Book Review: “Cooking With the Muse” — Poetry and Food, Transformed

Though the culinary tastes in this book are original and often complex, the recipes themselves are breathtakingly clear and often very simple.

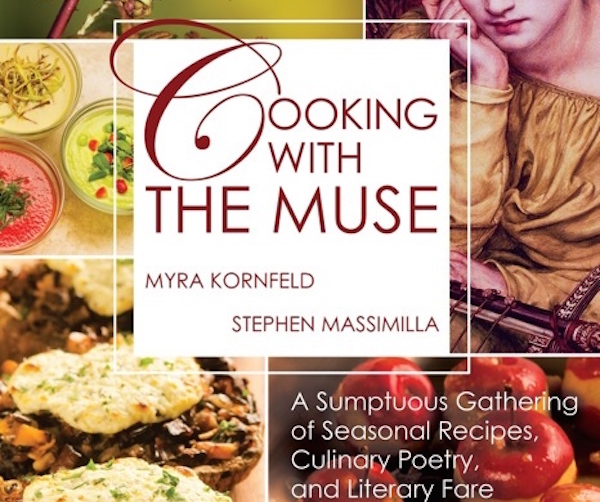

Cooking with the Muse: A Sumptuous Gathering of Seasonal Recipes, Culinary Poetry, and Literary Fare by Myra Kornfeld and Stephen Massimilla. Tupelo Press, 500 pages, $34.95.

by Grace Dane Mazur

A great cookbook is meant to be devoured as much while reading on the couch as while pacing in the kitchen; a great poetry anthology is as inspiring by the stove as in the living room. Cooking with the Muse: A Sumptuous Gathering of Seasonal Recipes, Culinary Poetry, and Literary Fare , a compendium of 150 recipes, 200 full-color photographs, poetry about food and cooking, culinary and historical notes, and literary essays, is at home in every room of the house, the stuff of dreams and of action, thinking and making. Take it with you if you go away for the summer, or even to a friend’s house for the weekend. You will end up giving it to your friend, but that is no matter, for this book deserves to be widely disseminated. The recipes are adaptable to any sort of food preferences, no matter how restrictive or bizarre.

This book should be equally valuable to the novice and the expert, whether chef or poet. One of the authors, Myra Kornfeld, is a professional chef, teacher, and nutrition expert; the other, Stephen Massimilla, is a poet, critic, professor, and painter.

A generous introduction treats the history of poetry about food and then discusses ingredients — meats, eggs, dairy, fats, grains, natural sweeteners and exotic spices, and finally gives the “foundation recipes” for different stocks based on Chicken, Fish, Meat, or Vegetables. There are even instructions for chopping onions. (After more than a half century of cooking, I have finally learned that for salads one cuts an onion across the grain into half moons, while for sautéing it’s best to slice parallel to the growth lines.) Intellectual generosity runs through the whole volume, from the clarity of the instructions to the “Cook’s Notes” and the “Poet’s Notes” following the recipes, from the depth of Massimilla’s essays to the richness of his own poems. These are sometimes riffs on the exact recipe, as in his “Seared Tuna with Purple Potatoes and Cherry Tomato Sauce” (inspired by Neruda), and always ecstatically sensuous.

The book opens with Autumn and the “the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries” of Galway Kinnell’s “Blackberry Eating.” Massimilla’s accompanying essay notes that “even the word ‘black’ itself, with its four consonants clumped on a single syllable, is like a blackberry,” and he notes how the speaker first tells of his literal love of blackberry picking, and then his love of language as a metaphor for blackberry eating (and vice versa).

The recipe for a parfait of macerated blackberries layered with cream is followed by more blackberries in Mary Oliver’s “August,” which starts: “When the blackberries hang/swollen in the woods, in the brambles/nobody owns,…/

Of course for Autumn there are also many offerings of corn and squashes, such as Hominy, Tomatillo, and Pepper Stew which Kornfeld often bakes inside small pumpkins the size of a softball. But my favorite here is “Spiced Espresso Chocolate Pudding with Whipped Pumpkin Cream,” an ambrosial delight. This is best served in a tall glass, so you can see the cinnamon and chile-spiced chocolate at the bottom, the amber-colored layer of pumpkin cream, and the white layer of plain whipped cream on top.

Though the culinary tastes in this book are original and often complex, the recipes themselves are breathtakingly clear and often very simple. The autumnal “Duck Confit Spiced with Coriander and Star Anise” calls for just duck, salt, two spices and five minutes of your time. Then the oven takes over and works its very long slow beautiful metamorphosis until all the fat has left the meat and the result is crispy, fragrant, infinitely mysterious.

Pomegranates, too, are part of Autumn. Between “Greens with Pomegranates Seeds,” made with bitter escarole, and “Pear-Pomegranate Cornbread Pudding” you’ll find Jane Hirshfield’s “Pomegranates” which ends with not only Persephone but also the rest of Nature and Language acknowledging rhythmic and mortal return to the Underworld:

(…) Yes, they say (that sweetness/

In the mouth mixing with pith,

A difficult promise

Made once to a dark King),

Yes, I will return everything.

