Movie Review: An Unreal “Social Network”

So enough with the nostalgic wistfulness for a bygone era, the tears shed for a generation lost in cyberspace. The popularity of Facebook only serves to prove that we are more interested than ever in human contact.

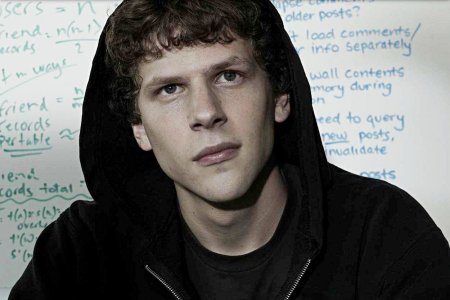

Jesse Eisenberg portrays Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. Is he the man who warped the social skills of a generation?

Reviewed by Justin Marble.

When reviewing The Social Network, I am going to start at the end. The final image of the film, and this is not spoiling anything, is Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, played by Jesse Eisenberg, on Facebook. He’s just sent a friend request and he’s sitting alone in a dark room hitting refresh, waiting for the other person to accept him back. It’s the only time throughout the entire movie that we ever see Zuckerberg alone.

Why is this? Because David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin, the director-screenwriter team behind The Social Network, never spoke to Mark Zuckerberg. Neither did Ben Mezrich, the writer of The Accidental Billionaires, the book that the film is based on. Everything that we learn about Zuckerberg is from the point of view of Eduardo Saverin, played in the film by Andrew Garfield, because Saverin was Mezrich’s main point of contact on the book. The rest of the film is “recreated” from a goo of court depositions, hearsay, and Sorkin’s own fanciful imagination.

According to the film, Saverin is Zuckerberg’s business partner and best friend who is ultimately betrayed by the tech wunderkind on his way to world domination. Of the main characters in the film, Saverin is the only one who comes across as likeable, far more compelling than the caustic Zuckerberg and the borderline comedy duo of the Winklevoss twins, a pair of Harvard jocks who sue Zuckerberg for allegedly stealing their idea.

Garfield plays Saverin with a vulnerability that simply doesn’t fly in the high-tech world, which favors the detached and somewhat cynical nature of Zuckerberg. But does it surprise anyone that he’s the most admirable character? He was the person who told everything to Mezrich—so obviously he’s going to make himself out to look like the good guy.

Mezrich’s publisher defines the book as “big juicy fun” rather than actual reportage, which is what The Social Network is. It’s big juicy fun. It’s gossip. It’s expertly directed by Fincher with usually-stellar dialogue from Sorkin. But it’s not true, and that undermines any point it tries to make.

We have a film about a person who was never spoken to filtered through the eyes of someone who ultimately ended up suing him for over a billion dollars (successfully). Yet somehow the mainstream film press has overlooked this because of The Social Network’s supposed relevance to the times we live in, because of the expert craftsmanship on hand, and because the film “perfectly defines this generation.”

Those are the words of Rolling Stone film critic Peter Travers, a man who I feel usually gets it right even though he has a penchant for whipping up bombastic blurbs in order to get his name on a movie poster. Travers isn’t the only one to make this point, but he’s the most high-profile and the one whose name is attached to all the posters and trailers. I make a point of avoiding reviews before I see a film, but Travers’s quote was unavoidable, and it stuck in my mind while I was watching it.

Here’s Travers on the final scene of the film: “The final image of solitary Mark at his computer has to resonate for a generation of users (the drug term seems apt) sitting in front of a glowing screen pretending not to be alone.” Again, in an article about movies that “defined generations,” he writes, “[the film shows] how technology is winning the battle against mutual human contact, creating a nation of narcissists shaping their own reality like a Facebook page. If youth can’t see itself in this movie, it’s just not paying attention.”

All right. Let me first point out the hypocrisy of 50-to-60-something, old film critics declaring that something defines a generation that they have little knowledge of. Because there are so few young film critics out there, this idea has gone unchallenged, but the very premise of Travers’s (and many other people, mostly older, have made this same point) argument is so inherently backwards that it simply must be addressed.

Travers pitches a battle between technology and human contact as if the two are mutually exclusive. All that time spent on Facebook must have turned us into a generation of socially maladjusted morons who can barely string a sentence together without an interjection of “OMG.” This is patently false. Facebook’s very premise is that people want to be accepted, that people want to interact with and to have contact with other people. That is the reason it’s a 500-billion-dollar company, and that’s the reason it’s spread beyond a bunch of college kids to pretty much everybody.

Facebook is a tool that we use, so it cannot then “create a nation of narcissists.” We filter what we want to be shown, yes, but this is not something that technology allows us to do. Human contact is artificial; we are adaptive creatures, and there are very few people out there who are so comfortable with themselves that they act the same way in front of every person they are acquainted with. We care deeply what people think, but this is not something that Facebook changed. It simply put it online.

Nobody thinks of the telephone as stifling human contact, so why does Facebook? The internet has introduced a number of conveniences that actually make human contact easier. If I’m organizing a party (yes, Mr. Travers, college kids still party—still have “human contact”—despite our techie upbringing), I don’t need to spend three hours on the phone calling everybody. Instead, I click a couple boxes. If I need to talk to my parents, my girlfriend, my brother, or anyone else, they’re usually a click away. What is so bad about this? What are you afraid of?

We no longer live in the days when people don’t leave the town that they were born in. The world is getting smaller, and everyone is becoming interconnected—we’re becoming a network. And by in zeroing in on the people who made this network rather than the people that populate it, The Social Network misses the point.

The film ultimately doesn’t make much of a point about anything because it is not set in reality. The events here are fabricate—Mezrich and Sorkin openly admit to this. The film will still make a gajillion dollars and probably win a few Oscars for being so damn buzzworthy because it’s superficially attached to the one thing that everybody now has in common and can relate to.

Here’s what the film, Travers, and Sorkin are all missing. Mark Zuckerberg didn’t create Facebook. It’s not as if Zuckerberg created this platform that then became self-aware and took over the world. It needed everybody else to jump on board. Facebook didn’t change us, it simply hit upon something that was always there.

So enough with the nostalgic wistfulness for a bygone era, the tears shed for a generation lost in cyberspace. The popularity of Facebook only serves to prove that we are more interested than ever in human contact. We are more aware of how others will perceive us. We are more enamored of what is happening outside of our own personal bubble. We are less inward and more outward, less private and more public.

And “shaping our own reality?” When has anybody not done this? Everything that we experience is filtered through our own perception. It’s the reason Mark Zuckerberg looks like a complete and utter jerk on the big screen. He’s seen that way by Eduardo Saverin, who told Mezrich, who told Sorkin, who told Fincher, who is now telling all of us. To get a true picture of a person is to truly know them. Facebook doesn’t let us peer into a person’s very soul, it’s true. But neither does it prevent us from carrying out the relationships we have had for millennias.

For one person to “define” another takes years of intimacy, and many people still get it wrong. That’s why The Social Network fails as a biopic of Zuckerberg, fails as a generational examination, and fails as anything other than something to enjoy while munching on some popcorn. To define a generation—billions of people, all with different backgrounds, hopes, dreams, and experiences—is impossible, and to argue otherwise is disingenuous.

In conclusion, let me quote one of your other films that “defined a generation.”

“You see us how you want to see us . . . in the simplest terms and most convenient definitions.”

That was 25 years ago. It’s still true today, and it’ll be true as long as people are talking and interacting with each other—having human contact. The world has changed. People haven’t.

If you can’t see that, Mr. Travers, you’re just not paying attention.

========================================

Here’s more information on some of the key discrepancies between the film and reality.