Literary Appreciation: “The Passion for the Thing” — An Argument for Writer Harry Crews

The teeming, Southern-inflected melee of Harry Crews’ universe, like a Hieronymus Bosch canvas dipped in whiskey and flour and deep-fried, will continue to attract readers for generations to come.

by Jay Atkinson

I studied under Harry Crews. I knew Harry Crews. Harry Crews was a friend of mine. And I’ve never met anyone as blunt, compelling, controversial, flawed, or talented as he was — and I’ve been around. At age 71, chain-smoking like an air traffic controller during the Reagan administration, Crews told a New York Times reporter: “I had an ex-wife and I had an ex-kid and I had an ex-dog and I had an ex-house and I’m an ex-drunk.” Now, four years after the volatile writer’s death (June 7, 1935 – March 28, 2012), and upon publication of Ted Geltner’s Blood, Bone and Marrow: a Biography of Harry Crews (University of Georgia Press, 406 pages, $32.95), I’m drawn back to my recollections of Harry as a writer, teacher, and friend.

Crews had a temper as short as his life was long, burning more bridges than General William Tecumseh Sherman as he rampaged across Georgia during the Civil War. Despite his I-don’t-give-a-shit attitude, Crews was the author of 23 books, including his celebrated memoir, A Childhood: the Biography of a Place, and a startling array of gritty southern novels, including The Gypsy’s Curse, A Feast of Snakes, Naked in Garden Hills, and Body. Born in Bacon County, Georgia, at the nadir of the Great Depression, Harry arrived at the University of Florida in the 1960s after a three-year hitch in the Marine Corps. I enrolled in Crews’ fiction writing seminar in the UF graduate school for eight consecutive semesters between 1980 and ‘82. By the time I met Crews, he’d drank himself past the dark good looks and chiseled torso of his early publicity photos. Dressed in Sears Roebuck jeans and ill-fitting polo shirts, he was a large, shaggy, sore-legged wreck in his mid-forties, known for holding forth in his gravelly voice with a mesmerizing admixture of erudition, insight, and profanity.

Walking into Harry’s class was like an aspiring trapeze artist going under the Big Top with P. T. Barnum. Crews didn’t just teach — he evangelized. This was classroom as performance space, teaching as theatre. In light of all the hardships he’d endured in willing himself to become a writer, Harry had little tolerance for those who weren’t dedicated to the craft. I can picture Crews, in all his ragged glory, stabbing his finger at the ceiling: “The thing! The thing! To have the passion for the thing, and to remain true to it — despite everything that’s going to happen to you, the heat, the grief.” It was the sort of charged atmosphere that appears to have vanished forever, and remembering how much I loved it makes it seem even more distant.

Everything Harry said in that stuffy classroom grew out of his long, painful apprenticeship, and the haunting memories of his early life. On their dilapidated tenant farm, the Crews family survived on the paltry crops they scratched out of the loose gray dirt, and whatever they caught or killed. As an infant, Harry suffered the premature death of his father, Ray Crews, inheriting Ray’s mean, hard-drinking brother, Paschal, as his stepfather. When he was five years old, Harry contracted polio, bringing on a temporary bout of paralysis and forcing him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. A few months later, rough housing with other kids, young Harry was knocked into a vat of boiling water meant for skinning hogs, which burned him over two-thirds of his body. That same year, his stepfather, in a drunken rage, fired a shotgun over the head of Harry’s mother, Myrtice Crews, and she decamped for the poor section of Jacksonville, Florida with Harry and his older brother, Hoyett.

Whenever these stories came up, Crews would quote one of his literary heroes, Flannery O’Connor, who wrote, “The fact is that anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days. If you can’t make something out of a little experience, you probably won’t be able to make it out of a lot.”

