Arts Interview: Scott Timberg Looks at the “Culture Crash” Square in the Eye

“For the thousands and maybe millions of us who’ve lived through this mess – who’ve seen the consequences close up – it’s not depressing to be told that writers and artists are getting screwed. It’s our daily reality.”

Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class by Scott Timberg. (Yale University Press, 320 pages, $26)

By Bill Marx

Scott Timberg’s Culture Crash is a valuable book because it describes the plight of American arts and culture as an ecological catastrophe, a disaster rooted in the conquest of a trickle-down mentality, intellectual as well as economic. It is not just a matter that most artists, from musicians and architects to writers and film makers, are being asked to market themselves more in order to earn less. It is about the end of used book and record stores, the shrinking of journalistic arts coverage, the dearth of independent criticism, and the triumph of the ethos that bigger-is-better. These changes are not just the result of the last recession. According to Timberg, a former arts reporter for the Los Angeles Times, we are witnessing a transformation: a downsizing of our cultural capital generated by “anti-elite rage, market populism, and corporate consolidation.” The creative class is being exploited rather than supported — by its supposed ‘friends’ as well as its enemies.

Yes, as Debra Cash points out in her smart review, there could be more analysis and fewer anecdotes in Culture Crash. For my money, there is not enough on the decimation of arts education and the systemic exploitation of the under-class. There is too much on the value of middle brow culture and the soul-sapping relativity of post-modernism. And there are too many humbug arguments about the perniciousness of the web (media giants and corporations demand free content because they can get away with it, not because technology makes them do it). Still, even if you don’t accept all of Timberg’s theories about who is putting the squeeze on creatives, this book should be read by anyone in the world of culture who wants to peer beyond the profitable illusions of middle class contentment touted by our various snake oil salesmen, from Richard Florida to universities, the mainstream media, and arts organizations. As the lemmings gallop toward the cliff, shouldn’t they at least get a good look at the approaching abyss? Culture Crash provides a passionate look down at the future.

I was filled with questions after reading Culture Crash — from why the struggles of the creative class have garnered so little attention to how the dumbing down of criticism has contributed to the cultural decline. I e-mailed Timberg and he sent back some splendidly detailed responses.

Arts Fuse: Why do you believe that the media, universities, and cultural institutions have neglected talking about the crisis for the creative class?

Timberg: Indifference, blindness and passivity are hard to figure out and describe. I’ll try to be succinct.

In the nastiest months of the economic collapse – which is one important event in my book – everyone, including the press, was concerned that the U.S. and even the world economy would topple in a way that would make 1929 look like a bad ferry ride. The plight of musicians and scribes didn’t really come up.

And when we caught our breath, many people – including editors – were looking for “good news” stories, or “counter-intuitive” stories. I had at least one editor tell me she was not interested in a story about what it was like for an educated middle-class person to lose his job and house, unless it was a layoff-was-the-best-thing-that-ever-happened-to-me story. You saw a lot of pieces about people set free to pursue their “Plan B.”

We differ on a lot of things, but Americans on the whole love optimistic tales, happy endings, Horatio Alger stories, etc. We consider a hard look at reality “wallowing,” “whining,” etc. It’s not just Americans; we call these uncomfortable truths for a reason.

As for ignoring the creative class in general: There’s good-old American anti-intellectualism and the centuries-old notion that an artist is not really “one of us,” that they are some seditious or anomalous tribe. Not unique to the U.S. but Newt Gingrich, Dan Quayle and others doubled down on this idea with the term “cultural elite.” (You could be a billionaire banker in a gated community and call a newspaper reporter or abstract painter an elitist.)

Universities are full of smart people. But most of them, even the artists and musicians and writers, don’t make their living from their creative work – they get a salary based on teaching – and those with tenure are even more insulated from the realities of the creative economy. So you get a lot of nonsense coming out of communications departments, business schools and law schools saying, Let’s dismantle copyright to liberate creativity. Or, Musicians need to stop complaining and start “adjusting,” etc. Real easy to say when a paycheck arrives every two weeks and your medical insurance is covered.

