Fuse Book Review: “Wilde in America” — Not Wild Enough?

What Oscar Wilde was peddling in America was beauty. Art for art’s sake. Gorgeous flowers. Ravishing colors.

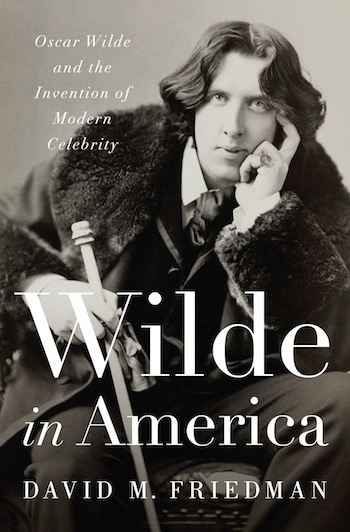

Wilde in America: Oscar Wide and the Invention of Modern Celebrity by David M. Friedman. W.W. Norton, 320 pages, $26.95.

By Gerald Peary

I’d been aware that Oscar Wilde did a popular speaking tour of the USA, but I’d always assumed he came here to tout his plays, his poems, and The Picture of Dorian Gray. The surprise of David M. Friedman’s Wilde in America, for those like me who haven’t read earlier Wilde biographies, is that Oscar triumphed in America before he’d done anything much at all. Post-Oxford, he’d attended a lot of high-end London parties. No play had been produced, and his one book of verse, Poems, was self-published, a vanity press item from the most shamelessly vain of 27-year-olds. And if he was renowned for his devastating wit, the wit was confined to informal conversation. Before being invited to America, Oscar Wilde had never delivered a formal lecture in his life.

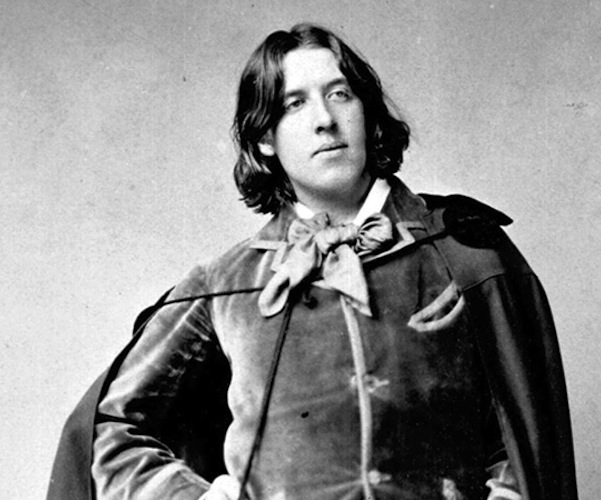

Why he was offered this tour is still hard to fathom, though Friedman tries to explain it in the book. In London, attention was paid to this young man with the outlandish clothes, the floppy locks, the flagrantly effete mannerisms, and a well-practiced stream of pithy, pre-Warholian epigrams. He was so well known, and so divisive a public figure, that W.S. Gilbert parodied him in his play, Patience; or Bunthorne’s Bride. Bunthorne was based on Wilde, with uncut hair, with “a poppy or a lily in his hand.” According to Friedman, the young post-graduate embraced the idea that all publicity is good publicity, He saw the London production several times, seemingly enjoying the joke on him. And so the play’s enterprising producer, Richard D’Oyle Carte, conceived this idea, which would work smashingly. Send Wilde to America, and coordinate his talks with an American tour of Patience. If people saw Wilde, they would be curious to see Patience. If they saw Patience, they would pay up to hear Oscar Wilde.

He arrived from England in 1882, held forth first in New York, then crossed and crisscrossed the USA for ten packed months of train travel, speaking engagements, and endless newspaper interviews. Woman adored him, he-men were revolted by his swishy demeanor. He ventured into 150 cities. In the process, says Friedman, the would-be writer became, for the American public, the most famous living Brit after Queen Victoria. Again, this was many years before, the substantial triumphs of Lady Windermere’s Fan, The Importance of Being Earnest, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, etc.

As Friedman never tires of telling his readers, Wilde was famous for being famous. It was his conscious game plan to be a celebrity first and, later, to parlay that celebrity into opening doors for his talents. Fame made it far easier to become an applauded playwright, a lionized novelist, an extolled poet. And to have champagne, oysters, steaks, and money. And tasty acolytes. In Friedman’s view, Wilde was the very first to succeed with this startlingly modern attitude:

Decades before Norman Mailer, Wilde knew the value of “advertisements for myself.” Decades before Warhol, he saw the beauty in commerce and the importance of image in marketing. Decades before Kim Kardashian, he grasped that fame could be fabricated in the media.

What Wilde was peddling was beauty. Art for art’s sake. Gorgeous flowers. Ravishing colors. A home as a work of art. Clothes as a work of art. YOU as a work of art. As Keats, his favorite poet, had preached, that’s “all you need to know.”

The best part of Wilde in America occurs before America, Friedman’s preparatory chapters. These demonstrate how Oscar Wilde, The Aesthete, was consciously developed, nursed, nurtured, checked in the mirror, polished. His choice of persona seems to have its source in the Dublin soirees of his mom, Lady Jane Wilde, which Oscar attended as a brash, spoiled teenager. Lady Wilde entertained Ireland’s poets, politicians, students with lively chitchat and lavish costumery. Here’s an admiring description by Irish writer Henriette Corkran:

Her long, massive face was plastered with white powder; over her blue-black glossy hair was a gilt crown of laurels. She wore white kid gloves, held a scent bottle and a fan. On her broad chest was fastened a series of large brooches…. This gave her the appearance of a perambulating family mausoleum.

Like mother, like son. A rejection of the drab Victorian world for flamboyance. Style. Speaking out. Strutting your stuff. “If I were alone on an island and had my things,” he said, “I would dress for dinner every night.”

With a spiffy new wardrobe, Oscar left Dublin for Oxford, where he filled his room with blue china, waxed on about pre-Raphaelite paintings. And–what synchronicity for his developing sensibility!– he took classes with the great theorist, John Ruskin, Slade Professor of Fine Art. Friedman: “Wilde was awestruck by Ruskin’s talks on the meaning and power of beauty, lectures that seemed more like public ecstasies than podium presentations.”

Oscar Wilde — Even Americans were capable of beautiful homes, comely appearance, if they heeded Wilde’s advice.

It was Ruskin’s aesthetic, including Ruskin’s rhapsodizing about color and his embracing of the decorative arts, which Wilde carried on when traveling through the USA. It informed his oratory. Even Americans were capable of beautiful homes, comely appearance, if they heeded Wilde’s advice.

What to say about the bulk of David Friedman’s book, taking us from one American city to another? The writing is good enough, but the story gets boring. The lectures blend into each other, and each town seems like the town before. And what Friedman catalogues each time is similar: how many people showed up for Wilde’s talk, how well it was received, what hotel did Wilde stay in, and who interviewed him for the press. Even Wilde’s meetings with famous literary personages—Henry James, Walt Whitman, Henry Longsworth Longfellow— have very little spark. What Friedman ultimately is missing, and what makes him an odd Wilde biographer, is proper bemusement. A show of ironic wit.

I confess. As Wilde in America chugged along, I kept wishing that Oscar would pack his bags and go home to England. Or at least have a sexy, raunchy night on the town. However, there seems no evidence that he did much cruising in America, remaining chaste and, perhaps, still virginal. It was only years later, when Wilde feasted among the young men of London, that he let out that, back in Camden, New Jersey, Whitman had kissed him on the mouth.

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of 9 books on cinema, writer-director of the documentary For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess