Fuse Interview: Linda Hirshman on How Female Supremes Changed the World

“The question is what piece of the American experience is next going to add the richness of its voice to the Supreme Court.”

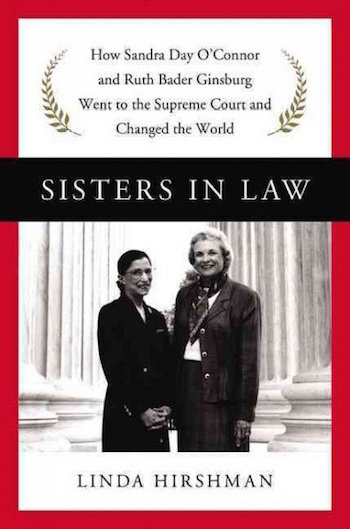

Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World by Linda Hirshman. HarperCollins, 390 pages, $28.99.

By Blake Maddux

After graduating from Stanford Law School in 1952, Sandra Day O’Connor (who was near the top of the class) and William Rehnquist (who was at it) were both offered clerical work: the former as a legal secretary, the latter as a clerk to Justice Robert Jackson of the U.S. Supreme Court. (O’Connor later got her first job working without pay or her own office as a deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California.)

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her legal studies at Harvard, the dean asked her and her eight fellow women enrollees to justify taking up a spot that a man could have had.

In 1981, O’Connor would join Rehnquist on the Supreme Court as an Associate Justice. A dozen years later, with Rehnquist having become Chief Justice, Ginsburg took a seat on the Court herself.

Between graduating from law school and ascending to the pinnacle of the American legal system, O’Connor and Ginsburg became, as author Linda Hirshman writes, “the most famous symbol of a lived feminist existence on the planet” and “the Thurgood Marshall of the women’s movement” (respectively).

Hirshman’s new book Sisters in Law is a dual biography that focuses on the professional and personal adult lives of the first two female justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. Although they approached women’s issues from opposite sides of the political spectrum (while working on opposite sides of the country), Hirshman—who argued three cases before the high court as a lawyer and later taught philosophy and women’s studies at Brandeis University—opines that, “in their strengths they were actually a lot alike.”

There are a few minor quibbles to be had with Sisters In Law: the Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, as noted on page 144, not 1877 (on page 118), and the memo that described one of President Clinton’s nominees as a “cold fish” was about Stephen Breyer, not Ginsburg. These notwithstanding, Sisters in Law is an engaging, informative, and highly readable book that deals thoroughly with legal issues, the fight for female equality, and recent American history in general.

Hirshman spoke to The Arts Fuse by phone ahead of her discussions of the book at the Worcester JCC (November 10) and Harvard Law School (November 11).

The Arts Fuse: What was it like for you to be a student at the University of Chicago Law School in the late 1960s?

Linda Hirshman: The University of Chicago Law School was legendary among its woman students for being a difficult place in the 1960s. There were only seven of us in a class of 150, and the law school has always had a somewhat conservative reputation, as you may know. I talked at an event in New York with a woman who had graduated in the class of ’76, and she asked me who at the law school had inspired me, and I said that [professor] Philip Kurland negatively inspired me. He was one of the great opponents of the Equal Rights Amendment and one of the early representatives of a kind of white male legal intellectual who could tolerate the racial civil rights movement, but could not believe it would actually apply to their wives.

AF: Did you ever argue at the Supreme Court before both O’Connor and Ginsburg?

Hirshman: No. By 1992 I was safely ensconced in the academy. So by ’93, when Ginsburg was appointed, I had stopped practicing law.

AF: What kind of law did you practice?

Hirshman: I was a union-side labor lawyer. My cases dealt with statutory matters having to do with the right to labor unions. Trying to keep my unions alive in a very dark time.

AF: What took you from doing labor law and into academia?

Hirshman: Ronald Reagan took me out of the practice of law. When Reagan was elected in 1980, I realized that the battle to keep the unions alive was going to be a complete rout. I had done the best that I could to keep the retreat from turning into a rout. So I thought that I would go into the academy and wait for a few years for things to get better and things never got better.

AF: What was in the overlapping space of the O’Connor-Ginsburg Venn diagram that made them stronger together and each better off for having the other on the Court?

Hirshman: They were a lot alike in their characters. So the Venn diagram includes their similar behaviors. They were clear about their own values, they took offense when they were pressed to admit that they were not of value, they did not take revenge until it was a productive time to do so, and if they could not get things changed they made themselves deaf. They both manipulated their way through the all otherwise male Supreme Court without one ever making it harder for the other. They were stronger together because they each knew how to manage the men that they were dealing with.

And the fact that Ginsburg was so brilliant and so competent at her job validated O’Connnor’s position that she was not a one-off. She didn’t want to be a one-off, and when Ginsburg came, she really helped O’Connor to not be a one-off.

Author Linda Hirshman. Photo: Nina Subin.

AF: Before Louis Brandeis, people probably did not expect there to be a Jewish Supreme Court justice. Before O’Connor, people were at least—if not more—skeptical of a female justice. Now there are three women, three Jews, and zero Protestants on the Court. What is the chance that one day it will be composed of a majority of women?

Hirshman: Well, the Canadian court has been, and various state supreme courts have been, so it’s not unthinkable by any means. Different things are emerging as salient now. My favorite story in the book in some ways is the last one, which is about Sonia Sotomayor bringing the voice of a “wise Latina woman” and the “richness of her experience.” Sotomayor shows, brilliantly, that there are more experiences—surprise!—even than Anglo people have.

So I think the real question is not how many more women are there going to be, or how many more Jews are there going to be. I think the question is what piece of the American experience is next going to add the richness of its voice to the Supreme Court.

AF: Ginsburg has famously—among Court watchers, at least—questioned the wisdom of Roe v. Wade and O’Connor’s “undue burden” for restricting access to abortion is a pretty high bar. Can you imagine how either or both of them would have voted had they been on the Court in 1973?

Hirshman: I think that they would have voted to strike down the criminal abortion law from Texas. … I think that where they would have broken ranks is that Ginsburg would have voted to strike down as unconstitutional the very much less onerous Georgia law in Doe v. Bolton, which was the case that went up with Roe. I think that Sandra Day O’Connor would have found the restrictions in the Georgia law to be acceptable at that time. States could do almost anything under O’Connor’s test of the “undue burden.”

AF: What would you say to reassure people that Ginsburg is right to not resign simply so that President Obama can select her replacement and thereby eliminate the risk of Republican president doing so?

Hirshman: It’s too late. [The Republican Senate] would never confirm a replacement for her within 11 months of the next election.

AF: Do you have any opinion on whether she should have resigned at a point at which Obama’s selection could have been confirmed?

Hirshman: Both of Obama’s appointments were confirmed by overwhelmingly Democratic Senates. Both Sotomayor and Kagan were appointed before the election of 2010. So what you’re really saying is, should Ruth Bader Ginsburg have retired in June of 2010. That was the month that Martin Ginsburg [her husband of 56 years] died. There was no way that she was going to do that to herself.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received a Master of Liberal Arts from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

Tagged: Blake Maddux, Linda Hirshman, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Connor, Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World