Stage Interview: Robert Scanlan on Samuel Beckett’s Women

“When we turn so crass and commercial that we have lost our way, Samuel Beckett will be rediscovered as the way back.”

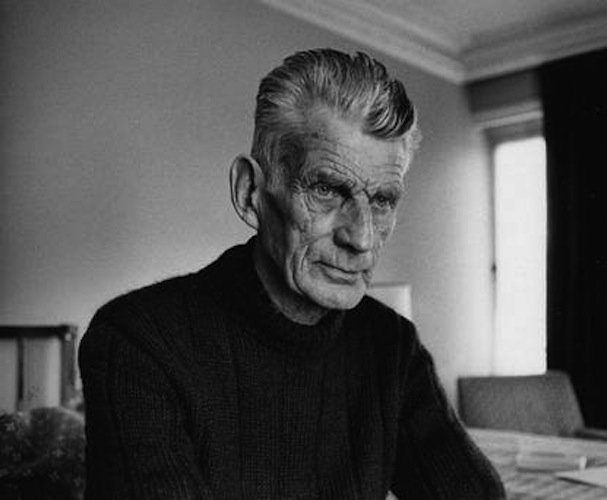

Samuel Beckett — “It is hard to characterize the feminine dimension of Beckett’s imagination.”

By Bill Marx

Men and women have poetic but problematic relationships in the works of Samuel Beckett. In his 1966 prose piece “Enough,” the female narrator refers to her differences with her mate of “Ten years at the very least”: “If the question were put to me I would say that odd hands are ill-fitted for intimacy. Mine never felt at home in his. Sometimes they let each other go. The clasp loosened and they fell apart. Whole minutes often passed before they clasped again. Before his clasped mine again.”

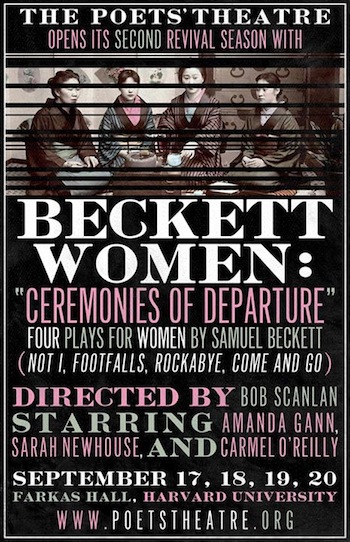

That notion of clasping and letting go, compounded by the uncertainty of whether that familiar touch will return, takes on mysterious resonances in Beckett. In plays such as Waiting for Godot and Endgame, the dramatist looks at how males lose their grip. But what about his women? The Poets’ Theatre is opening its second revival season with Beckett Women: “Ceremonies of Departure,” (September 17 through 20 in Farkas Hall at Harvard University), an evening made up of four powerful pieces (Not I, Rockabye, Footfalls, Come and Go) that focus on female voices bidding adieu. This unusual assemblage will no doubt reveal some interesting differences with how Beckett’s guys fade out, though the dramatist conveyed the crepuscular withdrawal of both genders with a gaunt but beautiful lyricism.

Poets’ Theatre Artistic Director Robert Scanlan has an impressive cast to work with: Sarah Newhouse, Carmel O’Reilly, and Amanda Gann. I sent him some questions via e-mail about the line-up of the plays and what, when seen together, they say about Beckett’s vision of the feminine experience.

Arts Fuse: Why have you grouped these Beckett plays in this configuration? Is it unusual?

Robert Scanlan: It was Sam Beckett himself who suggested this grouping. As you know, I knew him well during his last decade, and I asked him for permission to direct an all-women Waiting for Godot with a women’s collective in Belfast (Charabanc Theatre Company). I had become close to Charabanc after Tina Packer invited them to Boston, and I greatly admired their work. I was invited to Belfast to guest-direct the company, and it led to a close association with the Belfast playwright Marie Jones (Stone in his Pockets) which persists to this day. I asked Beckett for permission to stage Godot with Charabanc, and he felt compelled to say no. He did this in person on one of my visits to Paris, and he suggested an evening of plays he had specifically written for women, as a preferable alternative. He even suggested that the small play Come and Go, seldom performed because it is so short, would take on a completely different character if performed at the end of the other three solo pieces on the program. I am finally making good on this suggestion, which has remained in the back of my mind for a couple of decades.

AF: What is Beckett’s vision of women in these plays? How do these ‘ceremonies of departure’ differ from the farewells of males?

