Fuse Book Review: The Subdued Yearning of “Guys Like Me” — The Sad-Droll Prose of Dominique Fabre

Very little happens in Dominique Fabre’s books and what does happen is rather unexciting, yet one keeps on reading because his depiction of ordinary human beings caught up in the routines and minor mishaps of daily life so genuinely reflects the lives that most of us lead.

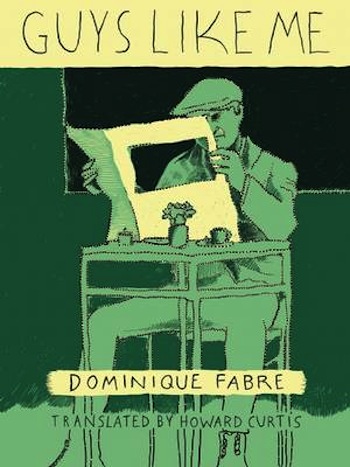

Guys Like Me by Dominique Fabre, translated by Howard Curtis, New Vessel Press, 144 pp., $15.99

Photos volées by Dominique Fabre, Éditions de l’Olivier, 313 pp., 18.50€

Des nuages et des tours by Dominique Fabre, Éditions de l’Olivier, 148 pp., 16.00 €

By John Taylor

The French novelist Dominique Fabre (b. 1960) has a tone. Open any of his novels and it can be heard. A colloquial melody both sad and droll, discreet yet somehow spirited. One can add: modest, warm, rather talkative, soliciting one’s attention but rarely revealing innermost thoughts entirely.

This latter quality especially creates the touching quality of his writing as well as its low-key suspense. Suspense? Very little happens in his books and what happens is rather unexciting, yet one keeps on reading because his depiction of ordinary human beings caught up in the routines and minor mishaps of daily life so genuinely reflects the lives that most of us lead. I cannot help but think of Henri Calet (1904-1956), with whose novels about working-class Paris Fabre’s own novels set in the French capital have affinities. At the end of Peau d’ours (1958), Calet notably quips: “Don’t shake me. I’m full of tears.” Similarly, whenever feelings start brimming over in Fabre’s novel Les Types comme moi (2007), now engagingly rendered into French by Howard Curtis, he inserts the phrase “Do you mind if I pull down the curtain?”

Guys Like Me tells the story of three middle-aged friends, Jean, Marc-André (alias “Marco”), and the narrator. They hail from La Garenne-Colombes, a drab suburb located northwest of Paris. This suburb is neither one of the impoverished, unemployment-ravaged districts found in other, northern, outskirts of the metropolis; nor is it similar to the ritzy residential suburbs also located west of Paris but further to the south from La Garenne-Colombes. Fabre describes an area with no particular reputation whatsoever. Moreover, it is undergoing urban renewal. The once-suitable, now-rundown apartment buildings where the three men had been brought up are going to be razed.

Since their childhood in La Garenne-Colombes, two of the characters, Marco and the narrator, have moved around a bit, fallen in love a few times, had wives and then divorced, and eventually fallen back into love—well, more or less. Marco has a second wife, Aïcha, and the narrator is slowly but surely (more slowly than surely) getting involved with Marie, a woman whom he has met by chance on an online dating website. Their story will take on, if no feverish romantic intensity, increasing seriousness when she is diagnosed with breast cancer. Questions about attachment and responsibility take shape, and the man and the woman cannot avoid responding to them. Almost despite themselves, they start coming face to face with each other.

But let’s return to the beginning. As the novel opens, the narrator has had a job, lost it, been out of work for two years, but again has an office job that mostly suits him. From his broken marriage, he has a son, Benjamin, who is now in his twenties and to whom he is attached. The narrator is even, in subtle ways, somewhat emotionally dependent on his son, a bright young man who, because his career is stagnating in France, will eventually emigrate to Switzerland to work in a laboratory in Zürich. The “brain drain” and other socioeconomic issues currently debated in France are woven into the plot, yet in no obtrusive manner.

Until his encounter with Marie, the narrator has been left, after flings and short-lived relationships, somehow relieved to be a bachelor and dissatisfied at being deprived of companionship. This attitude is typical. Most of his feelings are ambivalent. “I don’t trust my emotions,” he admits at one point, “because of my solitude, because of my job, because of everything and nothing, both together, all mixed up.” If he secretly yearns for something, he never does so overtly. He has long quietly aspired to buy a motor scooter, for example, but he keeps putting off the purchase. It is his son who, by presenting him with an amusing and poignant little gift, prods him into taking the first step. This father-son theme, which also comprises the narrator’s relationship to his own father (whom, by his own admission, he “hadn’t known very well”), crops up often, as it does in several other novels by Fabre.

Hesitation and haplessness define the “guys like me” with whom the narrator identifies. They are moderate losers and average has-beens and ordinary daydreamers all at once. In fact, the title of the novel also provides a recurrent phrase. When the narrator meets Marie for the first time, in real life, in a café on the rue de la Chaussée d’Antin, he characteristically uses the phrase to generalize upon his own predicament:

I paid for our drinks for our drinks and she got up while I was doing that and went downstairs to the toilet. I watched her, she was well dressed, in black with a white blouse. Her hair was black too. She wore lots of bracelets. Would it have been hard to say what she did for a living? She looked a lot like her photo on the website. Would we see each other again? I’d had enough of all those dates that never lead to anything, as if after a while, for guys like me, there’s no tomorrow.

Fabre has an artfully rambling style, employing stream-of-consciousness, inserted conversations, finely observed details, and sundry speculations. These disparate stylistic elements thus form a complex literary mix, yet the diction remains close to the spoken language. Consider, for instance, how the above café scene continues, both in so-called objective reality and in the narrator’s mind, that is, both as the scene unfolds (in a “present” recounted in the past tense) and as the narrator looks back on the same scene from another “present” that corresponds to his telling of the story. The abrupt shifts in time might have been confusing but they are not:

I looked at the customers in the café. The waiters, the high school kids, you often saw them laughing and smiling, how to take my place among them again? I wanted to make love with Marie. I remember very well how much I wanted that, standing there on the sidewalk, on Chaussée d’Antin. Without doing it deliberately, I looked at myself in the mirror at the end of the room, wondering if it was still possible for a woman to want to wake up in bed with a guy like me the following morning. How are you? Did you sleep well? Yes, how about you? Tea or coffee? For years and years. I had to remember not to let myself go when I was with her. When she came back, I saw she’d taken the time to touch up her lipstick. I was pleased about that, though I couldn’t quite say why. We talked a little more, smiling at each other, and at the corner of Rue du Havre, after all those hours talking online, I felt like kissing her.

Fabre often jolts time frames or perspectives like this, in the middle of a paragraph, suppressing transitions not only to liven up what is, once again, quite commonplace subject matter, but also to mirror non-continuous flows of thought and feeling. Flashbacks occur often. Now and then, the author alludes to books by F. Scott Fitzgerald, less for the social milieus that the American author dissected than for his characters grappling to get a hold on their lives. While Marie is undergoing chemotherapy and wants to spend time reading between sessions, the narrator lends her his collection of Fitzgerald novels: “She’d made a face at first because he was American and these days too many things in life were American, but in the end she liked his work. Tender is the Night. It isn’t always like that.”

Another engaging weave in this intricate novel concerns Jean. The narrator runs into him on the street. They have been out of touch for years. Jean is out of work and vaguely looking for some kind of employment. Actually, it is the narrator who encourages him to land a job, which he manages to do when Marco intervenes as well. But Jean ends up wandering away from it. His colleagues find him difficult to get along with and he isn’t really interested in working, anyway. Yet he is not without talent. He has lived in Germany and knows the language. When the narrator gives him a German translation to do, as a means of supplementing his welfare checks, Jean complies, but when he finishes the job he neglects to send in the invoice.

A sort of passive anti-hero, Jean is mostly a harmless burden for the two other men. They put up with him; such are childhood ties. Yet even as Fabre gives nuance to their personalities and especially to the narrator’s, disclosing hidden weaknesses and not yet completely diminished inner resources, he draws out unsuspected depth in Jean as well. He has a somehow intriguing attachment to and dependency on his mother, who has relocated to Marseille and is in the initial stages of Alzheimer’s. He still lives in La Garenne, for the time being (though he will eventually move to Marseille), and thus represents the past. His collection of photographs from his teenage days provokes slightly disturbing memories in Marco and the narrator. (Another quotation by Henri Calet comes to mind: “The past crumbles once you stick your hand in it.”) At a dinner together, Jean, who despite his laziness is actually quite loquacious, comes to talk about his lost first love, Adeline Vlasquez. Here is the narrator’s report on the couple:

They’d set up house together, they were lucky and even found a little house on the hill at Puteaux at the beginning of the ‘80s, before the property boom. They’d made plans for the future, and then, without warning, that fatigue of his had struck again. He’d had to quit his job. She thought he was doing drugs, or that he was cheating on her, she thought a whole bunch of things, and in spite of his efforts she ended up becoming tired of him, she’d left him two years after the election of François Mitterrand.

