Fuse Theater Review: “Everything Between Us” — A Protestant Perspective On The Troubles

David Ireland’s use of coded sectarian language helps him paint a vivid picture of the Belfast his characters call home.

Everything Between Us by David Ireland. Staged reading directed by Olivia D’Ambrosio. Presented by Solas Nua in Boston at The Burren, Somerville, MA, on October 26.

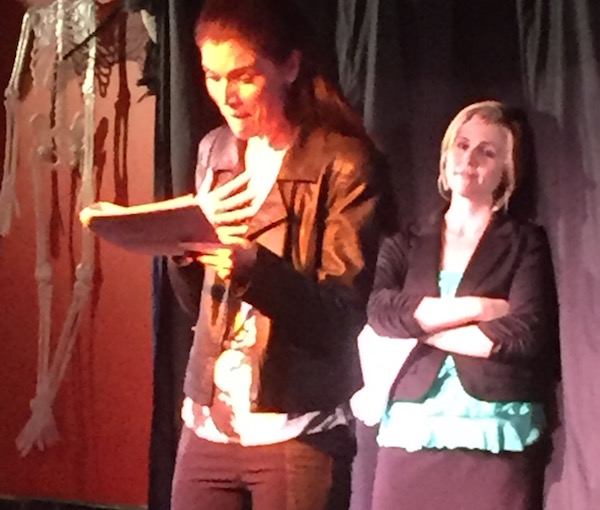

Emma Jayne Gruttadauria and Brashani Reece in a scene from Solas Nua’s reading of “Everything Between Us.” Photo: Courtesy of Solas Nua.

By Ian Thal

Sandra (Brashani Reece) forcefully escorts Teeni (Emma Jayne Gruttadauria) into the backroom of The Burren; Teeni is shrieking an angry barrage of profanity and racial epithets. After they reach the stage there’s some grappling, but that calms down to a shouting match, at which point one can begin to glean the story behind the fracas. The two women are sisters: Teeni, as she calls herself—her family knows her as “Tina”—is dressed in tight jeans and a motorcycle jacket. She is the emotionally volatile younger sister who disappeared 11 years ago; she has picked this day to burst back into Sandra’s life.

Everything Between Us fits firmly into the family reconciliation genre, a formula in which layers of memory are revealed until, with the final revelation, the conflict is fully understood. But this conflict is set in an alternate world where the Good Friday Agreement led to the establishment of a truth and reconciliation committee in Belfast, in which perpetrators of violence and their victims on both sides are encouraged to fully confess their stories at a public forum. (The politicians of our world have never been able to agree to such a thing). Sandra is a member of the Legislative Assembly of Northern Ireland working with the committee. Teeni has just assaulted the South African facilitator, peppering her with racial slurs. The sisters are from a Protestant family with roots in the Unionist cause.

One may have to pardon Belfast playwright David Ireland for his conceits: a politician allowed to take an hour out of a major public tribunal in order to deal with a violent sibling? Wouldn’t Teeni have been arrested as a terror suspect, especially in a country that has a long legacy of terrorism? Why not have their reconciliation take place hours, even days after Teeni has been taken into police custody? Unfortunately, narrative contrivances are par for the course with two-handers. However, Ireland paints a vivid picture of how the microcosm of family dynamics weaves itself into the sectarian and nationalist ideologies that drove The Troubles. He is perceptive about how the trauma of these movements ruined families—as well as how families perpetuated various hatreds.

When artistic director Jason McCool moved to the Boston area, he established Solas Nua in Boston, a local branch of a Washington, D.C.-based organization that for a decade has been devoted to presenting contemporary Irish arts to American audiences. The parent organization has already staged Everything Between Us in Washington, Philadelphia, and Buffalo during its 2009/2010 season. Still, it may be a daring thing to present the Protestant side of The Troubles in Boston—in this predominantly Catholic area, stories abound about collections taken to procure weapons for the Republican cause. This is one of the benefits of presenting contemporary foreign drama to American audiences—it broadens perspectives. (The post-show talk back featured political scientist Robert M. Mauro of Boston College’s Irish Institute, who was there to discuss the political context.)

When Sandra was nine and Teeni was four, their father, a member of the Ulster Defense Association, the largest of the Protestant loyalist paramilitary and vigilante organizations (which often received intelligence from the British Army), was killed by the Irish Republican Army. Sandra’s experience has given her empathy for victims of Unionist violence; she has been working toward creating a new nation. Teeni, though born too late to have become a militant, carries on their father’s sensibility: a violent predisposition, alcoholism (she claims to have been sober for three years, but she exhibits the behavior of a “dry drunk”) and, despite her claims to be an atheist, her speech is laced with militant slogans and the language of sectarianism. She routinely uses “Fenian” as a slur against Catholics. Her sister chides her for racial slurs, but Teeni is unrepentant. What place does she have in the de-militarized society that has arisen in her 11-year absence in a country where Sandra shakes hands with Sinn Fein leaders and wears a green blouse with her black business attire? (In Northern Ireland, secondary colors could be making sectarian statements.)

David Ireland’s use of coded sectarian language helps him paint a vivid picture of the Belfast his characters call home. It’s not just Teeni’s slurs and slogans, but the stereotypes the women have of different neighborhoods and housing estates, the acronyms of the various armed groups that once roamed the streets. This ‘coded’ language (a dehumanized shorthand) illustrates how conflicts are articulated elsewhere and at other times, particularly when the characters use other hot spots as allegories for experiences closer to home, citing not just Apartheid-era South Africa but, perhaps not surprisingly, both the Holocaust and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These manipulations of shorthand, like caricatures and conspiracy theories, are useful evasions of truth and reconciliation.

Director Olivia D’Ambrosio’s noisy opening, the violence of its momentum, gives the play a robust energy that drove the presentation over the next hour or so. Reece and Gruttadauria created a clear sense of their characters even though they were still performing on book. Gruttadauria captured the off-kilter physicality of Teeni, whose hyper-sexuality and aggression have always led the way; her rationalizations inevitably following. Reece was more restrained as befitting her character, and her stage accent sounded as authentic to my American ears as Gruttadauria’s native accent, the latter having grown up in a small and mostly Protestant town outside of Belfast.

Solas Nua will be presenting eight more staged readings of contemporary Irish plays at The Burren this season.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: David Ireland, Everything Between Us, Ireland, Olivia D'Ambrosio, Solas Nua