Visual Arts Review: M. C. Escher — Shapeshifter Extraordinaire

With over 180 original prints and drawings dating from 1921 to 1969, this retrospective is one of the most extensive and comprehensive exhibitions of M.C. Escher’s work ever presented in New England.

M.C. Escher: Reality and Illusion at the Currier Museum of Art, 150 Ash St, Manchester, NH, through January 5, 2015

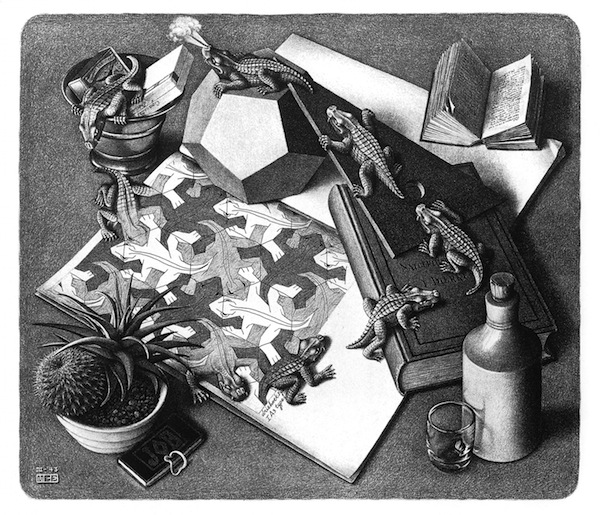

M.C. Escher, “Reptiles,” 1943, lithograph. Photo: The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands.

By Ira Papadopoulou

“Are you sure that a floor cannot also be a ceiling? Are you absolutely certain that you go up when you walk up a staircase? Can you be definite that it is impossible to eat your cake and have it?” – M.C. Escher

The Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972) created a captivating visual world of perfectly articulated impossibilities. Grounded in a playful questioning of our certainties, it’s an eloquently presented vision of the improbable that remains well worth exploring.

With over 180 original prints and drawings dating from 1921 to 1969, this retrospective is one of the most extensive and comprehensive exhibitions of M.C. Escher’s work ever presented in New England. The pieces come from the collection of the Herakleidon Museum in Athens, Greece and are exhibited chronologically across the three gallery spaces. An artist’s interests inevitably shift over the years, but we can also recognize a clear thematic unfolding of his work.

The first gallery features Escher’s earliest and least known creations. The young artist travelled through Europe in the early 20’s, generating a body of work that focused on realistic depictions of landscapes and cityscapes. The Italian countryside and its architecture (Amalfi, Calabria, Sicily, Siena) prevail in this part of the exhibition; the finesse and the precision of detail in Escher’s pen and ink, pencil or woodcut works amaze.

It’s also surprising to find quite a few works with religious content – Saint Vincent Martyr (1925); Second Day of Creation (1925); Saint Francis Preaching to the Birds (1922); Tower of Babel, (1928) – and some rarely-exhibited portraits of Escher’s father and the artist’s wife.

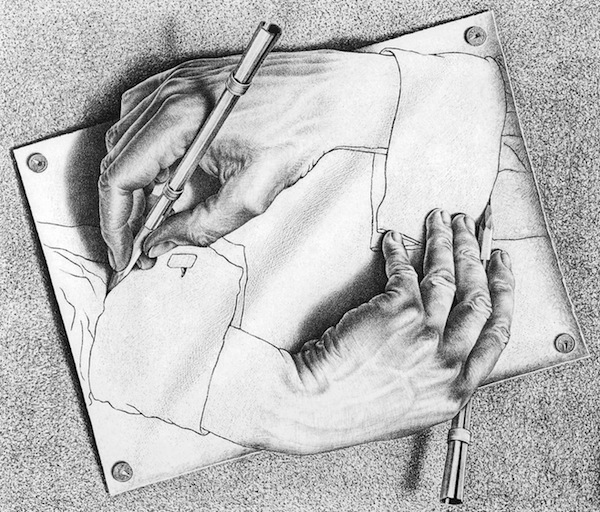

M.C. Escher, “Drawing Hands,” 1948, lithograph. Photo: The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands.

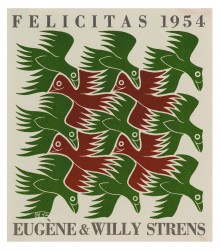

The second gallery reveals Escher’s artistic breadth: book plates, covers, illustrations, and New Year greeting cards as well as large-scale works; explorations of many printing techniques (woodcut, wood engraving, lithography, intaglio), and the use of tessellation and other complicated mathematical structures.

Escher’s exploration of tessellation (geometric patterns with no overlaps and no gaps) was inspired by his 1936 visit to Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. Captivated by the decorative Moorish designs on the floors and walls, he began creating compositions – either of abstract or of recognizable forms- made up of the same infinite, interlocking patterns. From this moment on his fascination with tessellation and geometry became a major imaginative element in his work.

Visitors should not miss iconic works like: Cycle (1938); Drawing Hands (1948); Day and Night (1938); The Sky and Water I (1938). The latter, an amazing interplay of birds & fish / air & water, has been often used by scientists for the study of visual perception.

It’s hard to miss the astonishingly long (13 1/2 feet in length) woodcut Metamorphosis (1939-40), a monumental print created with multiple woodblocks and colors. It is a remarkable work, marked by constant shape-shifting, a piece that could be almost identified as visual poetry. Here Escher unfolds a magical world where words become shapes, shapes become creatures, creatures become cubes, cubes become cities, and cityscapes become chessboard landscapes that resolve back into words. By ending where he began, Escher uses his shifting figures and spaces to play for the sake of play, to revel in the infinite metamorphoses of things. Visually, he grasps the essence of a Heraclitian ever-changing universe, where everything flows.

The third and final gallery, Escher’s “Impossible Worlds,” contains several of his most popular and recognizable works, such as Belvedere (1958) and Relativity (1953). Here his extraordinary fantasy constructions are captivating visual environments whose antic unlikeliness beguile. The laws of gravity do not apply: staircases are endlessly ascending or descending but somehow remain the same height, ceilings are also floors, or windows or balconies. And all this helter-skletering gives off an impression of harmony!

M.C. Escher, “Air,” 1952, woodcut. Photo: The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands.

Escher’s imaginary spatial constructions challenge the visitor to solve what seems to be a “visual enigma.” They are difficult to figure out, but the exhibition’s labels and text panels provide concise and coherent explanations of Escher’s mathematical methods and printmaking techniques.

The exhibition also features original wood blocks and lithographic stones used to print, while throughout the galleries there are interactive learning opportunities for visitors who are interested in a hands-on experience of how tessellations work, or how to create Escher-inspired self-portraits. The magnifying glasses on offer to examine “up-close” Escher’s printmaking techniques are definitely a nice touch.

Leaving the galleries and returning to Currier’s main entrance hall – a bright, two-storey atrium with arches, ionic columns, and beautiful marble staircases – I had a vague feeling that I had become a star in one of Escher’s captivating works. So I stood in the middle of the hall, I looked around me, and I asked myself: Am I sure that the floor cannot also be a ceiling? Am I absolutely certain that I go up when I walk up the staircase?

Ira Papadopoulou is an arts manager and curator. She studied Sociology, Communications and Arts Management in London, UK. For over a decade, she served as Director of Cultural Affairs for the Hellenic-American Union, a cultural and educational institution in Athens, Greece, where she was responsible for the institution’s cultural activities, including planning, curation and the implementation of a wide range of artistic, public and educational programs. She currently resides in Boston.