Film Interview: Saving Serious Cinema Conversation, One Salon at a Time

The process is simple: watch a film at the salon that’s been picked because it is “likely to inspire discussion,” says David Kleiler, “or is in need of reappraisal” and talk about it afterward.

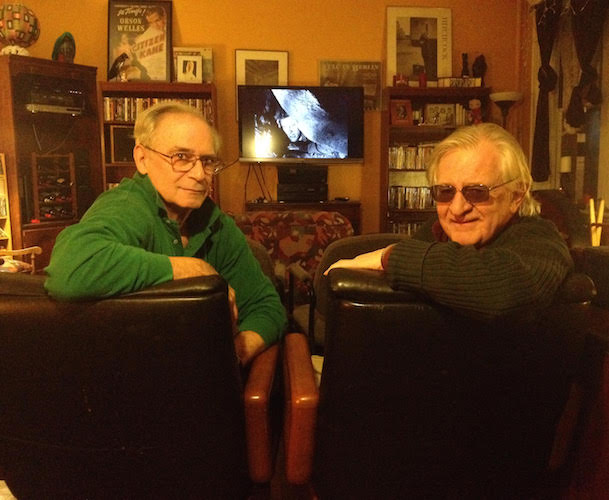

Cinephiles Jean-Paul Ouellette (l) and David Kleiler (r) — keeping off-Internet and in-person discussion of movies alive and well. Photo: Steve Head.

By Steve Head

In his September 2012 article entitled Is Movie Culture Dead? (which was published in the wake of the New York Film Festival), Salon.com’s Andrew O’Hehir argues that:

Film culture, at least in the sense people once used that phrase, is dead or dying. Back in what we might call the Susan Sontag era, discussion and debate about movies was often perceived as the icy-cool cutting edge of American intellectual life. Today it’s a moribund and desiccated leftover that’s been cut off from ordinary life, from the mainstream of pop culture and even from what remains of highbrow or intellectual culture.”

To that, The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody responded, “O’Hehir’s comment about cocktail-party chatter” signifies “not getting out enough” and “not knowing people who can tell him otherwise.”

I’d like to introduce Mr. O’Hehir to my Diabolique Webcast co-host David Kleiler and fellow cinephile Jean-Paul Ouellette – both of whom are actively committed to keeping thoughtful off-Internet and in-person discussion of movies alive and well. In August of 2015, they began regularly hosting “screening salo(o)ns” or “salons” in the living room of Kleiler’s Brookline, MA condo. These informal and informed gatherings of friends, colleagues, and ardent cinephiles usually take place five or six times a month.

“We’ll start at 7 p.m., but we usually don’t start the film until 7:45 because there’s food and drinks beforehand,” says Kleiler. “People will bring things. There’s a time to schmooze and relax. We’re not in a hurry. Because of that, there’s already a comfort level. People know each other already, but some people may be attending for the first time.”

These days, it’s not that people are any less enthusiastic about films, it’s more that the viewing options have expanded and the places where people can discuss films have changed. That being the case, Kleiler and Ouelette have instituted an informal gathering for watching movies seriously, in ways that Kleiler has been doing for years. The process is simple: View a film that’s “likely to inspire discussion,” suggests Kleiler, “or is in need of reappraisal” and talk about it afterward.

Hosting screening salons is nothing new to Kleiler. He began doing so more than forty years ago when he was teaching film at Babson College and Adult Education classes at Brookline High School. Back then, only 16-millimeter films could be shown in class. Kleiler decided not to waste the students’ time by showing movies in class; he screened them outside of class, and at home. Family, students, colleagues, and neighbors soon joined him in watching the films and some became caught up in the infectious pleasure of gabbing about them.

“The 16mm reels were about forty minutes long,” recalls Kleiler, “so we’d have wine and cheese between the reel breaks. And so this is always been part of what I’ve liked. But now, we’ve sort of upgraded the experience.”

In the eighties, Kleiler made his love of film mobile and founded the Rear Window screening series, which showed 16mm films in various locations around Boston. Rear Window’s motto was “Obscure films in obscure locations.” Along with his projectionist, Dima Balin, Kleiler screened movies in arts centers, restaurants, and bars. “The idea of seeing the film and having a conversation over a few drinks has always been a concept I liked,” says Kleiler. “I like watching movies with people. I like being able to share insights and enthusiasm with people, and that’s really it.”