Another institution that failed here was the White House. I consider Obama a vast improvement over George W. Bush, and this supposed African socialist has been far better for capitalism than his CEO predecessor. But his housing policy – and lack of guts dealing with the banks which held mortgages and helped create the crisis – was pathetic and lame. People like me, who’d worked their whole lives, made frugal decisions, had maintained good credit, were left to twist in the wind. The banks got bailed out with our tax dollars, their execs got bonuses, and for me and many other musicians, artists and writers who lost their homes, all of our wealth was destroyed.

Scott Timberg — “The people responsible for passing down the value of art lost their nerve, or their faith.” Photo: Steven Dewall.

AF: The subtitle of this book could be “The Killing of Middlebrow Culture” — who did the deed and why should we care?

Timberg: A lot of what my book describes involves unintended consequences, and I think this is what happened here. This is a place where I never intended to end up; I was once a Wesleyan English major besotted with postmodern literature, experimental music and French theory, so I had to go against a lot of my instincts to see that it was the middle, not the edges, that needed restoring.

But in a nutshell, the people responsible for passing down the value of art – humanities professors and culture critics, for example, and media-savvy artists like Warhol – lost their nerve, or their faith. The priesthood stopped telling the flock that art was sacred or transcendent or a path to wisdom, and began calling it sexist, built on hegemony, a formation of cultural capital, an endlessly deferred signifier, etc. Some of this was true, at least in part. I don’t want to sound like Bill Bennett or Lynne Cheney and reject it all. But there was a price to be paid in the longterm for this.

And this overlapped with a movement going back to 19th century Paris – romantic bohemianism – which separated art from the marketplace and divorced the bohemian from the bourgeoisie. A lot of great art and poetry comes from that period. But all this stuff has consequences.

One writer who brought me around to seeing all this, by the way, was David Foster Wallace.

AF: The meaning of middlebrow is a bit slippery in the book — it includes indie rock. Unlike Dwight Macdonald, I want middlebrow art to exist — but do I have to like it?

Timberg: Middlebrow has always been a complicated/ ambiguous concept – or set of concepts – and I may have done it no favors here.

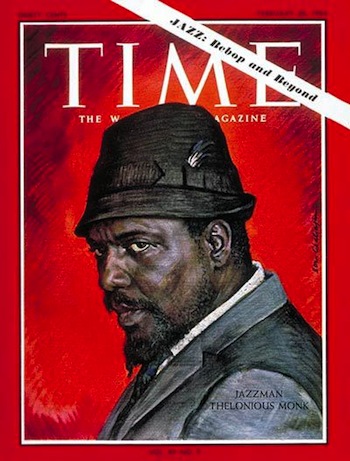

When I lament the loss of middlebrow, I’m not saying I want nothing but overplayed warhorses at symphony orchestras, nothing but Matisse shows at the museum, etc. What I miss is the notion that art is somehow clarifying or restorative, and that a broad public education and media push is worth investing in. Middlebrow means Leonard Bernstein on TV, Thelonious Monk on the cover of Time, Anne Sexton learning how to write a sonnet on public television, Lionel Trilling and Auden leading a book club for non-scholarly readers, public school art classes, etc. It says there’s something valuable about culture that goes beyond money (what the neoliberal or capitalist values) or shock value (what much of the cultural left values.)

Middlebrow, whatever its fault and blind spots and earnest pieties, values literature and the arts as aspects of human achievement.

Don’t think indie rock is really middlebrow in any way, but I included it in that section about “Restoring the Middle” because it (like indie film) is built on mid-size budgets and a middle-class audience. If you say you like, say, the films of Spike Jonze and bands like Pavement or TV on the Radio, your taste may have a bit of the avant-garde in it (or what we called in the ‘90s “cutting edge”) but economically, they are in the middle. (That is, they are neither blockbusters nor micro-finances shoestring operations, both extremes which have grown in the 21st century.)

And, no, you don’t have to like it. (I often don’t.) It’s about an ecosystem, not any of the individual flora and fauna within it. When it dies, everything around it starts to wither.

AF: Isn’t the danger less about the disappearance of middlebrow art and the spread of uni-culture — everybody likes what they like and it is all the same … no distinctions among high, middle, or low required.

Timberg: It’s funny that you use that phrase, “the uni-culture,” because the populist critics who call themselves the Poptimists – who I liken to a Tea Party of criticism – talk about the old world as a dreary, lockstep “monoculture.” (They say a thousands niches have now bloomed.)

