Book Review: “The Last Weynfeldt” — The Virtues of a Wry, Cosmopolitan Vibe

In this enjoyable novel, Martin Suter has chosen to sidestep depth in favor of colorful characters fine-honing their hopes and dreams as ploys and counter-ploys.

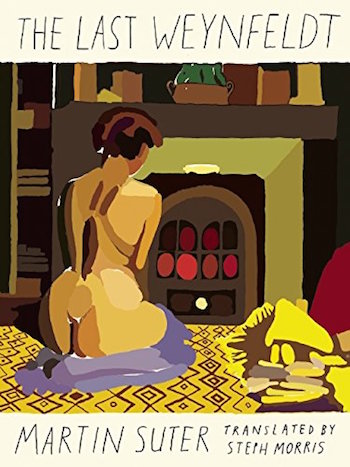

The Last Weynfeldt, by Martin Suter, translated by Steph Morris. New Vessel Press, 302 pp, $14.95.

By Kai Maristed

Oscar Wilde is credited with having squelched a nosy question about his spending a long morning doing some writing by saying, “I took out a comma. On mature reflection I put back the comma.” In other words, punctuation is crucial. We don’t know how long it took Swiss writer Martin Suter to complete The Last Weynfeldt. But we do know that the plot of this engaging novel hinges on the presence — or absence — of a single period.

Suter, a former advertising executive who discovered his knack for storytelling of a different sort back in the ’90s, has been churning out a stream of suavely readable novels ever since. A few became quite successful movies. Strangely, his translated works have yet to catch much fire in the US. Is this because the titles that were hits in Europe, including Small World and The Cook, not to mention the ‘Allmen’ gentleman detective series, were lost in the jungle of US book marketing? Or is it because most American readers simply don’t resonate to Suter’s wry, cosmopolitan vibe? In any case, The Last Weynfeldt — considered by my favorite Munich bookshop to be one of his best — stands a good chance of finding and delighting a wider overseas readership. Many thanks to New Vessel Press for making it available.

Adrian Weynfeldt, the novel’s eponymous protagonist, is a preposterously wealthy bachelor of settled habits. He’s a Feinschmecker, whose tastes run to expensive champagne (in moderation), beautiful paintings of the late 19th and early 20th century, and J.J. Cale’s music. Like his deceased parents, he is a collector of fine art and exquisite crafts, specimens of which fill his spacious Zurich apartment. A secretly shy, middle-aged only child — the eyes of his mother in her portrait follow him around her unaltered room — he is a loner by choice and inclination, although not consciously lonely. In order to maintain social connections, Adrian hosts recurrent luncheons with two sets of acquaintances who couldn’t be more different — on the one hand, the geriatric old pals of his parents, and on the other a checkered group of younger, bohemian, egomaniacal ‘creatives’ — most of whom are chronically in need of the generous financial shots in the arm Adrian is pleased to be able to provide. Is he gay? the old people wonder. Is he guilty about his undeserved wealth? the mooching artists ask themselves. Well, in that case they are really doing him a favor…

To avoid slipping into the slough of idleness — he is Swiss, after all — Adrian works regular hours as an appraiser for auction houses, in particular Murphy’s, a specialist in Swiss art. (Think a boutique, classier Sotheby’s). Regularity in general is a quality Adrian values enormously:

“He owned fourteen pairs of pyjamas, all tailored by his shirtmaker, all with monograms: six light-blue ones for the even days, sic blue-and-white striped for the odd days and two for Sundays — (…) He believed that regularity prolonged life.”

“…Someone you see every month instead of every year never appears to age. And you never appear to age to them.”

“Repetition slows down the passage of time. Weynfeldt was absolutely convinced of this. Change might make life more eventful, but it undoubtedly made it shorter too.”

Why would someone in Adrian’s position, with all his inner and outer resources, allow the days of his life to tick away in such lulling sameness? Of course, there is a woman involved. And, ever since her death, enduring remorse and regret. The one and only love of his youth, lost to a car accident just as he hesitated over whether or not to propose. If he had only insisted that they stay together, that she not leave that night… It’s a touch melodramatic, this back-story, and not particularly moving or convincing. But all that was long ago, mostly washed pale by time. What matters to Suter and to us, the readers, is the novel’s opening moments, on the morning Adrian wakes with a strange woman in his bed, one who looks eerily like his dead love’s twin and yet couldn’t be more her opposite. This mysterious, impulsive, occasionally suicidal Lorena is, as Adrian will learn, a small-time grifter with a chip on each shoulder and no compunctions whatsoever about taking the boring, rich ‘signet-ring guy’ for every Swiss franc she can. But to start with, he has to talk her down from jumping off his balcony.

