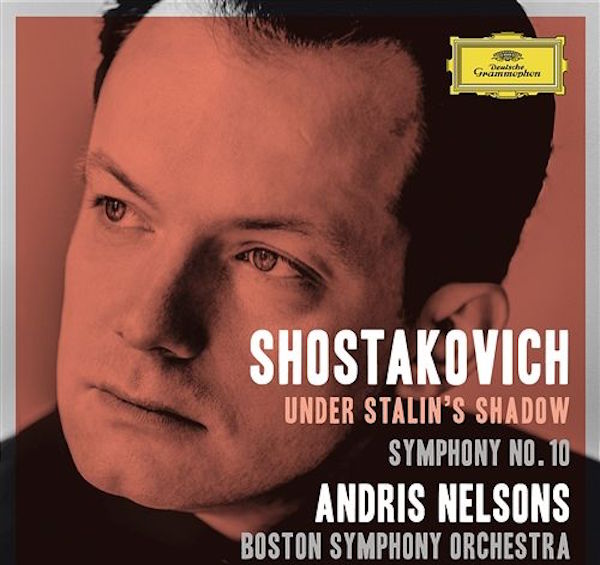

Classical CD Review: Great Performances — “Under Stalin’s Shadow,” vol. 2 (Deutsche Grammophon)

That Shostakovich left such a musical testament is, in its own way, miraculous; that it continues to speak to us with immediacy and power only reflects the enduring tragedy of the human condition.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

How does the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) follow up its Grammy Award-winning recording of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 10, the first of a (now-to-be-complete) Shostakovich symphony cycle for Deutsche Grammophon? With more of the same, it seems, much more: more music, more energy, more color and fire.

The next installment of the BSO’s series, dubbed Under Stalin’s Shadow, offers three symphonies (nos. 5, 8, and 9) plus the Suite from Shostakovich’s incidental music to Hamlet. It also reveals an orchestra increasingly comfortable and simpatico with its music director, Andris Nelsons. That last is perhaps the most satisfying takeaway for the BSO and its fan base. The chemistry between this pair has grown immensely over the last year and there’s no denying that when both sides click, sparks fly. Suffice it to say, there are plenty of fireworks here.

With the exception of the score from Hamlet (written in 1932), the music on this two-disc set closely traces the traumatic years between 1937 (the height of the Stalinist purges) and 1945 (the end of World War 2). Of these three symphonies, only the Fifth, written in response to the denunciation of Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (thought to have come from Stalin’s pen), has experienced real popular acclaim. The Eighth, composed just as the tide of war began to turn in 1943, and Ninth, premiered after it ended in 1945, both fell afoul of the Soviet regime: the former wasn’t appropriately triumphant and the latter lacked the depth and sobriety due the historical moment. While both of the last two turn up on occasion, neither is overly familiar. Indeed, the BSO’s performance of the Ninth this past October marked just the third time the orchestra’s ever played the score – and the first time since 1962.

Happily, you wouldn’t be able to tell that from this recording. Quite the contrary: this is music that seems to be very much a part of the orchestra’s DNA. As far as individual readings go, the BSO’s performances are highlighted by some staggeringly beautiful woodwind playing. This characteristic is fast becoming one of the hallmarks of Nelsons’ early relationship with the BSO and here – whether it’s William Hudgins’ limpid clarinet solos in the slow movement of the Ninth or Richard Svoboda’s jocular bassoon playing in the finale of the same, Elizabeth Rowe’s aching lyricism in the slow movement of the Fifth, or Robert Sheena’s dulcet English horn in the Eighth’s huge first movement – the playing is simply fantastic: supple, colorful, and filled with character.

In other departments there are impressive demonstrations of the same qualities. The brass shine throughout these three symphonies, whether building to the music’s great (and sometimes terrifying) zeniths or supplying sardonic commentary on the proceedings. Strings sound rich and sturdy when called for (as in the Fifth’s opening movements and the Eighth’s middle ones) but also play with remarkable delicacy and vulnerability. It’s particularly nice to get to hear Malcolm Lowe’s accounts of these scores’ many violin solos again.

On the whole, Nelsons’ approach to these symphonies is spacious and hands-off. This tack works particularly well in his conducting of some of the bigger movements. Take the opening one of the Symphony no. 8, which which is kind of like a Hitchcock movie: the music needs the combination of time in which to settle and speak and a conductor who will let it tell its story. Nelsons is the latter and he provides the former (the performance runs nearly twenty-seven minutes long); as a result, this colossal, sprawling symphonic essay, which builds to a ferocious explosion, packs an enduring dramatic wallop.

Letting the music speak can also have the effect of drawing out details and contexts that might otherwise go overlooked. For instance, one hears the Russian Orthodox-like chorales near the beginning of that Fifth’s devastating third movement in a very clear, potent way on this recording. When they’re countered, after the movement’s impassioned apex, with the desolate contrapuntal string passages that lead to its close, the whole thing takes on a deeply devotional, almost mystical quality: the anguish and pain the music expresses has rarely sounded as deeply personal and, simultaneously, all-embracing as it does here. That owes entirely to Nelsons’ interpretation and the BSO’s sensitive execution of it.

And there are similar treasures and epiphanies to be gleaned listening to each piece in turn. Throughout, the BSO plays like they care about each note in a deep, special way: these are great performances, no doubt, intense and focused, showcasing some brilliant orchestral virtuosity along the way.

That said, this set can, emotionally, be a rather grim go. The Eighth, after all, broods like nobody’s business. And the Fifth offers no easy answers: Nelsons even gets the vacuously triumphant finale to seem to scream out in genuine pain at one point, which is no mean feat. As for the witty Ninth, its façade slips time and again. The shadows are never far off, even when spirits seem to be at their highest – just listen to the menacing textures of the finale’s climax if you doubt that.

The cheeky incidental music to Hamlet offers some respite, with its swooning “Funeral March,” frolicking ditty for Ophelia, sweet “Cradle Song,” and stern-but-not-too-serious “Requiem” replete with iterations of the “Dies irae” chant. Nelsons and the BSO play it all with verve and spirit, but the overriding expressive affect here is one that involves much pain and suffering.

Then again, that’s life – and it certainly was Shostakovich’s story. That he left such a musical testament is, in its own way, miraculous; that it continues to speak to us with immediacy and power only reflects the enduring tragedy of the human condition. How good to have documents like this, then, to remind us that we’re not the first, or the only, or the worst-off ones to have experienced hardship and loss.

And how welcome to hear it from the BSO, an orchestra that’s been through its own emotional wringer these last several years (though admittedly nothing to compare with Stalinist terror or Hitlerism). If the first volume in this series announced that the orchestra’s back after a hiatus, this latest one declares that it’s here to stay for a while.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette

Tagged: Andris Nelsons, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon, Dmitri Shostakovich