The narrator then reflects: “He’d been telling me the life story of a guy like me, when it came down to it, but one where every episode took place between attacks of what he called his fatigue.” In fact, nearly everyone in the novel suffers from some kind of “fatigue.” Yet this fatigue notwithstanding, they will all, unexpectedly, spot glimmers of reassuring outcomes at the end.

The reader might first think that Fabre is going to fill out Jean’s story in Photos volées (2014), which has just appeared in France. The narrator of that novel is also called Jean, but he is another Jean who is involved, to various amicable and amorous degrees, with women different from those who were the minor characters of Guys Like Me. Here the protagonists are named Élise, Nathalie, and various “Hélènes,” one of whom is the narrator’s ex-wife and another his lawyer. However, some of the same Parisian quarters and outlying suburbs are conjured up. And there are other similarities.

The Jean of Photos volées—literally “Stolen Photos”—works in an office in the Chaussée d’Antin area, as did the narrator of Guys Like Me. Now that he is 58 years old, the firm is trying to get rid of him before the legal retirement age (60). In France, employers must sign a “contract of unlimited duration” with their employees, a tenure status that prevents them from being fired or laid off except in a few precisely defined situations. Yet management sometimes contrives methods of getting elderly employees to leave on their own, ahead of time, so that they can be replaced by young newcomers with starting salaries. Subtle, and less subtle, forms of harassment are employed. When the employee can no longer stand what his work environment has become, he agrees to a financial settlement and resigns.

Such pressure is put on Jean when he is ordered to give up his office space and to update old files in the “archives.” He ends up consulting a lawyer, Hélène, in order to see what can be negotiated. In her office, he watches her search for his file in a big “closet behind her, with probably lots of other guys like me inside, men and women worn down by all the means used by life to defeat us.” There are those “guys like me” again.

French author Dominique Fabre — he has an artfully rambling style, employing stream-of-consciousness, inserted conversations, finely observed details, and sundry speculations.

Photography was a minor theme in Guys Like Me. Here it becomes more important. Before working in the office, Jean was an independent photographer for twenty years, and during this time he did not always pay his contributions to the Social Security retirement plan. He would need to work several more years in the office to catch up and acquire a suitable pension. Although he will be unable to do this, modest surprises nonetheless await him in this similarly touching tale of subdued yearning.

Like the novelist Patrick Modiano (b. 1945) and the poet Jacques Réda (b. 1929), Fabre is definitely a “pedestrian of Paris,” as Léon-Paul Fargue (1876-1947) phrased it. He knows the city, especially the non-touristic quarters, like the back of his hand. To wit: another recent book, Des nuages et des tours (2013). The title means “Clouds and High-Rises.” This sensitively penned personal essay mostly explores the thirteenth arrondissement, much of which started becoming the Parisian “Chinatown” during the 1980s (when I was myself living there).

In Fabre’s novels, chance meetings take place against a backdrop of everydayness. And I also experienced such an encounter while reading this gently absorbing book, to which I am also grateful for bringing me up to date on neighborhoods that I have not strolled through for years and sometimes decades. How delighted I was when I arrived at page 88 and ran into an old friend, the detective-novel writer Alain Demouzon (b. 1945)! As a way of finishing this article, let me translate the passage. It not only pays rightful tribute to Alain’s knowledge of all sorts of details—which then appear in his own mystery novels, distinguished for their sensitivity and verisimilitude—but also points to the same “fragile feeling of eternity” that Fabre’s narrators most secretly, most deeply, search for:

I met Alain (Demouzon) below the Melville Public Multimedia Library. He was bringing back some books. We chatted. He had debarked in the arrondissement in 1971, before the massive arrival of Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees who took over the high rises where native Frenchmen didn’t want to live. He spoke to me of the Kobushi magnolia at the corner of the rue Nationale, and then about the other trees in the neighborhood, various prunus trees with complicated names—he can name them all. He spoke to me of the municipal gardener who worked there before the one I knew. About restaurants, before they became Chinese. . . His visions of the quarter could surely include a black Bentley parked in front of a bronze-colored brick apartment building. Sometimes all this gives you a fragile feeling of eternity, while real time keeps bumping along nastily (nothing to do with a tour in a Bentley) down the rue du Château des Rentiers.

John Taylor is the author of the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction, 2004, 2007, 2011) and, most recently, A Little Tour through European Poetry (Transaction, 2014). He has translated books by several French poets, including Philippe Jaccottet, Louis Calaferte, Jacques Dupin, and José-Flore Tappy. Forthcoming from Seagull is a new translation, Georges Perros’s Paper Collage. His most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012). He lives in France.

Tagged: Dominique Fabre, French literature, Guys Like Me, Howard Curtis, New Vessel Press