Book Review: “My Marriage” — An Extraordinary Rediscovery

Despite the pain of inhabiting Alexander Herzog’s disintegrating world, I absolutely could not put My Marriage aside.

My Marriage by Jakob Wassermann. Translated from the German and with an introduction by Michael Hofmann. New York Review Books Classics, 288, $15.95 (paperback).

By Kai Maristed

Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks was published in 1901 by a well-to-do twenty-six-year-old on his way to lasting literary achievement and fame. Jakob Wassermann, roughly Mann’s contemporary, enjoyed considerable contemporary readership, but little of his prolific output survives in literary memory. The extraordinary exception is this short novel, re-discovered and brought into the light by the excellent translator, poet, and critic Michael Hofmann. My Marriage first saw print in Amsterdam in 1934, months after the death of its ailing and penniless sixty-year-old, black-listed German-Jewish author. Despite the authors’ dissimilar fates, the artful opening of Wassermann’s novel evokes Mann’s gimlet-eyed social observation:

She had five sisters — four older, one younger. The six Mevis girls were known all over the city. Wherever they appeared together, they were like a small army of Amazons, a sealed phalanx, from the classically beautiful Lydia to the graceful Traude. Their father and commander-in-chief, Professor Gottfried Mevis, shining beacon of the law faculty…was their Barbarossa. […] Frau Mevis, given name Alice, née Lotelott—one of the Duesseldorf Lottelotts, of Lottelott and Grunert, Consolidated Steel—had inherited a large fortune. The family, respected and envied, lived comfortably in a spacious villa.

This ironized haut bourgeois idyll is soon marred by closer acquaintance with the youngest daughter, Ganna. “Mirrors proclaimed it, the expressions and reactions of others confirmed it: she was the ugly duckling among five swans. Therefore it was her task to clear a path for herself through the five arrogant swans. […] Even as a child she had been hard to manage. […] In her tenth year, Professor Mevis took to giving her twice-weekly prophylactic beatings, to get her out of the habit of lying. A barbarous measure, which failed to achieve its purpose…”

Thus Wassermann begins the unsparing autobiographical story of his marriage: not with a conventional first encounter, but with an unprettified portrait of a defiant little girl long before he knew her. It’s a portrait that both tugs at one’s heartstrings — because who does not root for the feisty ugly duckling, pecked by swans? — and unsettles. Ganna is appealingly unruly, yes, a rebel always uncombed and late to table, clumsy, forgetful, a teller of tall tales: “Lying becomes an indispensible weapon for Ganna, like the black liquid into which the cuttlefish disappears.” But as she enters adolescence and as the older sisters make their fine matches, she becomes even more intransigent and convinced of her own superiority. She latches on to literature as the medium for her self-actualization and ambition and Nietzschean will, holding literary sessions at home from which the family is strictly excluded. Wassermann — excuse me, his alter ego, Alexander Herzog — attempts to deepen the portrait with psychoanalytic brushstrokes hinting at an erotic pull and hatred between Ganna and her exasperated father, the only person she could ever acknowledge as master.

Yet even at this point, and more so as the story moves forward, there is a fundamental ambiguity, the focus vacillating between multiple versions of Ganna: the exalted one, the pitiful one, the bad, the outright terrifying. Part of the surprising modernity of this novel (which was actually a fragment of an unfinished longer work) is the way it wrestles with shifting perceptions of identity. How can one ever truly know another person? Or know one’s self? “People couldn’t be a mirror for her, nor could the real world, it was only in books that she encountered a being like herself — so she thought — a trusting being full of earnestness and passion. […] It [was] therefore inevitable that a writer, a certifiable writer, would come to hold the meaning of the universe for Ganna, to save her from the repellent superficiality of the Mevis empire, the tarn with the five exemplary swans.”

Well, Alexander Herzog is a certifiable writer, his first novel having been a critical success that left “my grim financial situation…unaffected.” He rents a cold-water room and survives, barely, by mooching off better-heeled friends. When Ganna gets wind of his presence in Vienna she employs all her cunning and willpower to bring about an introduction, and then sends Herzog a passionately admiring missive through the pneumatique. For his part, although he found her “splendid teeth” and “charming innocent laugh” not unattractive, he was put off by her excited enthusiasms and “uncommonly small, twitchy hands displaying recurrent gestures that had something jagged and assertive about them, which she became aware of at intervals and tried to moderate.” The reader will notice those hands again, in less innocent circumstances.