Of Crews’ legendary and tumultuous youth, I’m reminded of what my father used to say about my great uncle, Jack Maynard, who ran away at 16 to enlist in the British Navy during WWII: “If half of what he says is true, he’s tough as whale shit and twice as stinkin’.” But Crews, in his manner and his work, was not so much concerned with the literal accuracy of his stories as he was their moral truth. Harry had grown up maimed, scalded, and crippled, among hard living, inarticulate folk who had also been mangled and maimed, and the terrible beauty of what he saw there came out in the addled bodybuilders, boxers, and karate masters; the brokenhearted dwarfs, freaks, hucksters, paralytics, and whores that populated his fiction. In this way, the teeming, Southern-inflected melee of Crews’ universe, like a Hieronymus Bosch canvas dipped in whiskey and flour and deep-fried, will continue to attract readers for generations to come. The work of Harry’s semi-contemporaries, including John Updike and his fixation with middle class, middle aged adultery; Norman Mailer’s all-consuming fascination with himself; and Phillip Roth’s slick, masturbatory condescension are already fading from the public conversation, while Crews’ frightening but ultimately cathartic and sympathetic tales of society’s outcasts and misfits are primed to endure. He took the hard-bitten rural characters of William Faulkner and O’Connor and warped them outward, exaggerating them almost beyond recognition, tying them to what Faulkner called “the old fierce pull of blood,” and yoking them to an increasingly shallow, menacing, and doomed modern world. Enter Crews’ depiction of that world, and you’ll never be the same again.

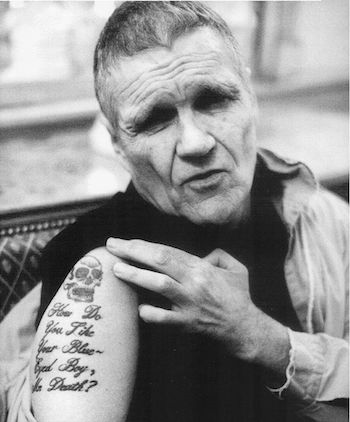

Harry Crews showing off a tattoo. Photo: courtesy of Ted Geltner.

Crews is sometimes dismissed out of hand because Southern Gothic literature, which is one way of describing what he practiced, is limited by its regionalism. But that ignores the central feature of “Grit Lit” — the genre’s first principle — that the land itself is the enduring hallmark of Faulkner, O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty, and the rest. That is, the single most important element in the story is the real estate where it occurs. From Harry I learned that all the best storytelling is rooted in this sense of place; that the characters are integrally connected to their own ground, and that the ground binds those characters to one another. And there’s no ground more saturated with blood, failure, sweat, tears, and pride than the American South. If three generations of Crews’ writing students learned nothing more than that, their tuition money was well spent.

Like the man himself, Harry’s darkly comic vision of American life has staying power. He may have, at times, been overwhelmed by the self-hatred and torment that often possesses artists, but he genuinely loved the characters in his fiction and cheered for their humanity. Aside from the question of whether readers one hundred years from now will consider a novel such as Harry’s Car, about a man who eats an entire Ford Fairlane, bumper to bumper, as representative of the late twentieth century over, say, Updike’s Rabbit, Run or Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, is the fact that not many heavyweight writers of Crews’ era distinguished themselves as teachers. (John Irving, a bit younger than Crews, might be an exception, and perhaps John Gardner, the author of Grendel and several other books). In that respect, Harry has beaten most of his peers by a country mile.

When I attended the University of Florida, Crews was going through a lengthy dry spell after publishing his first nine novels in only ten years. But that didn’t seem to faze him. One night, Harry and I were walking across campus, and he confessed that, after delivering an especially dazzling burst of hortatory exclamations, where a kind of St. Elmo’s fire jumped among his students like blue lightning, he’d saunter down University Avenue, muttering to himself: “Son, you may cain’t write, but you sure can teach.”

Among the revelations in Geltner’s Blood, Bone and Marrow (Note: I was interviewed for the book) is the time that Crews, on a 1958 motorcycle trip across the U. S., met Jack Kerouac in San Francisco. Kerouac had become famous a year earlier, when his second novel, On the Road, was heralded as the most important work of his generation. Apparently, Kerouac’s presence intimidated a lot of people, but Crews, who hadn’t published anything yet, ran into the Lowell, Mass. native in a Haight Asbury bar and tried to engage the shy, Franco-American writer in conversation.

Kerouac was my literary idol when I showed up in Harry’s class, and during that first month I was working on a story called “Gainesville Blues,” which was set in the rundown boarding house where I was living and included passages cribbed from the Kerouac playbook: “Mrs. P. has this slinky-stinky fake satin bathing suit with a watermelon curtain for her stomach and she grabs my ass every time I squeeze by her in the narrow kitchen…”

Harry let me continue in that fashion for a while, holding his tongue. During one of our meetings, Crews said that my stuff would never be anything more than warmed over Kerouac unless I learned to tell stories in my own voice. Then he pushed a small, dun colored book across the desk to me. It was Dispatches, by Michael Herr.

“Take it home and read it,” said Crews. “And when you’re done, read it again.”

I still have that worn hardcover edition of Herr’s harrowing experiences as a young reporter during the Vietnam War. I’ve probably read Dispatches twenty times, given it as a gift, and often recite my favorite passages in bars and at rugby parties. Early on, Herr writes, “Talk about impersonating an identity, about locking into a role, about irony: I went to cover the war and the war covered me; an old story, unless of course you’ve never heard it.” By handing over that book, Crews was not saying “write like me”, or even “write like Herr.” There was no anxiety of influence with Harry. In performing that simple action, he revealed more about his character than he would have in a half hour soliloquy on writing prose fiction. He knew that if I read Herr’s book, I’d figure out that a writer can accomplish more by adopting a plain style over an ornate one; that by keeping his or her cadences brief and bright and sharp, a writer can maintain control of the narrative, stopping at opportune moments to embroider on that style, to provide the right flourishes. It’s also noteworthy that Harry practiced this technique in his own work, demonstrated by the opening of his memoir, A Childhood: “My first memory is of a time ten years before I was born, and the memory takes place where I have never been and involves my daddy whom I never knew.” Here was another Crews lesson salvaged from all those unproductive hours, all those crumpled up pages.

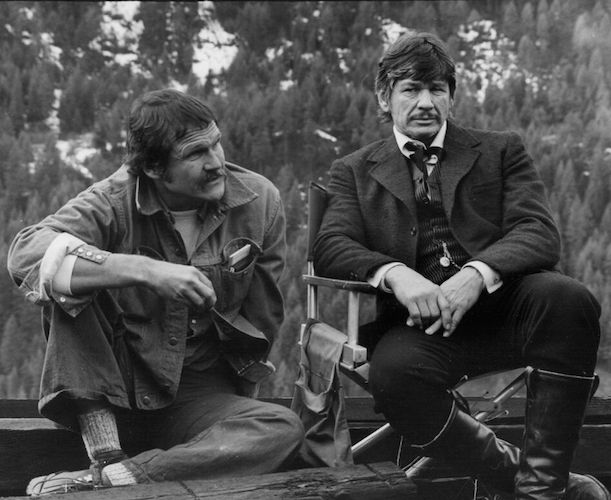

Harry Crews and Charles Bronson on the set of the movie “Breakheart Pass.” Crews was writing a profile of the actor for “Playboy.” Photo: Ted Bell.

Now that I’ve published a few books and made the acquaintance of quite a few writers, I realize how generous Harry was to his peers, as well as his students. Writers can be a selfish, thin-skinned lot, more focused on their own careers than anything else. But Crews would go out of his way to help lesser-known writers, and was inundated with advance reading copies of all sorts of books, sent by publishers eager to land his blessing. (Crews provided a jacket blurb for my first two books, until I dedicated my third, Legends of Winter Hill, to him, and figured it was time to sink or swim on my own.) During another meeting, Crews pulled out a first novel he’d received in the mail. The author’s photo depicted a matronly, middle-aged woman with a bouffant hairstyle and cat-eye glasses.

“She writes just like she looks,” said Harry, gazing at the book. “But I gave her a strong review, because she had to beat long odds to get where she is.”

After a few wild misadventures early in our acquaintance, some of which are described in Geltner’s book, I spent the bulk of my free time with the other guys on the UF rugby team, seeing Harry mostly in class and around campus. Back then, and for twenty years afterward, Crews engaged in an embarrassing skein of loutish drunken behavior, the perennial adolescent, leading a coterie of young male acolytes he called “the boys with the high pectorals.” But emphasizing all that, as many observers have, misses Harry’s essential decency. For in spite of his abrasiveness and bluster, Crews was a sensitive, caring, goodhearted man. Certainly, he made mistakes. Over the course of Harry’s life, he suffered from addictions to amphetamines, booze, cigarettes, cocaine, falconry, fast cars, karate, long distance running, and weightlifting. But his most persistent habit was the compulsion to write — the habit of storytelling. It saw him through an abundance of tragedy, including the accidental drowning of his three-year-old son, Patrick, which would have destroyed a hundred strong men. In a real sense, Harry’s weaknesses were his salvation.

