Music Commentary: “I’ve neither seen nor heard it, but I don’t like it. (And neither should you.)”: “The Death of Klinghoffer” Meets the Know-Nothing Protest

What we seem to have here is one of the glories of our democracy in action: the blind leading the oblivious; aping distortions and downright falsehoods about the opera; and demanding, in their exercise of free speech, that the Met’s same right be curtailed.

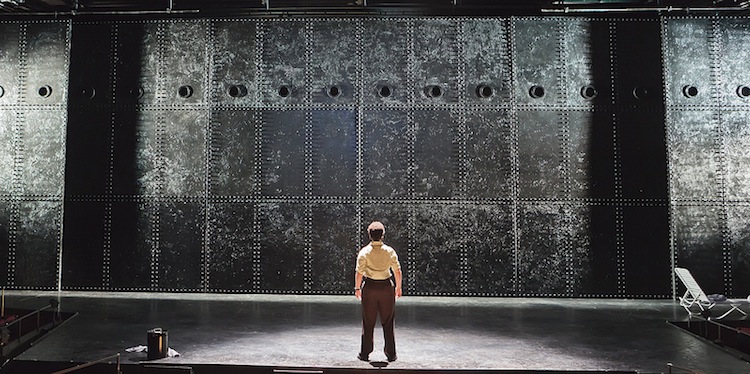

Protesters across the street from the Metropolitan Opera’s production of “The Death of Klinghoffer” at Lincoln Center in New York City. Photo: Peter Foley/EPA/Landov.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

“There is nothing more frightful than ignorance in action.” So wrote Johann Wolfgang von Goethe two hundred some years ago. At the time, he was speaking about bigger things, but his observation might be aptly applied to the parade of protesters lining up to greet the Metropolitan Opera’s current production of John Adams’s opera, The Death of Klinghoffer.

Adams’s 1991 score is no stranger to controversy. Premiered in Belgium as the first Gulf War wound down, it tells the story of the 1985 hijacking of the cruise liner Achille Lauro and the murder of the wheelchair-bound American passenger, Leon Klinghoffer. Adams and his creative team (which included librettist Alice Goodman and director Peter Sellars) opted to turn the story into a meditation on violence in the Middle East, essentially a two-and-a-half-hour-long commentary on the theme of timeless conflict between irreconcilable foes. In so doing, they made what their critics consider a fatal mistake: giving voice to Palestinian terrorists. The opera’s American premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in September 1991 turned into a firestorm. Critical reaction was largely (though not entirely) negative and, most damning, the Klinghoffer’s daughters released a statement in which they described the opera as “seem[ing] to us to be anti-Semitic.”

That last charge stuck. You hear (and can see) it parroted almost daily at Lincoln Center. But are there any grounds for it? In 2001, musicologist Richard Taruskin offered up a typically outspoken verdict on The Death of Klinghoffer, attempting to support the anti-Semitic charge through a selective analysis of the score. But even backed by the might of his powerful intellect, the argument was a tough sell.

The crux of Taruskin’s case had to do with the way Adams portrayed various terrorists, musically, particularly how he illuminated some of their singing with sustained halos of sound, or “aureoles.” In the Bach Passions, this device is used to offset the words of Christ. And, yes, in Klinghoffer, “aureoles” sometimes accompany the lines of the terrorists, but, as Robert Fink has pointed out in his convincing rebuttal of Taruskin’s argument, such gestures accompany the voices of other characters, too, including the Klinghoffers. Is this a case of moral equivalence, just a coincidence, or something else?

It’s the latter, I’d argue (along with Fink). Though the model of Bach’s Passions looms large throughout Klinghoffer (with big choruses serving as dramatic pillars, the original staging unfolding ritualistically, etc.), Adams’s use of “aureoles” is very different from Bach’s. In The Death of Klinghoffer, they offset not the characters themselves but the opera’s important ideas. Thus, you find them in the opening “Chorus of Exiled Palestinians” and accompanying the unsettling arias of terrorists, as well as framing the words of Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer. It’s highly controversial – and charged – political theater, for sure; but it’s also highly effective drama. And, ultimately, drama is what opera’s about.

The drama unfolding outside the Met these days recycles the thrust, if not all the specific details, of Taruskin’s heartfelt but largely disproved essay. Protesters complain about the opera being anti-Semitic and anti-Israel, of glorifying terrorism and murder. They rehash grievances about giving a voice – any voice for any reason, musical, dramatic, or political – to PLO terrorists. And they demand that the Met cancel the whole shebang. None of it’s very original.

