Book Review: Sanford Friedman’s Utterly Original “Conversations with Beethoven”

How well Conversations with Beethoven works as fiction will depend on the engagement and imaginative powers of the reader. I for one have never read or heard of a book all at once so compelling and puzzling.

Conversations with Beethoven

By Sanford Friedman, introduction by Richard Howard. New York Review Books. Paper. 285 pp. $16.95.

Totempole

By Sanford Friedman, afterword by Peter Cameron. New York Review Books. Paper. 419 pp. $16.95.

By David Mehegan

The remarkable New York Review of Books series continues with the heretofore unpublished last novel of Sanford Friedman, Conversations with Beethoven, along with a reissue of his 1965 novel, Totempole, originally published by E.P. Dutton.

Conversations with Beethoven, written in the 1980s, was inspired by a historical curiosity. In the latter years of Ludwig van Beethoven’s life, when he was completely deaf, his friends, relatives, and associates communicated with him by means of hastily written notes. He could and did respond with speech. The result was a large body of on-the-spot epistles of a kind, but all on one side. It was Friedman’s inspired, inventive idea to search these surviving notes and fashion them into a sort of novel of Beethoven’s tormented last year. The result is thoroughly fascinating, often amusing, touching, and pathetic, but how well it works as fiction will depend on the engagement and imaginative powers of the reader. I for one have never read or heard of a book all at once so compelling and puzzling. It is utterly original.

Following a brief epigraph from the nineteenth-century composer Ferdinand Hiller, explaining the “thick booklets” of paper and pencils which Beethoven kept nearby for others to use, the book begins with a “Speakers” page, a list of twenty-one persons, each of whom addresses the composer with a different term of address. Those of the family are as expected. Nephew Karl, who caused him no end of torment, calls him “Uncle”; his brother Johann calls him “Brother”; two sisters-in-law call him “Ludwig” and “Brother-in Law”; a close friend also calls him “Ludwig.” Surrounding this inner circle is a congeries of observers and camp followers, including a banker, a biographer, a composer, a boy servant, an appalling assortment (five) of useless doctors, and others, each using a distinctive mode of address: Maestro Beethoven, Revered Maestro, Great Maestro, Esteemed Patient, Celebrated Patient, Honored Guest, Dear Friend, Venerated Composer, etc.

Apart from a few letters from Beethoven and a short sequence of his words printed in italic, the text consists primarily of speech derived from the notebooks. It is not claimed, so far as I can see, that any of the speeches in the novel are transcripts of the historical notes; they appear to be freely adapted or invented by the author. Each sequence of “dialogue” – if one can call it that — begins with one of the titles of address. Since the book has no narrator, they are the equivalent of speaker-names in a dramatic script, letting us know who has the floor.

Because the interlocutors are writing and the composer is speaking, we of course must guess at his side of the conversations, based upon the others’ sometimes angry, frustrated, or surprised responses. For example, this exchange in a quarrel between Beethoven and nephew Karl, in which the youth is accused of sleeping with his aunt Therese, wife of Johann:

I’ve sworn on my honor that I take no interest in her – What more would you have me say?

Naturally I heard you, doubtless you were heard in Krems.

On the contrary my silence signifies disdain – it’s beneath me to refute such accusations.

Why, when you already have my word?

Well and good, I give my word that I am not fornicating with Fat Stuff [Karl’s name for his aunt].

There! Are you now satisfied?

I am not lying!

Then let us drop the subject.

Kindly refrain from saying that.

It’s pointless to make a scene.

You have only to drop the subject in order to

Please, I beg of you to drop

But I have told you the truth!

I have – I have!!!

This goes on for several pages. Most of the dialogue in the book consists of longer blocks of speech than these, but the puzzle for the reader is unrelenting, and not fully solvable; that is, you can never be sure of what exactly the great man has said.

Because many of the modes of address are so similar, it is easy to forget who is speaking – which doctor calls him “Celebrated Patient” and which “Esteemed Patient”? The reading is a bit troublesome unless one memorizes the twenty-one titles. (I placed a bookmark on the “Speakers” page so that I could quickly look back to figure out which doctor or sister-in-law or other is speaking.)