Late afternoons, I often found Harry alone in the creative writing suite, reading or smoking a cigarette. These are among my most cherished memories of him. During those times, Harry was usually in a genial, reflective mood, quick to laugh, and to offer advice. When an attractive young reporter called Harry for an interview, and offered to publish something he’d written, he suggested an up-and-coming young writer instead. That afternoon, the reporter picked me up in her yellow convertible. We dated for several weeks, and the magazine published one of my early stories. In my final semester, Harry chose me and another student to read from our work at a gala literary event honoring the Nobel Prize winning poet, Czesław Miłosz. Milosz was a formidable, serious looking man with bushy eyebrows, and as I stood at the lectern, nervously shuffling the pages of my story, he stared intently at me from his seat in the front row. Leaning against the wall, Crews, looking relaxed and pleased, merely winked.

Harry was not a cruel taskmaster, but he was stingy with praise. Upon curing my Kerouac affliction, he suggested I start writing about episodes from my youth that took place in Lawrence, Mass., a grand old mill city in steep decline. One of those stories dealt with a thirteen-year-old narrator who was playing on a hockey team several levels above his age group. One night, waiting for a ride to his game, the boy was carving out shards of the curbstone with his hockey stick, and “wristing” them down the street, occasionally pinging one off a car fender. For some reason, this image delighted Crews.

“I don’t know the first goddamn thing about that sport,” Harry said. “But I can see that.” He made a motion with his hands, like he was shooting a hockey puck. “You just snap it around.”

Harry Crews and Jay Atkinson in 2010. Photo: Jay Atkinson.

When I was ready to graduate, Harry said I should write a novel. Previously, I‘d turned in a few colorful stories about my undergraduate days in Nova Scotia. “Write about your boys up in Canada,” he said. When we parted that afternoon, Crews added, “See you in ten years.”

He wasn’t kidding. A decade later, my first short story, “Imagine Lawyers Behind Every Chippendale Armchair”, appeared in the Chattahoochee Review. Then, in 1997, my rugby novel, Caveman Politics, was published. But in a dusty manuscript box in my hall closet is a 300-page draft of that first, unpublished novel, Local Talent, painstakingly tapped out on a manual typewriter in several drafts over five years. There’s even a character that resembles Harry Crews. He’s a hard drinking, middle-aged ex-Marine who puts on his mothballed dress blues to confront a group of thugs who have been threatening people in their seaside town. Every once in a while, I take down the box and read a few yellowed pages. That book is Harry’s gift to me, as well as everything that came after it.

I visited Crews in Gainesville, Florida in January 2010, which was our first meeting in twenty-eight years. His face was a magnificent ruin, like an old Viking’s, but his eyes were a bright, clear blue, as always. Wracked by pain from a number of ailments, Harry couldn’t stand up, so I leaned over and said, “Give me some love, big guy,” and he laughed as we embraced. All that morning, my old UF rugby pal, “Surfer” John Hearin and I re-enacted several funny episodes from our shared adventures in Gainesville, while Harry added his profane commentary, downing bottle after bottle of green tea. It was the last time I ever saw him.

Although Harry delivered sermons that rivaled those uttered by the corn crib preachers of his youth, he didn’t attend church and hardly ever talked about religion. Still, Graham Greene and Flannery O’Connor, both Roman Catholics, were two of Crews’ favorite writers. I always believed that Harry envied the Catholics for their embrace of the gloomy rituals and mysteries of the faith. Or maybe it was the doctrine of sinning and being forgiven, of being broken and made whole again, of attaining grace. The fact that I was a blue collar Irish Catholic from Massachusetts seemed to endear me to Harry in some way. So it’s only fitting that every night since he died, I’ve said a Hail Mary for my mentor and friend, an act of devotion previously reserved for a hockey teammate who died young. Then, before drifting off to sleep, I add, “Dear Mary, say a prayer for Harry Crews, and ask your Son to permit Harry into His Kingdom. Harry was a good man, and he tried his best.”

Jay Atkinson is the author of two novels, a collection of short stories, and five narrative nonfiction books, including his latest, Massacre on the Merrimack. He teaches writing at Boston University. Follow him on Twitter@atkinson_jay, or on Facebook

Tagged: Blood Bone and Marrow, Harry Crews, Jay Atkinson, Southern literature, Ted Geltner

Poignant and beautiful. The author’s ability to recognize and appreciate the many layers which made up the man, his mentor – Harry Crews, spotlights the depth of their connection. Very touching.