Scanlan: They are closely linked to mothers. Mother-daughter relationships stand out in two of the plays. Also friendship and solidarity. It is hard to characterize the feminine dimension of Beckett’s imagination, but his own mother, May Beckett (a difficult woman) can be discerned pretty clearly. All three of the solo pieces portray isolated characters coping with the approach of the end. If I contrast these figures with men in similar Beckett situations (Eh Joe, Endgame… ) I would say that the men have a tendency to be meaner, more irascible, less patient, to have a diminished capacity for endurance. But you have forced the question. I have not been conscious of the distinction as we work. What was clear is that Beckett could not envision women as Didi and Gogo in Godot. That remains baffling. The Charabanc women took offense and refused the alternative programming, which is why I am only getting around to this grouping now. It has its own deeply anchored integrity.

AF: Beckett and the Poets’ Theater have a long history. Why is it important for the organization to stage these plays now?

Scanlan: In my case, Beckett’s work is a signature of my career in the theatre. “Ceremonies of Departure” (the subtitle I have given the grouping of plays) clearly captures a common thread among the four plays. My own mother died just last year at the age of 99, and I was there at the mysterious transition. I am also leaving Harvard after teaching here and helping develop a strong undergraduate degree component for 25 years. Beckett sent The Poets’ Theatre several texts over the years. One of our founders, the incomparable Mary Manning Howe, (director of Radcliffe’s theatre program) was a close childhood friend of Beckett’s and even arranged, in the 1930s, an offer to teach in Harvard’s English Department (he declined by not responding). In the year of his death, Beckett handed me a copy of the typescript of Stirrings Still with instructions to bring David Warrilow from Paris to perform it on what turned out to be Beckett’s last birthday. This we did at the Museum of Fine Arts, where I hope to revive a close association once again for the revived Poets’ Theatre.

AF: What are the challenges for the actresses in performing these pieces together?

Scanlan: I am uniting the three actresses on a stage we are treating as a sort of temple, with Asian motifs I have brought back from a life-changing trip I made to Vietnam last March. This trip was itself a direct outgrowth of a Poets’ Theatre offering: The Word Exchange: The Music of Poetry in Translation. In that evening, I included a section in which Vietnamese poetry was featured, and this lead directly to an invitation to Hanoi, and contacts there we hope to develop into future exchanges and performances. There is a Temple of Literature in Hanoi, where a reverential atmosphere deeply impressed me. I want the Poets’ Theatre to be a local “temple of literature” in a similar way (fond wish!). So in addition to performing with deep concentration roles steeped in difficult text (a strain on memory) and in difficult thoughts (loneliness and death) my actors have to be “present” as temple attendants between the plays. They never leave the space, until the end. They witness each other’s performances, and are united in the final play. The whole evening of four plays is a single long “service” that David Gammons and I are staging with extreme care and attention to detail.

AF: Any trepidation at being a male directing this evening?

Scanlan: None until you asked. I belong to the school of “transparent directors,” who try to disappear from the final event. I have worked with and known the women in this cast for many years. Two were once my students, but are now well over me. Their own artistry is carrying the full burden of the plays, and I trust them, as I trust all women, to carry the feminine into visible being. For years I have used a “Locus of Being” analysis to understand how Beckett’s works are composed. My own “locus of being” is not a conscious feature in my service to his plays. And no, I direct these plays no differently. I do think, however, that they convey a a context that would be appropriate to a theatre that was focused by design on feminine experience — say the Nora Theatre Company. Perhaps they should have an extended run there, under that wonderful theatre’s auspices and authority.

AF: Modernism has largely gone out of fashion in the theater — the emphasis now is on the easy-to-take messages of musicals and political empowerment dramas. How is Beckett’s work faring?

Scanlan: We’ll see. Who cares what the fashionable label may be at any one moment. I work the other end of the aesthetic spectrum. My faith is that whenever we get too far away from cultural manifestations as rich and deep and full of meaning as Beckett’s work is, the pendulum swings back. I have many young people working with me on this production, and I can see them opening up with relief and wonder to the depth and seriousness of this work. Beckett is for the long haul. He burst on the scene at a bad cultural patch in America and inspired a whole generation of “avant-gardistes.” When we turn so crass and commercial that we have lost our way, he will be rediscovered as the way back. That is also the mission in Cambridge and Boston (and soon, Internationally) of the resurgent Poets’ Theatre. As Richard Wilbur, one of our original founders said to me last year, “we were formed with a vengeance; don’t lose that edge.” My Beckett Seminar was always a “life-changer” for my undergraduates. I have never seen that hope diminished. Come see what I’m talking about. My deepest loyalty to Beckett is in my work onstage.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Amanda Gann, Beckett Women: Ceremonies of Departure, Carmel O'Reilly, Come and Go, Footfalls, Not I, Robert Scanlan, Rockaby, samuel-beckett, Sarah Newhouse

I hope I get a chance to see this program as Not I is a particular favorite of mine amongst the Beckett corpus.

Theatergoers will get another opportunity to see Not I performed by the incomparable Lisa Dwan from the UK when she holds forth at ArtsEmerson in Boston for a performance that includes Footfalls and Rockaby, March 16-20, 2016.