I used to write enthusiastically about the breakdown of categories and hierarchies and boundaries. We have to acknowledge that, say, the detective novels of Ross Macdonald and the science-fiction of Ursula Le Guin have literary content. Or that the Delta blues of Son House is in some ways deeply serious music. Godard and Tarantino have made something complex and lyrical, at least some of the time, out of gangster films and martial-arts movies.

But when we then start saying a manufactured pop star like Lady Gaga is an important cultural figure who has to be reckoned with in countless think pieces, the postmodern turn has gone too far. Similar with Jeff Koons – just because he shocks people doesn’t mean he’s the new Duchamp or Picasso. He’s just a cash register with a wiseass smile.

AF: One of my favorite sentences in Culture Crash is “With the cultural and psychological triumph of the market, we’ve lost the very language by which we express the worth of things.” Has there been a special animus against serious criticism in the decimation of the American arts economy?

Timberg: I’m glad that resonated with someone! But I don’t think it’s an animus, exactly – more indifference or the sense that critics are just a bunch of gloomy naysayers. (“Why be negative?”) As a lot of people in the arts and music – especially people younger than me – embrace the market and popularity and “going viral” and all that wholeheartedly, there’s a sense that criticism needs to serve the marketing plan or it’s just in the way. (And can it be reduced to a number or score?)

We live in an age in which Ayn Rand and market worship are taken serious by people who are beyond their sophomore year of college, some of whom have powerful jobs in the U.S. Capitol. Is it any wonder that critics, who tend to mediate the marketplace, are considered irrelevant killjoys?

Assembly line pop star Lady Gaga — an important cultural figure?

AF: You examine the rise of consolidation (the big get bigger) and the race to the bottom in the arts economy. But not the collapse of arts education — how important a factor has that been in the killing of the creative class?

Timberg: Very, very serious. I would have written a whole chapter on this if I’d had the time and space. Things won’t get better until arts education in public schools is restored.

AF: Advocates for the arts often use an economic argument for its value — that the arts generate enormous income for local businesses and encourage tourism. Why hasn’t that wealth trickled down to the creative class?

Timberg: Well, very little has trickled down to anyone. When corporations and rich people hold all the cards, it bad news for the middle-class, a place where most of the creative class lives (despite their protests.)

The Internet was supposed to make a new avant-garde possible, to liberate creatives to connect with their audiences directly, etc. It’s worked out for a few. But the Web is more and more corporate controlled every day – why should they give up any of that dough if they don’t have to?

Especially when you get the ideology of “free” – give your work away for the “exposure” – it’s not gonna end well for the writers or musicians or graphic designers. But if you work at Google or Amazon or Facebook or Spotify, it’s a blast. And there’s free sushi in the cafeteria

AF: Artists, arts journalists, academics, and editors have contributed, in some cases eagerly, to their extinction by turning art and cultural journalism into marketing. How can that be turned around?

Timberg: You know, there’s this old idea that artists somehow set the social and political agenda for a society – “the unacknowledged legislators” argument. In some ways it’s true; look at fashion and sexual mores. But on this one, I think it may be a bit late to put the genie back in the bottle. Unhinged capitalism has won – psychologically and otherwise.

If there’s anything the creative class can do to turn back market worship, it’ll take a while.

AF: You mention public radio, but not how it has contributed to the culture crash. On the one hand, you could argue that it generates the kind of middlebrow culture you think is valuable. Yet when it comes to paying journalists and critics to cover the arts it is as bad as newspapers and magazines. Is NPR part of the solution or part of the problem?

Timberg: All true. But I don’t see any reason to single out public radio for lowballing creatives – everybody’s doing it these days. NPR could probably pay them better if it was more robustly funded.

AF: You talk about government support as one part of the answer to the downward trajectory of the creative class. But doesn’t that play into the market mentality? Why should institutions with deep pockets — universities, corporations — pay artists when they figure the government will do it?

Timberg: There seems very, very little chance of this being a problem. Even if U.S. arts funding tripled – not bloody likely with a Republicans majority in the House and Senate – it’s hard to imagine every artist and architect and scribe moving smoothly and comfortably onto the federal dole.

Corporations will pay artists because they have to, not out of the goodness of their hearts.

