadway shows that aren’t star-driven, cabaret performances, and small art galleries. Many of the Times‘ contingent of freelance contributors, who provide much of that coverage, are likely to meet the same fate as the regional freelancers last summer. But even staff critics have been given the same marching orders, telling Deadline they are being pressured more frequently by editors to focus on higher-profile events.

Of course, when cultural coverage is cut it is the small and medium-sized arts organizations that suffer the most. The larger organizations have the funding muscle and tony connections (as well as the advertising/marketing/social media clout) to generate interest in their wares. It is the marginal, the innovative, the iconoclastic, the un-safe indie artists in need of attention who feel the full Darwinian fury. The actions at the NYTimes and Wall Street Journal are the culmination of a process that began in earnest during the 1990s — mainstream newspapers and magazines decided it was just fine to abdicate their responsibility (which goes back to the early 19th century) to generate thoughtful dialogue about the arts, particularly to weigh in on issues of their quality. I have written often about this development, so I won’t go into the argument again.

Gerard has been good on the decline of NYC’s arts coverage, but he hasn’t touched on how decades of increasingly anemic and dismembered arts sections has ostracized high quality, hard-hitting arts criticism. (The toothlessness of so many of today’s reviews surely plays a part in reader indifference.) Reviews have been sidelined for decades, their column inches cut back, so talented writers have understandably gone to work in more career friendly sections of the newspaper.

The result: too many of today’s arts editors and reviewers embrace a lilliputian vision of arts criticism, a crabbed sense of its possibilities. I teach a class at Boston University on writing arts criticism, and can testify that most of these wanna-be critics have not read any reviews that date earlier than 2000 — no James Agee, Andrew Sarris, Lester Bangs, Ellen Willis, Edmund Wilson, Virgil Thomson, Edgar Allan Poe, H.L. Mencken, Pauline Kael, etc. (Thanks to the Library of America, the reviews of some of our finest arts critics are available for those who want to see how first-rate criticism has been done over the past two centuries.) Don’t get me wrong — there are some very fine arts critics round and about today. But there are fewer professional editors who demand excellence and places for brilliant work to be posted — now the NYTimes and Journal will no longer provide as roomy a home.

Thus my genial skepticism about the Boston Globe‘s move to have the position of a full-time classical music critic subsidized by a trio of non-profits. According to former Globe editor Steve Smith in The Log Journal:

On Oct. 31, the Boston Globe became the epicenter of the arts-journalism world when it announced that Zoë Madonna, an award-winning classical music critic who’d been contributing to the paper as a freelance reviewer and reporter since Sept. 2015, had been engaged to a temporary full-time position that would be funded by an outside entity: specifically, a consortium of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, and the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation.

The arrangement was set-up to deal with the absence of Jeremy Eichler, the Globe‘s full-time staff classical music critic, who is leaving for a 10 month Radcliffe Fellowship. The award-winning critic Madonna will take his place; the money saved by the newspaper will help to pay for the contributions of increasingly endangered freelance arts reviewers.

On the one hand, I agree with Smith that the proof is in the pudding. If Madonna writes high quality reviews (her clips are very impressive) then the Globe‘s experiment will be justified. Still, this move is far from radical — diacritical aptly calls it a band-aid. And I wish Smith would not characterize arts reviewing as being ‘objective’ — reviews are subjective verdicts backed up by good reasons. I think what Smith means is that critics should be independent and honest; he notes how critics of the Globe‘s cozy arrangement have raised the obvious issue of conflict of interest. It is a genuine fear, but I do not share the fear of veteran Guardian theater critic Michael Billington that “the danger, in such a situation, is not that the critic will give a soft ride to her fellow beneficiaries, it is more likely that she will be unduly rigorous in order to display her independence.” London’s arts coverage is far more far more combative and energetic than Boston’s — readers take their arts and culture far more passionately there — so I would be ecstatic if Madonna was ‘rigorous’ rather than diplomatic, which is the default mode at the Globe.

Smith’s claim for the ‘revolutionary’ nature of the Globe‘s set-up neglects the editorial fuzziness produced by decades of decaying arts coverage. There are few people left with the courage and conviction to hit the barricades. It could be argued that the mainstream print media (taking its cue from lucrative Cable TV news) aren’t all that interested in encouraging vigorous criticism. Responding to the shock that greeted reports there would be severe cutbacks in freelance arts criticism, the Globe‘s arts editor, Rebecca Ostriker, did not proclaim the need for reviews. Instead, she waxed enthusiastic about running stories about the arts:

We’re looking to tell the most compelling stories that will appeal to readers in every area of the arts. We are encouraging artists, performers, and arts organizations of all kinds to share their best ideas for feature stories with us. And we will be counting on all of our terrific freelance writers to help us tell those stories.

Madonna may be a hell of a critic, but I suspect she is going to be asked to write quite a few stories. And that may be one of the strategies (agreeable to non-profit arts funders?) being tried out to ensure the diluted presence of arts criticism in newspapers: reviews will no longer be rooted in strong evaluation but morph into friendlier, hybrid forms of information/ marketing fodder. The consumer-orientated idea is to sell interest in the arts to as broad an internet readership as possible, and that means tamping down on provocative judgments.

That is what Smith and other hand-wringers about arts criticism miss: the challenge facing reviewing is partly, but not solely, about shrinking resources — though, on that front, what happens when Eichler comes back? Should the freelance critics, sans the non-profit subsidy, fear they will be out in the cold again? And, going a step further, how much (and what kind of) bang do the non-profits funding Madonna’s criticism want for their buck? Is it a stretch to suspect that their expectations may shape editorial demands in the future? Consider the opportunity: non-profits may pony up even more money next year in order to support other Globe arts critics — if they see the kind of criticism/stories worth supporting. When criticism sings for its supper, keep your eye on who calls the tune.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

A frightening state of affairs, especially for someone like me. And doubly so if the students at BU who are taking classes in arts criticism haven’t read people from pre-2000, like Bangs, Agee, Kael, or my beloved Bunny Wilson – I cheered when I saw the picture at the top of the page! I wonder if that means the fossilization process has begun…