What is unique, though, is a fact at least as appalling as the Klinghoffer protesters purport the opera to be: it appears that most of those opposing the Met’s production have neither seen nor heard the work in question. Abraham Foxman, whose lobbying of Met general manager Peter Gelb this summer resulted in the cancellation of the company’s scheduled HD simulcast and radio broadcast, hasn’t. Neither, apparently, have the vast majority of those waving signs and shouting slogans at Lincoln Center who have been interviewed by the New York Times, NPR, and other news outlets. (It’s also hard to imagine George Pataki or Peter King, two other high-profile Klinghoffer-phobes, having sat through the piece either, but there’s no official record one way or another.) Rudy Giuliani, who led Monday night’s protest against the Met’s first performance of the opera, apparently owns a recording of it that he has listened to several times – he has some complimentary words about Adams and, even, Klinghoffer, in a recent Times interview – but he’s joining the protests to give voice to his complaints about the work’s “distorted view of history.”

Alan Opie, playing Leon Klinghoffer (R) and Jesse Kovarksy, playing Omar perform during a dress rehearsal of John Adam’s opera “The Death of Klinghoffer” at the English National Opera in 2012 in London.

At least Giuliani’s actually heard Klinghoffer. In this, his example stands out among his fellow protesters like the blazing sun on a stormy day. Otherwise, what we seem to have here is one of the glories of our democracy in action: the blind leading the oblivious; aping distortions and downright falsehoods about the opera; and demanding, in their exercise of free speech, that the Met’s same right be curtailed. If you like irony, this is heaven; if you value informed discussion or debate, it’s the other place.

*****

This isn’t to say that The Death of Klinghoffer is a perfect opera: far from it. Dramatically, it’s sluggish and unbalanced. Some of its characters are superfluous. Goodman’s libretto can be naïve and reductive. Like most adaptations of historical events, it does play fast and loose with some historical facts (probably the most serious charge you can legitimately aim at the work), and can get mired in its own grandiloquence. And Adams’s score, with its weird mélange of electronic and acoustic sounds can, at times, come across as trite.

But to suggest that, by giving voice to objectionable characters, Adams, Goodman, and Sellars were providing implicit endorsements for their actions is more than a bit presumptuous (not to mention dubious, logically). And such a mindset doesn’t take into account either the power of the music to shape and present those voices in a particular way or does it consider the context in which the grievances of these characters appear. It’s not too much to say that anyone who comes away from The Death of Klinghoffer with the impression that it’s anti-Semitic, espouses terrorism, or glorifies the murder of its title character is missing the forest for the trees.

Much of Adams’s music in it is articulate and powerful. The seven choruses alone are masterpieces of musical poetry. His treatment of both Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer is consistently respectful and moving. In his two relatively short appearances, Leon Klinghoffer comes across as tremendously dignified. And Marilyn Klinghoffer’s wrenching final aria of rage and inconsolable loss is one of the most compelling episodes in opera of any time or place.

You don’t hear anything about that in these protests. Instead, you see signs advertising that “The Met Glorifies Terror,” “Opera Justifies Attacks on America, Israel, Jews,” and “Gelb – Are You Taking Terror $$$,” among others.

There are complaints about the title. The word “death” is thought to trivialize Leon Klinghoffer’s murder, as though the opera somehow tries to covers up the manner of his death (it doesn’t, though in the original production it occurred off-stage; in Tom Morris’s new one, it happens in full view of the audience) or that the tragedy of his murder doesn’t form the opera’s dramatic heart (it does). Never mind, too, that its name places The Death of Klinghoffer in a long, distinguished tradition of dramatic works with similar titles. “It’s part of dramatic history,” Sellars has argued. Such subtleties and historical (or cultural) awareness isn’t appreciated on the picket line.

Neither do the opera’s dissenters care for anything approaching context. On the contrary, one hears a lot of select Klinghoffer lyrics grossly ripped out of it. A terrorist called Rambo sings “America/is one big Jew” and “Wherever poor men/Are gathered they can/Find Jews getting fat.” As you might have guessed, he’s a particularly brutish thug. You’ve seen his type most recently in videos of Al Qaeda and ISIS. The words he sings are of course offensive. Yet they’re true to the character. One wonders what the opera’s detractors think he should be saying instead. Whether or not you find him sympathetic is, ultimately, a matter of personal choice, but it doesn’t seem that Adams or Goodman found (or made) Rambo terribly attractive: the music he sings is as violent and abusive as his words are abhorrent.