Against his better judgment, Herzog succumbs to flattery. In retrospect he realizes that “from the moment I first wrote back she had acquired in perpetuity a right to be answered. And so a man gets ensnared.” Herzog isn’t quite ensnared yet, but he will be soon, on account of Ganna’s single-minded vision of their future, her devotion to his work, and the incentive of a dowry lavish enough to promise a life in which, with prudence, he could write without worrying about the rent.

An awful but appropriate title for this novel might have been The Slippery Slope. Almost from the outset, we sense the general direction in which this story is heading. And we suspect that like any object rolling downhill, it will accelerate as it goes. Part way into the novel a question began to nag at me: why do we read stories (or watch movies, for that matter) that are relentless slippery slopes, downers in the most literal sense? Where’s the pleasure in it? Is it hope against hope, that somehow the hero will break free at the last moment? (Hard, with this book. Herzog’s foreshadowing doesn’t leave much room for hope.) Is it Schadenfreude, or the ‘compared to that, my life’s not so bad’ syndrome? Or the accident rubbernecking syndrome? Drivers slowing to a crawl, mesmerized, curious, inwardly quailing yet unable to take their eyes off the carnage, wanting to take in every detail, even at the risk of causing another accident themselves.

Not to compare My Marriage to a multi-car pile-up, even though multiple lives do get sucked into the downward spiral that is the dance of Ganna and Alexander: their two children, a number of women with whom Herzog conducts torrid affairs, and finally Bettina, his later muse and comfort, as well as their son.

Beyond the usual possible motives, there are three outstanding reasons why, despite the pain of inhabiting Herzog’s disintegrating world, I absolutely could not put My Marriage aside.

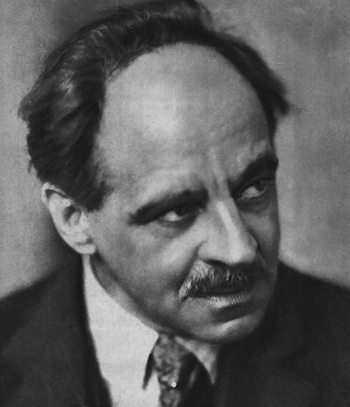

Jakob Wasserman. Photo: Wiki Commons.

First, there is the shimmering depiction of character, as expressed, classically, through behavior — acts of kindness or daring or self-delusion, decisions made and decisions avoided. Anyone who has ever lived with or even brushed up against a megalomaniac narcissist (but Wassermann is much too good to resort to such catch-bin terms) will thrill with foreboding as Ganna, both terribly harmful and cruelly harmed, ratchets up her campaigns first to mold, then to bind, and eventually to destroy her husband rather than see him taste some crumbs of peace and happiness. Her recourse to a string of lawyers with droll names of predatory birds (Stork, Pelican etc.) and great skill in extracting the last thalers from the Mevis dowry, along with Herzog’s attempts at appeasement and legal defense, feel as inexorably choreographed as the case of Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce in Bleak House.

Then there is the acute dissection of social relations — between the sexes, between the classes, the romance of friendship — at a certain point in history. History with a very small ‘h’, for while My Marriage takes place before, during, and after World War I, that inferno exists in the novel as ‘noises off-stage’ for the Viennese lucky enough to stay home (Herzog had a medical exemption). As the narrator puts it, “While the Dual Monarchy was collapsing and being torn to shreds, while Germany was wracked by revolution […] and the charnel smell wafting over from the battlefields was poisoning the cities and the influenza epidemic seemed set to mow down whatever was left of youth and life […] Ganna in her little domestic state was turning things on their heads, piling discord on discord …” What mattered day to day, for average people, was finding eggs and flour on the black market. The truth is, as Auden pointed out to us, that suffering takes place “while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.” [“Musee des Beaux Arts”]

Finally, and most tellingly, I was held by the moral complexity of Alexander Herzog’s confession. Confession, or self-justification? He veers between the two extremes, asking of himself, and the adjudicating reader, nothing less than the truth. He admires, fears, loathes, and despises his wife. And himself. He peels back the layers of his complicity. Was he Ganna’s victim from before she set eyes on him, doomed by a certain passivity and natural goodwill? Or was his crime to have married a woman he was more in awe of than in love with, and did everything hinge on that first, fatal accommodation? Did she rob him of his health, children, and creativity? Did he drive her insane? Which of them was the real monster?

In the end the reader is left juggling Herzog’s alternative, persuasive, incompatible ways of seeing, even past the final pages. And that is the real fascination of My Marriage.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other publications. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, a novel set in Berlin. Read her Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

Tagged: Jakob Wassermann, Kai Maristed, Michael Hofmann, My Marriage, New York Review Books Classic