From the late eighties through the nineties Kleiler led the effort to save Brookline’s Coolidge Corner Theatre (afterward becoming its program director). When he formed the company Local Sightings, which “is committed to supporting independent filmmakers and the independent film community at large by offering a wide variety of services that help projects get made, sold, and seen,” the salon became an off-and-on event. Jean-Paul Ouellette – an accomplished writer and director whose films include The Unnameable (1988) and Chinatown Connection (1990) – helped make the screening series a more consistent happening.

“At that time David was intermittently hosting the screening salon,” says Ouellette. “He wasn’t feeling as though he could be more consistent hosting them. But I said, ‘We can do this. Let’s take it another step forward and formalize it.'”

Ouellette, having worked in the film business in Los Angeles, was well accustomed to film gatherings. “With friends we’d get together and go see a film and go some place afterward and talk about it,” he remembers. “We would go out for dinner or something. Now I see less and less of that. It’s part of the reason why, in a way, that film’s value has dropped a little over the years. Films aren’t as important as they used to be. They’re essentially becoming television, not the communal conversation pieces they used to be. This salon is an answer to that.”

Another element that’s central to the salon, apart from its mission to revive in-person conversations about cinema in the Internet age, is that everyone who attends is encouraged to participate in the post-screening conversation. Kleiler and Ouellette make it clear that it’s not about them holding court to inform others. It’s about sharing responses and everyone learning from the process. “It’s a give-and-take,” insists Ouellette. “And I believe this immediate interaction inspires deeper views on cinema.”

“We can accommodate as many as twenty-two people, and we have,” says Klieler. “But when it’s over sixteen it can kind of affect the quality of the discussion. Our ideal attendance is around eight to twelve. We want to make sure everybody gets a chance to talk. And since we’re not doing social media type of film discussion, the key thing is live interactivity. There’s a whole human and social dimension to this experience. Everyone goes through their own analysis of things.”

Although Kleiler describes himself as “a technophobe” who doesn’t feel guilty about missing online conversations, this doesn’t mean he completely dismisses the Internet; if nothing else it is vital to keeping salon attendees informed about past and future screenings. An email list is maintained to inform and update members about future screenings. And their website was also created to spread the word and inspire acolytes.

A scene from Akira Kurosawa’s “Hamlet”-inspired noir “The Bad Sleep Well” — one of the films that made for a lively session of the salon.

One of the key aspects of hosting a successful screening salon is curating films. In the early years, the choice of films was determined by which available 16mm prints Kleiler had for his classes. Over the years, the process has evolved considerably. The titles chosen to be screened are suggested by salon members, partly because Kleiler is keen to find out which films others believe need to be seen again and are worthy of reconsideration. What it comes down to is: Is the film worth discussing? As a result, Kleiler has been invited to rethink earlier evaluations; he now has greater appreciation for Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels, Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie, and Akira Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well. Kleiler and Ouellette also want a challenging variety of films, not just classics. “After a number of films of a certain type, we’ll go back to something more obscure,” states Kleiler, “like Upstream Color and Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy, both of which I’d never seen. I don’t want the salon to run just one kind of film.”

As a testament to their open-mindedness, Kleiler and Ouellette will even screen movies they don’t particularly like, as long as they have some edifying significance. “I’ll show them,” says Kleiler, “I’m fascinated by the idea of someone liking a film I don’t like and offering a completely different perspective on it. People who dislike a film can have as much to say that’s interesting as the people who like it. People can put a movie they don’t like behind them really quickly. But here you’re encouraged to discuss your reasons.” The bottom-line imperative is for salon members to articulate why they think a particular film is good or bad — the very kind of ‘intellectual’ discussion and debate that O’Hehir posits, from his condescending perch in his hermetically-sealed Salon, is as dead as a dodo in today’s thumbs-up, thumbs-down culture.

On the other hand, there are some films Kleiler will never screen: “If someone asked me to show an Adam Sandler film or The Human Centipede I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t. It’s not a democracy.” But there is an equalitarian spirit to the salon: it is about sharing cinematic pleasures and perspectives in a convivial communal setting. “I’m just doing what I’ve always wanted to do,” concludes Kleiler. “It’s my whole life’s ambition really. I didn’t want to do anything more then hang out, watch films, have a few drinks, and talk about movies.”

Steve Head is the host of the Diabolique Webcast at DiaboliqueMagazine.com and The Post-Movie Podcast at Post-Movie.net. He co-created the much loved movie news website IGN FilmForce (now IGN Movies), was a staff writer and content producer for IGN Entertainment (2000-08), and a writer for America Online, Netscape, and Propeller.com. He earned a B.A. in History from Providence College. And he helped make some movies, some of which are listed here. You can follow Steve on Twitter.

Tagged: Cinema Salon, David Kleiler, Diabolique Webcast, Jean-Paul Ouellette, Salon