The whole concept that the meaning of a text might be transformed by its music is rather lost on the madding crowd, too. Take the second act-aria of the terrorist Omar, a paean to martyrdom and death. By themselves, his words read like an advertisement for jihad: “My soul is/All violence./My heart will break/If I do not walk in Paradise/Within two days” runs a passage towards the end. Troubling lyrics? Absolutely. But, again, pretty much the sentiments you’d expect from an Islamic fundamentalist zealot. When set to music, though, there’s nothing appealing about this character or the scenario he paints; on the contrary, the result is terrifying. Accelerating, pulsing, plucked strings unsettle the texture. Menacing brass chords rise like flames. The melismatic vocal line sounds like Donizetti on a bad acid trip. Rhythmic dissonance is everywhere. To top it off, piccolo and synthesizer engage in a spastic dialogue with the timpani rumbling underneath. If this is music that glorifies terrorism, as the opera’s opponents would have it, I shudder to think what Adams might concoct to damn it.

*****

Perhaps, if they had heard the opera, more of its opponents would realize this. But the more they speak about Klinghoffer’s supposed shortcomings, the clearer it becomes just how little they know the work.

Adam Langer’s summary of a recent meeting of protesters at the Walter Reade Theater describes a handful of reasonable arguments (Charles Asher Small touching on the sense of moral equivalence he feels runs through the opera and Jonathan Tobin filling the Taruskin-ish void, talking about Klinghoffer representing an academic, leftist view of the conflict in the Middle East) but many more bordering on (or crossing the line into) inanity.

Author Phyllis Chesler complains that the “villains have more lines.” She’s right: there’s a better than two-to-one advantage in arias for the “bad guys.” But, in practice, what does that really translate into? Giving background to a less familiar story, in part. Justifying the terrorist’s grievances and excusing their actions? Hardly. Goodman may as well have given the terrorists fifty arias: their cumulative effect doesn’t come close to trumping the simple decency her libretto gives either of the Klinghoffers in theirs.

A scene from the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis production of “The Death of Klinghoffer.” Photo: Ken Howard/Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

Dahn Hiuni argues that the terrorists essentially cast a spell with their singing. His spurious logic? “People like people who sing. We are sympathetic to people who sing.” If only it were that simple. Simon Deng (who hasn’t seen it but considers Klinghoffer to be “sheer rubbish”) asks, bizarrely, “How do you make fun of an innocent person being murdered,” as if that’s the point of the opera. The event concludes on a menacing note with the vitriolic agitator Jeffrey Wiesenfeld declaring that he wants to make sure “no opera house will ever show this opera again.”

The meeting appears, like most of these protests, to be a mix of heartfelt opposition and virulent anger directed towards a perception of the opera rather than the reality of it. It’s the sort of response you don’t expect from New Yorkers who pride themselves in their intellect, cultural awareness, and open-mindedness; then again, New York’s a big city.

That last fact was on full display Monday night, when Giuliani and a number of other public figures from both sides of the aisle attempted to take further whacks at the piece. Melinda Katz, borough president of Queens, told how she was “personally offended by the play.” Former governor David Paterson called in “loathsome and despicable.” Wiesenfeld ranted. Giuliani offered that the opera “supports terror.” Perhaps the most remarkable commentary on Klinghoffer, though, came courtesy of a pamphlet from the Zionist Organization of America, which decried it as “anti-Semitic, pro-terrorist, anti-American, anti-British, anti-gay, & anti-western world.”

For its part, the Met hasn’t really helped matters. First, it kowtowed to outside pressure and cancelled the broadcasts scheduled for November. Then, last month, it quietly shelved plans to hold public discussions with the production’s creative team after several participants withdrew. According to the New York Times, the official reason for the withdrawals was scheduling conflicts, though there have been security concerns, as well.

Still, if any recent composition might benefit from extended efforts of public discourse and education, this is probably the one. The fact that the measured replies of Gelb, Adams, and the rest of the production’s creative team have been sometimes drowned out by the loud chorus of ill-informed, cloddish protesters is arguably a partial result of the timid PR approach the Met has taken to the piece. But, then, it’s perhaps naïve to think that any amount of reasoning or dialogue would sway the likes of the vituperative Wiesenfeld, who’s also called for the Met’s Klinghoffer set to be burned to the ground.

*****

Last year, in a paper I delivered at Yale, I discussed one of the chief complaints – many years old at this point and, surprisingly, not cropping up as loudly as others in these protests – about Adams’s approach to drama, namely his unwillingness to “sermonize” on good and bad or right and wrong in his dramatic works. This is a choice that’s at the crux of his artistic worldview and very apparent in The Death of Klinghoffer. Adams, I said then, “isn’t seeking to score points, rather, he…trusts his audience to…respond [to the work] as they see fit.”