The action begins in July 1826 with nephew Karl’s attempted suicide by pistol – a desperate protest against the pressures from his late father’s famous brother, who is his legal guardian. In his “suicide” note before shooting himself in the head, he bitterly complains of Beethoven’s merciless hectoring of him over his irresponsibility and love of pleasure. “I am called a good-for-nothing, a liar, a swindler, a thief! Such accusations are distressing enough when spoken; they are unsupportable when shouted at the top of one’s lungs in a towering rage, as is your habit.” The youth recovers from his wound, giving new meaning to the word “headstrong,” but continues to be a headache to his uncle for the brief remainder of his life.

The story ends with Beethoven’s death eight months later, March 26, 1827. He is afflicted with dropsy, that is, edema, severe retention of fluid in his abdomen. At the time this was considered a disease unto itself, whereas now it is known to be a symptom with several possible causes, such as congestive heart failure. Apparently he drank like a fish; the autopsy revealed severe cirrhosis of the liver.

In the final months of his life, he is trying desperately to finish the tenth symphony, though we do not see any of his creative endeavors, his writing or working at the piano. Mostly he is consumed with details, such as getting a portion of a score to the printer. As much as with his music, he is obsessed with Karl, whom he both harasses and indulges. The youth apparently loves gambling and wenching, though of course we do not see it. Beethoven’s brother Johann insists that the only cure for Karl’s irresponsibility is to get him into the Austrian army as a junior officer. The composer is appalled at this fate for the dear boy, whom he thinks of as his son (although the feeling is not requited), but agrees reluctantly, and much of the action concerns the effort to persuade the military authorities that the mysterious scar on the kid’s skull need not be explained before he can receive a commission. Beethoven loathes the boy’s mother, Joanna, whom he accuses (with no evidence) of having poisoned her husband, his brother, years before and much of the drama over Karl consists of the struggle to prevent him from having anything to do with her. This Karl resists, since naturally enough he is attached to his mother.

While this is going on, Beethoven’s condition worsens, and various doctors are called in, none of whom can do a thing for him. They are greedy, incompetent, vain, clownish, and subject him to a horrifying sequence of painful operations to drain fluid, all of which does him no good and makes him steadily weaker. Dr. Andreas Wawruch visits the patient after one of the operations:

Esteemed patient, not only am I surprised but extremely pleased and, I may say, proud to find you up and about again. Success in the medical art, like success composing, is never unwelcome. As you doubtless know, it was Hippocrates who coined the phrase, albeit in Greek, to be sure, ars longa, vita brevis. [Life is short, the art is long]

If you were dying, I would have to agree with you that the remark is in poor taste. Since, however, you are so much better today I can only conclude that an exception has been made in Beethoven’s case: et ars et vita longae. [art and life are long]

As death approaches, Beethoven becomes obsessed with contriving a way to leave his estate to Karl in such a way that Joanna cannot get her hands on it. In a sense, however, she has the last word, in that the novel ends with her long letter to Karl, as it began with one from Karl, a catty report on the great man’s funeral in which virtually all the participants are described with a sneer.

Sanford Friedman — there is, to be sure, something decidedly odd about a novel about Ludwig van Beethoven that has almost nothing in it about music.

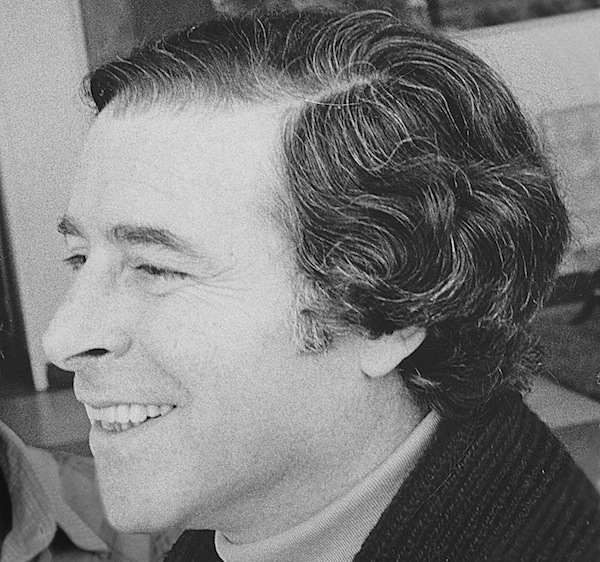

Sanford Friedman, author of four other novels, was a decorated Korean War veteran, playwright, and dramaturge. In later years (he died in 2010) he taught writing at the Julliard School and in a program called SAGE, Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders. His gift for speech is impressively on display in Conversations with Beethoven — in form it seems indeed more like a script than a novel.