Perhaps the greatest benefit of being a teacher is the possibility of becoming a transformative force in a young person’s life. The author of this article was “that teacher” for me. I remember his stories about Crews back when I was an undergrad at UMass Lowell. And now, more than two decades later, I tell stories about both Atkinson and Crews to my own students.

Thanks, Jay, a joy to read, first sentence to last, from booze to green tea.

Extremely touching article. Crews is fascinating to read; He must’ve been infinitely more layered and inspiring to know. “To have passion for the thing, and to remain true to it – despite everything” – wise and inspiring words from a passionate writer and man.

Beautifully written piece about an incredible man. Did not know Mr. Crews personally, but from the stories I’ve heard he was an amazing individual with a passion for writing unrivaled by any other. I look forward to reading the book, and of course reading it again as I know that’s what Mr. Crews would expect! Wonderful article!

As a philosophy student who refuses to give up on his love for writing, despite the horrifying prospect of entering the ‘real world’ in one week, this article is an inspiration. This tale of friendship between Crews and Atkinson deeply rooted in a love for writing and the fringes of humanity speaks towards what life could be in its full depth, so to speak. Atkinson is “that teacher” for me as well and I am excited to read about his “that teacher” in Blood, Bone and Marrow!

I never really realized the complexity of storytelling until I had Jay Atkinson as a professor this past semester. Jay has a unique background that has factored into not only his teaching career, but his career as a writer as well. Harry Crews is an integral part of that background for Jay as he referred to Harry Crews a lot in class. It’s clear that the man had a great impact on Jay from his days as a grad student at UF to the present day. What Jay has taken away from Crews and has ultimately instilled in his students is to utilize the power of your own voice and experiences to tell a story. As an aspiring journalist, this is a skill I value immensely and am going to work to perfect throughout my career. No matter if it’s writing a novel, article, or interviewing someone for radio/television, the ability to recognize the relationship between your surroundings and your experiences there and people around you can go along away in telling the stories that haven’t been told yet. A big thanks to Jay for sharing his experiences with a writer of such a revolutionary era.

Amazing piece. After having Jay as a professor, it is incredibly fascinating to see how Crews influenced him and likely many others. We are all products of our mentors, so to learn in great detail about the mentor of someone I consider to be one of my mentors was both touching and poignant. The work of Crews lives on not only through Jay, but also through Jay’s students like me. His legacy will carry on.

Jay,

This was a really good essay. You talked a lot about him in class and from your description I was able to imagine the scenes in your story. He seemed like an interesting person to be around and learn from. I could also see how he has influenced the way that you teach your class. Thanks for sharing!

I had Jay as a professor my freshman year at Boston University, and I distinctly remember the Harry Crews stories that would inevitably come into play at least once a week. Reading this article was a great reminder of just how much someone can influence a person for the better and vise versa. I’m so happy to have had Jay as a teacher and also a friend, and I believe Harry Crews had a big hand in making Jay the awesome storyteller he is today.

Great read from the perspective of a mentee, a lovely look into Crews and his nature

What an amazing piece. I particularly liked the ending. A really great read. Like many of the comments above, I was a student of Jay’s at Boston University as well and often heard about Harry Crews in class. Now I understand why, and it couldn’t have been a better story. Well done!

It was a decade ago when the author of this piece inspired me to pick up a copy of CLASSIC CREWS. Much like how Harry changed Jay’s life with DISPATCHES, Crews’ masterpieces introduced me to an important voice in American writing that continues to influence my own work. His writing transports you into the story, letting you walk alongside his crippled, life-worn heroes. Jay’s essay does the same, bringing us into Harry’s life. The article definitely makes me want to pick up Geltner’s book to learn more about the towering figure that is Harry Crews.

Well done, Jay! Crews is missed, and your remembrance is appreciated.

What a great testimony! I really get it when you say that he cured you from Kerouac… I have the same problem with Bukowski/Fante… and now that I’ve read A Childhood, it seems that I’m hooked… I wish that it will help me define my style…

This is really beautifully written, thanks for giving us a sense of the man from someone who really knew him.