All of which is entertaining and suspenseful enough. But beneath the glossy surface there is more at stake. Needless to say, the arrival of Lorena puts a swift end to Adrian’s treasured routine. The last Weynfeldt is about to journey through some fundamental transformations. Once the uncanny resemblance has weakened his defenses, it’s the riddle of Lorena herself with whom he falls giddily in love. She is by turns astonishingly frank, a cold-blooded liar, brave and vulnerable, savagely self-protective, and sexy as all get out. Adrian goes from being a pillar of rectitude to an amorous sugar-daddy who knows better but for once doesn’t give a hoot, who will pardon just about any exploitative scheme for an hour with his girl and a champagne-wet kiss. And then… Lorena takes her games of exploitation one step too far. Adrian is blackmailed for a small fortune, the ‘or else’ being not only prosecution for auctioning a forgery of a famous painting by Felix Vallotton, but above all loss of his honor and reputation in the art world. The blackmailer turns out to be a small-time crook and occasional bedfellow of Lorena.

Adrian, coldly enraged, turns wily avenger. Will he survive the threat of scandal, and outwit the bully? Does Lorena have a core of honesty under all her layers of deception? Can this wildly-mismatched couple find the way to each other despite all their self-made obstacles? Just possibly. Remember that period? It’s the one which is, or isn’t, part of the signature of Felix Vallotton on his famous painting, Nude Facing a Stove. What if all could be saved by the addition and removal — or is it removal and addition? — of a period?

The painting exists. (I had the pleasure of viewing it in the rare Vallotton exhibition of 2014 at the Grand Palais, in Paris.) In Suter’s novel, Klaus Beyer, the aging private owner forced by bad investments to part with the masterpiece that’s been his sexual fetish since childhood, describes it thus: “The picture showed a naked woman, sitting on a yellow kilim rug in front of a fireplace filled by a salamandre, a cast-iron stove with a glass door, through which a glowing fire could be seen. (…) Her head was slightly tilted, perhaps contemplative, perhaps submissive; her reddish-brown hair pinned up, her waist narrow, hips broad, buttocks and thighs ample.” Suter himself is clearly not only a lover of fine art, he’s also a portraitist with words, who enjoys taking ample time to sketch a lively cast of secondary characters with a mix of affection and Daumier-like satire that leaves the reader smiling in recognition, sure that he’s met these people in real life somewhere.

Martin Suter, an author of considerable intelligence and sophistication. Photo: courtesy of New Vessel Press.

The theme of art forgery is in vogue these days — there’s been Daniel Kehlmann’s recent brilliant novel F, and the saga of the incredible John Wyatt who, out of prison, now has his own TV show, and a new French film about yet another genius called The Real Forger (my translation), and more. Or perhaps the fascination with forgeries has always been with us, at least from the Shroud of Turin onward. Certainly there’s something strange and poignant about the figure of the ueber-gifted art forger, able to match and in some cases even improve upon the technique of the master — but who lacks an artistic soul of his own. In Suter’s novel, the unsuccessful Rolf Strasser “was a virtuoso painter of every possible technique and style. (…) For a painfully long period he had put his entire energy into losing these skills (…) he went conceptual, left puddles of paint on quiet streets and stretched canvasses over the asphalt so that the cars would leave their marks on them.” Ouch! Poor, villainous Strasser.

Suter handles the gamut of techniques of the writing trade with ease and assurance. In this scintillating send-up of the international art market, crisp dialogue propels the action while spotlighting quirks of character. The settings have the allure of top-notch commercial photography: the food! the paintings and art deco furniture! the handmade shoes and luxury cars, bespoke suits and designer dresses! The radical mood-swings of Alpine weather! and ach du Lieber, the food!

Some readers might regret that, given the author’s intelligence and sophistication, The Last Weynfeldt doesn’t take subjects it touches on — artistic ambition and failure, avarice and fear of aging, the ways in which inherited wealth can be psychologically crippling — to the next level of inquiry. Suter has chosen to sidestep depth in favor of colorful characters fine-honing their hopes and dreams as ploys and counter-ploys. That being said, the plot purrs along like the wheels of a Patek Phillippe watch, leading a frozen, admirably organized man through folly, heartbreak, fury, and despair to his entirely unlooked-for, and delightful, salvation.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other publications. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, a novel set in Berlin. Read her Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

Tagged: German fiction, Kai Maristed, Martin Suter, New Vessel Press, fiction-in-translation