It’s a very postmodern approach and not without its risks. For one, it assumes a level of education and intellectual engagement from the audience in the work at hand that isn’t always apparent in our society, generally, let alone in the concert hall. Worse, it goes against the grain of how the arts tend to be viewed in this country, particularly music and especially so-called “classical music.” To too many, the latter is not much more than a kind of benign aural curative. When it doesn’t fulfill that role, when it provokes (as Klinghoffer does) what’s to be made of or done with it?

It’s significant to note, though, that, in Klinghoffer, Adams’s method of not emphasizing clear-cut answers and Goodman’s willingness to let all sides speak out isn’t new. Shakespeare did it. So did Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, and Puccini, among countless others. More than half a century ago, Leonard Bernstein – himself no stranger to controversy – observed that the purpose of serious works of art isn’t palliative, rather “a work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” If any modern opera lives up to that lofty statement, surely it is Adams’s, Goodman’s, and Sellars’s complex and imperfect, but deeply moving, The Death of Klinghoffer.

If, in Klinghoffer, Adams doesn’t justify or glorify the actions of the terrorists, neither does he beat you over the head with an explicit condemnation of their behavior. But what he does do by the way of his artistry is to provide some sense of moral clarity, an ethical vision that is subtle and powerful, both dramatically and psychologically.

As I noted above, Adams and Goodman gave the last word in the opera to the devastated character of Marilyn Klinghoffer. Her haunting, prophetic words are both noble and wrenching, lamenting her husband’s unjust death and remembering him (“We used to sit at home/Together at night/When the children were out/I wouldn’t glance up/From the book on my lap/For hours at a time,/And yet it was the same/As if I had gazed at him/I knew his face so well”), and anticipating the continued cycle of violence (“If a hundred/People were murdered/And their blood/Flowed in the wake/Of this ship like/Oil, only then/Would the world intervene”). Throughout comes the refrain of a woman dying of cancer (the real Marilyn Klinghoffer passed away of the disease four months after the hijacking): “They should have killed me./I wanted to die.”

Here you have the Shakespearean tragedy at the heart of The Death of Klinghoffer summed up in a nutshell, simultaneously global and deeply personal. To hear this aria in the context of all that’s come before is to experience one of the most shattering, metamorphic scenes in all opera. It is poignant and unforgettable. Los Angeles Times music critic Mark Swed described the aria as hearing Marilyn’s “sorrow against a larger context. Her tears are reminiscent of those of Mary in the Passions, and Klinghoffer’s death comes to seem almost Christ-like, suggesting that there is a greater good to be gained from all this.”

What good? Well, that remains to be seen – the cycle of senseless violence of course continues to this day. But there is no question, by the time you get to the end, that the opera views the murder of Leon Klinghoffer as a despicable, irredeemable act of cowardly violence. Its most human characters, its most sympathetic ones, are not the perpetrators of that violence; rather, they’re the victims at the heart of its narrative. You don’t need an advanced degree to understand this, just the ability to sit through The Death of Klinghoffer to the end.

*****

Protesting is, of course, a First Amendment right. And I fully appreciate that The Death of Klinghoffer touches on, in a sometimes-provocative way, some very difficult political, cultural, and religious subject matter. It’s a hard piece that relates a terrible story. And its creative team isn’t guiltless when it comes to offering some historically tenuous and intellectually shallow explanations of Mideast violence, both in Klinghoffer and to the press. But, if these protests have reinforced anything, it’s the necessity that those opposed to something need some first-hand experience with the actual subject of their opposition before they start raising their voices or waving their signs. Hearsay, half-truths, and worse are dangerous substitutes for facts and no foundation whatsoever for anything more than a screed.

So, to those protesting in Lincoln Center who haven’t yet seen Klinghoffer, here’s my advice: calm down, buy a ticket, and attend a performance. If, after you get to the end of it and have spent a day or two thinking about what you saw, you still think it’s content objectionable, by all means go pick up your placard (or, better, make a new one) and stand outside again. Let no one stop you. Until then, keep your ignorance about the opera to yourself.

The willful indifference of too many to the actual content of The Death of Klinghoffer does neither them nor their arguments any favors. At the least, it’s an embarrassing demonstration of a low level of cultural engagement and education; at worst, it’s the spewing of nescient bile. The former is regrettable but easily remediable while the latter quickly leads to some pretty nasty places. We shouldn’t – and needn’t – go down either road.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: John Adams, Metropolitan Opera, Peter Gelb, Richard Taruskin, Robert Fink

Welcome to the “beauty” of America – freedom of speech combined with little knowledge and the power of crowds! In my mind this equals free advertising (another capitalist value!)