Universities have a better sense of mission – at least, some do — and in some cases a sense of social justice. In an ideal world, they’d be motivated by that, to some extent, as well as by prestige and competitive pressures. But universities are mostly set up to employ administrators and people with Ph. D’s, and to make money for their endowments. Some universities employ writers and artists and allow them to have lively careers there. Some have no idea what they’re doing.

Writer Tobias Wolff — dismissed by some in academe as “a middlebrow craftsman.”

A writer friend in the academy, who I can’t name, told me about hearing Tobias Wolff, the short story master who now teaches at Stanford, dismissed by some academic as a “middlebrow craftsman.” Man, that was when I realized we had a problem.

Another friend, a musician, remembers trying to get academic and financial support to bring the saxophonist Stan Getz to Stanford as an artist-in-residence, and running into all kinds of resistance and dismissals — Getz didn’t have a doctorate and wasn’t a real scholar, and so on. This leaves me speechless.

Some schools, on the other hand, take what are now called “practitioners” seriously. When I was at Wesleyan, I took a class from the jazz composer Anthony Braxton and tried (and failed) to get into a course by the essayist Annie Dillard. Bard College has an incredible lists of artists and writers on its faculty.

But it takes leadership – people who care about arts and culture for their own sake and can summon support for them.

AF: When I tell my artist and arts journalism friends that they must read this book, they inevitably ask “Will it make me depressed?” Richard Florida reached guru status giving the creative class what it wanted – pie-in-the-sky optimism. Why should it read your sobering view?

Timberg: It’s funny – I had to reread the book a few months ago for proofing purposes, and I expected it to be a real downer. This was so long after I’d written most of it that it felt like reading someone else’s work. Whether this book is good or bad I can’t say; I’m too close to it. But I found it at times grimly funny, at times enraging, but never depressing. For the thousands and maybe millions of us who’ve lived through this mess – who’ve seen the consequences close up – it’s not depressing to be told that writers and artists are getting screwed. It’s our daily reality.

What I tried to do in this book was look a problem – or a set of layered problems – square in the eye, without flinching. I asked questions that it took me to places I didn’t expect to go and which will surprise people who know me. I aimed for what the late Nashville songwriter Harlan Howard called “three chords and the truth.” I don’t think telling the truth is depressing. It’s b.s. and hype and pretty little lies and letting the bastards win that’s depressing.

But getting at the roots of a crisis doesn’t depress me. It fills me with energy and hope that someone will hear my call, see things clearly – for a change — and plot a way out. That’s what I’m looking for.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: arts and culture, Culture Clash: The Killing of the Creative Class, middle class

“We’ve lost the very language by which we express the worth of things.”

As a writer and another “middlebrow craftsman,” I’m going to read this book.

Thanks, Bill. The cherry on the top of a terrific week of Arts Fuse.

Haven’t finished reading the entire interview yet but, while I appreciate this author’s starting a discussion about good art and economics, and I am grateful for that, it’s a bit off-putting when he emphasizes the affluent “middle class” whom he believes made “good” choices. First of all, most artists, musicians, writers, etc., don’t own homes and don’t make a lot of money. This has always been true and it mostly has to do with capitalism as we know it here in the US which doesn’t reward giving. (Take a look at Lewis Hyde’s “The Gift.”) Most artists will create regardless of whether or not we earn money from it but without money our work is devalued and possibly won’t last or have a chance to make an impact. That IMHO is the real tragedy.

Timberg’s disregard for the starving artist and emphasis on those who were making money and suddenly aren’t seems elitist and self-serving. What about the blues? Rap? Hip hop? They emerged from poverty, pain and racism, not an affluent middle class.

As I said, thank you for starting the discussion. But it would be nice if you included all talented artists, not just the ones who were lucky enough to earn a living and now suddenly aren’t.

Also the Internet is very democratizing. Anyone can put their music, writing, pictures, whatever up on the ‘net for all to see. The only ppl suffering from that are the big bureaucrats in the music industry. Frankly, the music industry has never been democratic–racist, sexist, classist and elitist. Only a few got signed by the record co’s & usually by selling their souls. Perhaps it’s good then that the “industry” is going down. Might make room for real music, real art in general, to have a chance.