Book Review: “Just Around Midnight” — A Revelatory Look at Race and 1960s Rock and Roll

Why did rock and roll become white? Music critic Jack Hamilton’s extraordinary new book provides a challenging answer.

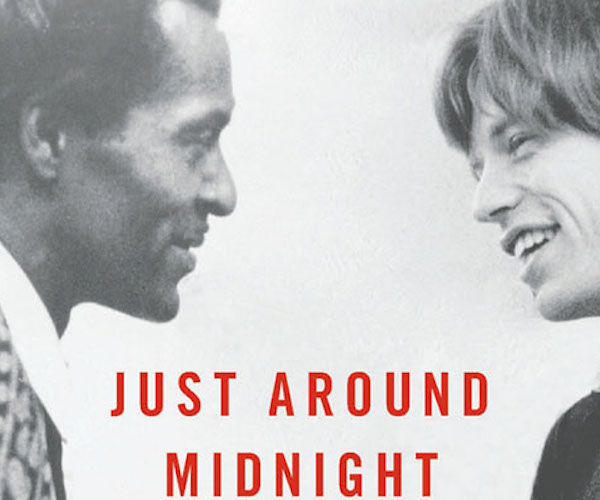

Just around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination by Jack Hamilton. Harvard University Press, 352 pages, $29.95.

By Adam Ellsworth

“If you tried to give rock and roll another name,” John Lennon said in 1972, “you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’”

What, you were expecting Elvis? Elvis may have been the King, but Berry was rock’s first triple threat. Not only could he sing and play guitar, he was also a great (make that GREAT) songwriter. So phenomenal is Berry’s music that in 1977 NASA sent a recording of his “Johnny B. Goode” into space on the Voyager spacecraft. And that’s not even his best song!

Berry was the prototype. All “serious” rock musicians of the 1960s who wrote, sang, and played their own songs were following his example from a decade earlier. But there was one major difference between Berry and his disciples: Chuck Berry was black.

“Is” black actually, as Berry is thankfully still alive. In his 89 years on Earth he’s seen rock and roll morph from “black music” played by both blacks and whites, to “white music” performed almost exclusively by Caucasians. Not that it took 89 years for this change to occur. It was already complete less than 10 years after Berry released “Johnny B. Goode.”

How this transition happened is the subject of music critic Jack Hamilton’s extraordinary new book Just around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination.

“Rock and roll became white in large part because of the stories people told themselves about it,” Hamilton writes in his Introduction, “stories that have come to structure the way we listen to an entire era of sound.”

These stories come from many sources, but most prominent is that of the rock critic. The rise of rock music as a cultural force in the 1960s also brought along the rise of the critics, and it was these commentators, Hamilton writes, that etched in stone how rock and roll was supposed to sound and look. Though their conclusions weren’t necessarily arrived at maliciously, the result was the creation of a musical history that treats pioneering figures like Berry, Little Richard, and Bo Diddley as primitives who were vital to the creation of the genre, but ultimately nothing more than heroes of the past who paved the way for ARTISTS like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. In this telling, Berry may have been John the Baptist, but Lennon was (more popular than) Jesus.

The point of all this is not to criticize the ‘60s white artists. As Hamilton makes clear throughout the book, these musicians would shout to anyone who would listen that what they were performing was heavily influenced by black music, and if their fans liked them, then they’d really love the originators. Unfortunately very few listened to these confessions, and rock history was set.

This narrative is not shocking to anyone who has thought seriously about rock and roll, though it still never hurts to repeat it. Where the book is really a mind bender though, is when Hamilton focuses on how history has treated black artists who tried to create a music that didn’t fit into the accepted “authentic” narrative that was reserved for them. In his chapter where he compares the careers of the exhaustively studied Bob Dylan and the tragically under examined Sam Cooke he discusses the differences between the latter’s live albums Live at the Copa and Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963.

“Harlem Square Club finds Cooke performing in full gospel fury, inciting the crowd to a frenzy and racking his voice to the edge of oblivion,” Hamilton writes. “Live at the Copa, on the other hand, is debonair and refined.”

It probably goes without saying that the Harlem Square Club audience was black, while the Copa crowd was white. More than half a century later, Cooke’s legend is secure and no-one would suggest he was an Uncle Tom for his “restrained” Copa performance. Still the narrative that has been agreed to is that Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963 represents the “real” “black” Cooke, while Live at the Copa is a mask he was forced to put on. As he does throughout Just around Midnight, Hamilton seriously challenges this over-simplification and focuses on Cooke’s Copa performance of Dylan’s civil rights anthem “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

“Cooke’s decision to bring ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ to the crowd at the Copa was both a politically and culturally transgressive act,” he writes. “While many in the audience surely knew the song…in mid-1964 Bob Dylan was still a liminal figure in American life, poet-troubadour to a rising New Left whose behavior and artistic persona were viewed by many as overly radical.”

In short, when it comes to musical questions of black and white, things aren’t always so black and white. There’s nothing wrong with preferring one performance over the other, but you should consider why you prefer one over the other, because both the Copa and the Harlem Square Club performances are real. Both are black. And both are Sam Cooke.

Other chapters of Just around Midnight consider the influence of Motown on the Beatles and the Beatles on Motown, the question of soul and how it was represented by African American Aretha Franklin, white southern American Janis Joplin, and white Englishwoman Dusty Springfield, and the references to violence by Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones in their music.

The look at Hendrix is particularly fascinating. Today, rock fans simply recognize him as the lone black face on the Mount Rushmore of Rock. In his time though, he was treated as an “alien” by the white rock world. Accepted perhaps, but “other.” To many blacks, he was a traitor to his race for playing what had become white music. Even some white critics, including “the Dean” himself Robert Christgau, thought he was flash over substance and “just another Uncle Tom.” As all this illustrates, by the late ‘60s, blacks were only truly accepted when they played “authentic” black music that stuck to the basics, and how authentic this music was would often be decided by whites. White musicians on the other hand were allowed as much freedom as they wanted to explore what they wanted. After all, they were artists.

Hamilton doesn’t pretend to have all the answers in Just around Midnight but he asks all the right questions. It challenges so much of what we’ve taken for granted about rock and roll history that one reading won’t do. This is a book that needs to be returned to over the years, once initial readings have had a chance to sink in and we’ve all been able to recalibrate our understanding of the music’s history. Any future book that deals with the social and racial aspects of popular music in the 20th century will have to contend with Just around Midnight. The bar has been raised.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24

Tagged: Harvard University Press, Jack Hamilton, Just Around Midnight, Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, race

The reopens a set of questions that are rarely asked and when they are, they are quickly forgotten about.

When I was a teenager, how was it that Hendrix, who was to my mind, a creative force on the same level as The Beatles, the only black artist regularly played on the local rock station? How was it that even D-list white artists were getting as much airplay as him? Why wasn’t Prince played only on the “black” station? How was it that neither the [white] rock nor the black radio stations were willing to touch Living Colour or Fishbone? (Why was the Black Rock Coalition of the 1980s even necessary — oh wait, I answered that question) When Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf recorded their psychedelic albums, why did the critics reject them?