DVD Review: Roman Polanski’s “Macbeth” – A Paranoiac Fever Dream

Among the most haunting aspects of Roman Polanski’s 1971 film version of Macbeth is his visceral depiction of the tragedy’s violence.

Macbeth by William Shakespeare. Directed by Roman Polanski. Released on Blu-Ray and DVD.

The end of Macbeth in Roman Polanski’s film version of Shakespeare’s tragedy.

By Matt Hanson

It’s fitting that The Criterion Collection decided to release its sleek new edition (on Blu-Ray and DVD) of Roman Polanski’s Macbeth in time for Halloween. The director’s 1971 version of ‘the Scottish play’ is a paranoiac fever dream; it is ghoulishly effective and scarily well crafted. Paranoia had been a Polanski specialty since his breakthrough feature Knife in the Water, the unnerving quiet hysteria of Repulsion, and the disturbing mainstream hit Rosemary’s Baby.

The tale of murder, ambition, and witchcraft is the shortest, leanest, and most accessible of Shakespeare’s tragedies, inspiring directors as skilled as Welles and Kurosawa. No less a Shakespeare devotee than Harold Bloom once opined that Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood is the most successful Shakespeare adaptation in film, precisely because of (and not despite) the fact that it doesn’t contain a word of Shakespeare’s original text. Polanski’s version isn’t as radical as that, but it does do justice to the language of the play by emphasizing its cinematic qualities. His version of Shakespeare weaves its dark spell in creative and innovative ways, dramatizing the bloodlust and guilt of Macbeth‘s bedeviled characters (the cast includes Jon Finch, Francesca Annis, Martin Shaw, and Terence Bayler) in a cinema made out of dread and echoes.

Filmed in the bleak, windswept landscapes of England and Wales, Gil Taylor’s cinematography casts an appropriate pall. The Weird Sisters are grotesque crones, complete with gnarled faces and cawing, shrill voices. Polanski’s vision of the story makes powerful use of ominously evocative sound effects; the echoes (of footsteps, voices) generated by the stone labyrinth of Dunsinane Castle are nightmarish. In his famed essay “On the Knocking at the Gate,” Thomas De Quincey couldn’t quite explain how the ominous knocking at the gate scared him so. The film takes a crack at answering him — his sense of “a peculiar awfulness and a depth of solemnity” is given a visceral punch.

The obstacle for any Shakespearean film adaptation lies in how to make the play visually compelling without sacrificing the text. Polanski’s Macbeth succeeds by accepting the challenge: it is unnerving both verbally and visually. Collaborating with the eminent theater critic Kenneth Tynan (who was the film’s dramaturge), the director made the excellent decision to present the soliloquies as voice-overs. According to critic Terrence Rafferty’s informative essay written for the Criterion releases, the inspiration for this choice was Lawrence Olivier’s 1948 Oscar-winning Hamlet, which Polanski saw and admired as a young man.

This Macbeth succeeds where many movie versions of Shakespeare fail. Particularly when translated into film, the plays (especially the tragedies) lose much of their narrative momentum because they sink under the (perceived) literary obligation to deliver chapter and verse. The actors try to master the poetry by articulating every syllable; the result is that they gulp down great staves of verse in a confusing rush. The text isn’t given any room to breathe. The words become muddled and the plot bogs down. Treating the language with conversational brusqueness still holds the mirror up to nature and involves the viewer, which was the Bard’s point in the first place, wasn’t it? Polanski made a wise decision to reject copying the excesses of Elizabethan bombast in favor of an eerie, clipped, and claustrophobic immersion in the text.

Predictably, Polanski interests himself with the slowly unraveling souls of the characters, adding a meditative quality to match the splashy imagery and violence. The latter’s element of savagery is among the most haunting aspects of Polanski’s Macbeth. The film does not shy away from the plot’s grislier aspects. Banquo’s ghost appears at Macbeth’s table with his wounds still fresh, chasing the terrified king around the room and gazing directly into the camera as he bleeds from the neck. The murders in Shakespeare’s play occur offstage; Polanski gives us a ringside seat. Seeing what inspires Macbeth’s subsequent guilt is a nervy way to ratchet up our (and Macbeth’s) perceptions of guilt by spreading more blood around.

