Book Review: Classic Coming-of-Age?—The Chester Chronicles

Kermit Moyer’s exquisitely written book, conceived with the greatest care and written with an art that conveys artlessness (the highest art of all), is a welcome addition to the American canon.

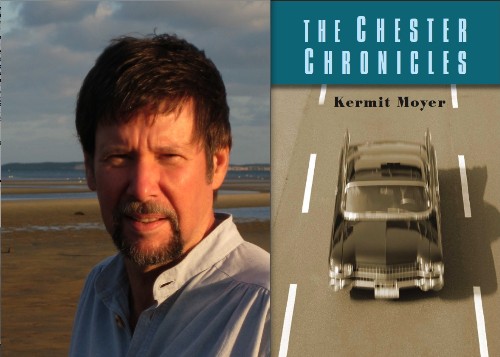

The Chester Chronicles by Kermit Moyer. Permanent Press, 231 pages, $28.

By Roberta Silman.

As the epigraph for his first novel, Kermit Moyer quotes writer Andre Dubus, who said, “Our lives are not novels. They are a series of stories.” And then we begin to read a wonderful book, a true coming-of-age novel in the form of 16 stories that actually comes of age instead of dwindling off into vague promises. Moyer, whose earlier collection of stories is called Tumbling, has a terrific eye for detail and writes with an uncommon precision and grace.

His protagonist is Chester Patterson, an Army brat born in the mid-40s whose family moves every few years and whose name, which sometimes metamorphoses into Chessie or Chet, is the bane of his existence. The stories, several of which were published in The Hudson Review, can stand alone but as a series give us the picture of a boy growing up from about the age of eight until his mid-20s during a turbulent time in America. Blessed, or perhaps cursed, with a gorgeous, sexy Mom, Chester seems to have sexual longings earlier than most kids. Or it may be as he so eloquently explains:

Military kids, who are always in transit, seem even more sex-crazed than our civilian counterparts—maybe because we have no stake in any particular place or community. We’re free agents in one way, but we’re also officially designated as “Dependents,” completely bound to go wherever our fathers’ orders happen to send them.

That combination of dependency and freedom make for some interesting adventures, and for the first third of this book, I was charmed by this bookish child’s struggle to make his way in an ever-changing, sometimes confusing environment. But Moyer has learned from all his reading, and he has bigger things in mind, as we suspect after he tips us off that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is his favorite book, one he has even read aloud to his younger sister, Janet.

At just the point where I was thinking this was a charming little book, it opens up and becomes a much bigger book—plunging us into those turbulent times where the larger themes of race and politics and age-old questions of what is right and true emerge with stunning immediacy and endear us to Chester in completely unexpected ways.

For this is a boy who is quite ordinary looking and not very athletic, not good credentials for someone who is always the “new boy.” So he escapes, as many lonely youngsters do, into a world of books, delighting the reader with his delight in the books that mean so much to us when we are young. As I read, I thought, some smart high school teachers ought to put this book into their curriculum, for here, at last, is a book small enough for kids to put into their backpacks but large enough to wake them up and broaden their view of the world. They, like we, will be riveted by Chester’s adventures in high school and college, his growing concern about his mother’s drinking, his increasing appreciation of his younger sister, Janet, and his discomfiting awareness of all the nuances of his parents’ marriage.

His growing maturity underlines what he knows: “Because reading A Farewell to Arms confirmed something I always seem to have known: nothing is free. You had to pay one way or another for every good thing that came your way.” But, like many heroes in our American literature, Chester is a slow learner, and when he gets to college and thinks he has it all, in “The Calliope Diaries,” he comes to conclusions worthy of Chekhov; indeed, the mood and voice of that story reminded me not only of Chekhov, but also of Turgenev’s great story, “First Love” and Joyce’s “Araby.”

Unlike Holden Caulfield, who has clearly had an influence on Moyer, Chester grows up and stops blaming everyone else for the bad things that happen in life. His view is larger than Salinger’s, perhaps because of his peregrinations as an Army offspring, perhaps because of the times he lives in, and, mostly likely, because Moyer has ambitions more like Fitzgerald than Salinger. What a relief to read, after he learns that an Indian woman he has befriended is bending to what she calls her fate

I had the sensation of discovering, like an article of faith, the very bedrock of my own personal philosophy, which was simply this: everyone was responsible for his own fate. Period. End of story.

And when he comes to grips with the racial problems that have been hovering over many of these stories and the personal tragedy in his own life, you close the book feeling you have entered someone’s else universe with a completeness rarely found in American writing today. For this exquisitely written book, conceived with the greatest care and written with an art that conveys artlessness (the highest art of all), is a welcome addition to the American canon.

Bravo, Kermit Moyer!

=======================================

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She has recently completed a new novel, Secrets and Shadows. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Stopping blaming and taking charge is always the beginning of freedom.