It is not clear, even from the extremely short and not especially illuminating introduction by poet Richard Howard, why no publisher would accept the book. (Howard does manage to tell us twice over these seven paragraphs that he had lived with Friedman for nineteen years, and that he “lived against him [italic in original] in the years after.” Does this mean he was an enemy? and if so why would he have been asked to write this introduction?) One can easily imagine any number of editors reading the manuscript and saying, “Feels like a play, but not much of a novel.”

There is, to be sure, something decidedly odd about a novel about Ludwig van Beethoven that has almost nothing in it about music. What we see is a romantic, almost baroque figure of passion, paranoia, and contortion, enduring sufferings (apart from his illness) and quarrels with others that are largely of his own making. Tragic and unnecessary as these struggles seem to be, however, one suspects that had he not been such a person, he could not have achieved the enormous creative output of his life. But all of that output is offstage and unheard. The story is about everything else that is going on in a great man’s life.

Of course, Conversations with Beethoven could not be a play as is. Were it to be, the composer would have to be cast, would have to speak, and would dominate the stage (presumably the chief prop would be a piano). In the novel, Beethoven is weirdly diaphanous, a sort of ghost who is not seen nor heard, but is nevertheless always at the center of the action.

Odd, as I said, as the absence of music at first seems, a subtext is implicit. Wawruch is correct that “ars longa, vita brevis.” In the conceit of this novel there is a subtle parallel with the nature of music itself, and our relationship with a composer. When we hear Beethoven’s music in a concert hall, we have a sense of his presence even though we do not see him. The evidence of that presence is more real to us than the sick, tired, and neurotic figure of flesh and bone who thought of and penned the notes of dozens of beloved works, whom we cannot see or meet. In an interview in the liner notes with his 1991 recording of the six Bach suites for unaccompanied cello (EMI Classic, 1995), Mstislav Rostropovich said, “I cannot imagine that Beethoven, Mozart and Bach are dead. It doesn’t seem so to me. I believe they are alive, but exist in a different condition as if they’re not ‘at home.’” Offstage, that is, as the epic genius is in Conversations with Beethoven, even though he is the only one of interest, the only one who matters.

If Conversations with Beethoven is like nothing you’ve read before, Totempole is more conventional, in structure and style if not in content. It concerns a Jewish boy born in 1928, much like Friedman himself, who gradually understands and accepts his homosexuality. Stephen Wolfe, the protagonist, is a child in New York City as the novel opens, grows up in the Depression with a depressed mother and domineering father, joins the army and serves in the Korean War, where an intense relationship with a Korean doctor opens him to the identity which he has long denied and struggled against. The narrative is fairly explicit in physical terms, though much more so in the realm of the heart, in which sense it is about that which makes gay sex and love like any other kind, in which the individual must decide, “Do I have a right to have this, and if so how?”

Totempole was never hidden or secret, never banned in Boston.The Dutton hardcover was followed by a mass-market Signet paperback that went through several printings, and in 1984 the book was republished by North Point Press, an imprint of Farrar Straus & Giroux. It was widely reviewed. Still somehow it flew under the fame radar. Novelist Peter Cameron begins his afterword by asking, “How could it be that I never heard of Sanford Friedman’s amazing novel Totempole? … that I, a gay man of a certain age, who spent the first half my life covertly reading any novel that was rumored to have something – anything – to do with homosexuality … how is it possible that until very recently Totempole had entirely escaped my attention?”

Perhaps it was viewed as a specialized book with a limited audience, like a western or a book about dogs – a book for “those people.” It probably would not have been Hollywood material, nor can one imagine a high-profile book tour or series of appearances on television or radio. A lot of people would have wanted to screw up their faces and look away. In the New York Times Book Review, reviewer Webster Schott wrote, “The explicit homosexual novel can now be published in the United States. What has freedom wrought?” The book itself he dismisses as “a maudlin hash…a pretty good report on genteel deviant behavior.”

Cameron’s afterword is thorough and perceptive. Possibly he is better equipped to assess and analyze the book than one who had “lived against” the author. Totempole is intense and richly readable, and to me its portrayal of middle-class Jewish life in the Depression, and of a family fairly exploding with internal tension, is no less compelling than the sexual theme. It is all about fear and longing, the impulse to draw apart, and the contrary need to “only connect” and survive as a realized human being.

David Mehegan is a contributing writer. He can be reached at dmehegan@gmail.bu.edu.

Tagged: Conversations with Beethoven, Music, New York Review Books, Peter Cameron, Richard Howard, Sanford Friedman, gay fiction