Two recipes for Vanilla Ice Cream in the desserts of Autumn — one with traditional cream and eggs, the other with cashews, coconut milk, and coconut oil — are paired with Ogden Nash’s delicious and devastating “Tableau at Twilight”:

I sit in the dusk. I am all alone.

Enter a child and an ice-cream cone.

A parent is easily beguiled

By sight of this coniferous child.

The friendly embers warmer gleam,

The cone begins to drip ice cream.

Cones are composed of many a vitamin.

My lap is not the place to bitamin.

Although my raiment is not chinchilla,

I flinch to see it become vanilla.

Coniferous child, when vanilla melts

I’d rather it melted somewhere else.

Exit child with remains of cone.

I sit in the dusk. I am all alone.

Muttering spells like an angry Druid,

Alone, in the dusk, with the cleaning fluid.

Autumn ends with a recipe for Apple-Pear-Cranberry Crumble followed by Hopkins’s “Pied Beauty” and Massimilla’s accompanying essay.

Winter opens with surprising new ways of making oatmeal and two poems about its dangers and delights: Galway Kinnell’s “Oatmeal,” and the startling “Oatmeal Deluxe,” by Stephen Dobyns, in which the speaker constructs a life-size woman made of oatmeal, “…with freckles/ and a cute nose and hair made from brown sugar/ and naked except for a necklace of raisins./” He then admits “…sometimes I’d lick her in places /that wouldn’t show….”

Winter breakfasts continue with Yam Waffles and the astonishing protein-rich gluten-free “Coconut Breakfast Muffins” which I like to make with finely chopped candied ginger and walnuts instead of berries; perfect for breakfast on long plane trips that begin at dawn. Also in Winter: the world’s best and easiest recipe for sauerkraut, “Ruby-Red Cabbage Kraut,” along with Moroccan, Vietnamese, Turkish, and Indian ways to heat up the palate. I’m still looking forward to all of Winter’s chocolate desserts, starting with the coconut-crusted “Chocolate Tart with Salt and Caramelized Pecans.”

A look at one of the dishes in “Cooking with the Muses” — Tuscan Roasted Tomato Soup with Parmesan-Gruyère Frico. Photo: Tupelo Press.

Spring brings Robert Frost’s “Putting in the Seed,” and Massimilla’s essay on it, and later the surprising “Multi-Mustardy Mustard Greens” with three other forms of mustard – as seeds, as powder, and as Dijon – to complement the wilted greens along with a drizzle of honey and an unexpected dash of Brandy.

I haven’t really cooked into Summer yet – we’ve only just had our first winter blizzard here — but I couldn’t resist sneaking a try of the Turkish “Kofte Kebabs with Parsley and Sumac Onions” in which ground lamb or beef is mixed with a radiance of spices: black pepper, Marash pepper, Urfa pepper, cumin, mint, allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, and salt. The grilled meat patties are served on a bed of sliced onions which have been transformed by salt into a juicy sweetness and dressed with tart sumac and parsley. The whole dish is breathtaking. It is paired with “The Banquet” by Hafiz, which ends:

If someone doesn’t want the pleasure

of such an openhearted garden

companionship, no, life itself,

must be against his rules!

Do Blackberries need Cream? Does a Cookbook need Culinary Poetry and Literary Fare as well as Recipes? Consider the blackberry and the resistance of its tiny segments (the drupelets) before they burst their sweet tart darkness on the tongue. Isn’t that enough? What more is needed? Nothing, says the purist. Nothing, says the poet, just more: blackberries, blackberries, blackberries. But perhaps the chef knows better: Macerate those blackberries with the smallest amount of sugar, she says, and layer them with whipped cream in a tall glass, contrasting white and purple, flowing and contained, smooth and bursting, unctuous and tart… And if the cream itself is a mix of sweet cream and crème fraîche, the simple round fattiness of the one will be tempered by the cultured ferment of the other. Such simple operations: macerating, whipping, mixing, layering — the result leaps out of the plane.

So, too, with Cooking with the Muse. The mixture Kornfeld’s kitchen wisdom with Massimilla’s grasp of the world of poetry is a transformative combination. Remembering how the pith among the seeds echoes the dark tremendous promise to Hades at the end of Hirshfield’s “Pomegranates” changes how I taste that fruit. And after picturing the speaker and his woman formed of oatmeal in Stephen Dobyns’s “Oatmeal Deluxe” I think your morning porridge will never be the same.

Grace Dane Mazur is the author of HINGES: Meditations on the Portals of the Imagination; Trespass: A Novel; and Silk: Stories. She has served as fiction editor at Tupelo Press and at Harvard Review. Most recently she has been on the fiction faculty of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College; she has also taught at Harvard Extension School and Emerson College.

Tagged: Cooking, Cooking with the Muse: A Sumptuous Gathering of Seasonal Recipes, Culinary Poetry, Food, Literary Fare, Myra Kornfeld, Stephen Massimill

A delicious and exquisite review!

Oh god. Try the Duck!