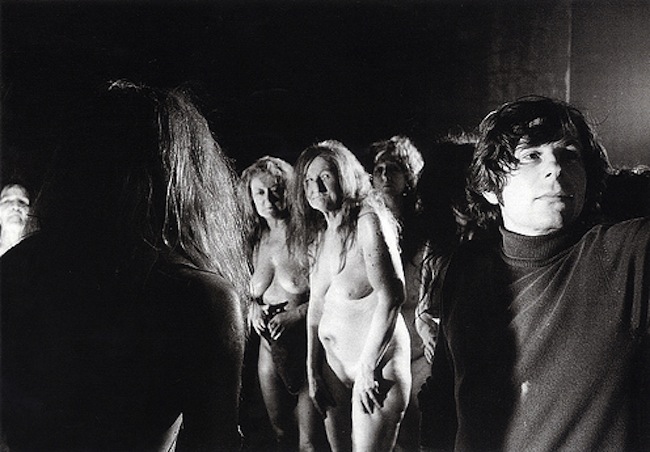

Director Roman Polanski and the actresses playing the “Weird Sisters” in “Macbeth.”

It is relevant that Polanski chose this project not long after’something quite wicked his way came,” the horrific Manson murders. The director decided to make the film roughly a year after the Tate-La Bianca killings, which claimed the lives of several people, including Polanski’s wife Sharon Tate and the couple’s unborn child. There are parallels, strange as it may seem, between the film and the terrible real-life events that preceded it. Rafferty and the cast members who are interviewed on the Criterion edition understandably downplay the resonances, but the connection is significant.

If this connection sounds far-fetched, consider the panning shot where the camera takes in the blood- stained bodies after the assassins (not Macbeth, but under his orders) murder Banquo. Remember that the very person directing the film had once discovered, to his surprise, that such a horrific thing had actually taken place and it had involved his own wife. The intentional fallacy notwithstanding, of all the movies Polanski could have made at that particular point in time, the fact that he chose this material invites the comparison.

Lady Macbeth comes off here as a forceful, Manson-esque sociopath goading her somewhat credulous companion into murder most foul. “Look like the innocent flower but be the serpent underneath it” might have been a Manson Family motto. Macbeth is transformed from a conventional military leader into a cold-blooded killer, “so steeped in blood, as ‘twould be tedious to go o’er.” In Manson’s case, a husband wasn’t manipulated but an ersatz “family” of drugged-up pseudo hippies, until “their very daggers unmannerly breached with gore,” as Macbeth puts it. Is it stretching things too far to see the witch’s cauldron as a magical form of acid? The power of hallucinations bubbling over into madness? And make no mistake about it – Annis’s Lady Macbeth is obsessed with the pleasures of murder for its own sake, not smitten with some scheme to rise, quickly, in the political ranks, no matter what she tells her increasingly agitated husband.

Ultimately, what makes Polanski’s adaptation successful is that like all great directors he doesn’t let the material (no matter how highbrow) intimidate him. There is no pretense to to be ‘definitive.” He knows just what he wants to take from the play. Shakespeare adaptations work best on film when they respect the source material but don’t try to replicate it. Polanski had recently seen the heart of darkness — it should be no surprise that he makes the jaundiced hurlyburly of Macbeth his own.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Macbeth, Matt Hanson, Roman Polanski, The Criterion Collection

What I like most here is the mentioning of Polanski doing it his own way, focusing on the unraveling of the characters and the murders occurring on-screen…rather than attempting to make a film EXACTLY how a Shakespearean play is set up. It makes perfect sense how you correlated the graphic violence with what had recently occurred in his own life a year before. Well done, mate!