Book Interview: Jim Vrabel Explores Boston’s History from the Grassroots Perspective

A People’s History of the New Boston takes the “grassroots” view and tries to give overdue credit to the role that community activists and neighborhood residents played in building the “New Boston.”

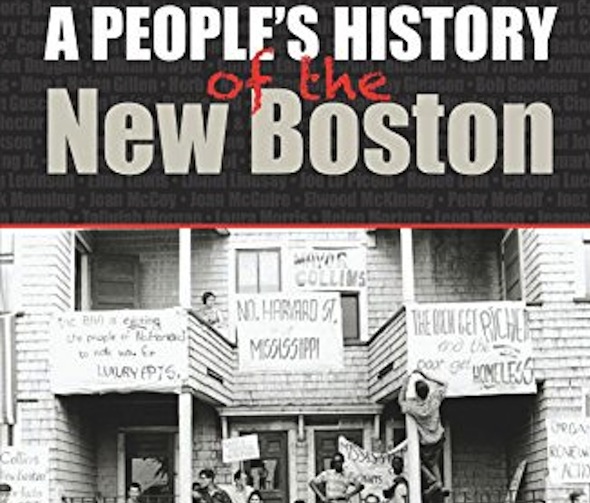

A People’s History of the New Boston, by Jim Vrabel. University of Massachusetts Press, 282 pages, $24.95.

By Blake Maddux

Longtime Boston resident, activist, and historian Jim Vrabel is somewhat tight-lipped when it comes to his personal biography. Suffice it to say, as he wrote in an e-mail to me, he “came to Boston to attend college in 1966, settled soon after on Mission Hill and subsequently became active in the neighborhood.”

An Internet search reveals a few more morsels, such as that he co-authored a piece for The Nation in 2008, co-wrote John Paul II: A Personal Portrait of the Pope and the Man with former Boston mayor and Ambassador to the Vatican Raymond Flynn, and that he is “a former newspaper reporter and speechwriter.”

Finally, the “about the author” page of his latest book A People’s History of the New Boston lists the several local activist groups that he either founded or participated in at the upper echelons. It also mentions that he is the author of When in Boston: A Time Line & Almanac and Homage to Henry: A Dramatization of John Berryman’s “The Dream Songs.”

So while Mr. Vrabel may prefer to keep the details of his private life private, he has plenty to say about the city in which he has spent nearly five decades and watched transform, literally and figuratively, before his very eyes. While his new book could have been a memoir, it is not written in the first person, and Vrabel never puts himself at the center of the action.

Vrabel will be discussing A People’s History of the New Boston at Porter Square Books on Wednesday, October 1 at 7 p.m. He recently agreed to answer some questions via e-mail in advance of this event.

The Arts Fuse: What gap in the written history of Boston does this book fill?

Jim Vrabel: Very little has been written about Boston from the 1950s on, and what has been written often focuses on “top-down” or the “great man” view of that period. A People’s History of the New Boston takes the “grassroots” view and tries to give overdue credit to the role that community activists and neighborhood residents played in building the “New Boston.”

AF: What do you see as time period of the “Old Boston”?

Vrabel: The “Old Boston” – the last era before this one – refers to the period from the beginning of the twentieth century when the people who “owned” the city (the Yankee business elite) withdrew from participation in the city when a new group (Irish-Americans) began to “run” it, and when the manufacturing-based economy faltered to such a degree that Boston was called a “hopeless backwater” and “has-been city.”

AF: You write that “the birth date of the New Boston is usually celebrated as Election Day, November 8, 1949.” However, you also quote Mayor John Hynes as proclaiming that the “beginning of the New Boston” took place on September 1957. What is the significance of each date?

Vrabel: The former date was the day that John B. Hynes defeated James Michael Curley to be elected mayor and began to usher in a less divisive approach to running the city. The latter date is the day that demolition was completed of the New York Streets area, which marked the beginning of urban renewal to Boston, and which sparked the wave of community activism in the city that followed.

AF: How did Boston compare to other cities in terms of change by citizen activism in the second half of the 20th century?

Vrabel: Other cities, particularly those in the Northeast, experienced a similar increase in citizen activism. But I think it may have been more widespread, intense, and effective in Boston because of the city’s small size, its close-knit neighborhoods, and the presence of so many colleges and universities and “mainstream” and “alternative” media outlets.

Author Jim Vrabel — Since coming to Boston in 1966, he has witnessed or taken part in all of the original campaigns described in his book, or their aftermaths.

AF: Which problems remained once New Boston was in place and which new ones were created?

Vrabel: The inability to substantially improve the Boston public schools remains a problem. The growing gap between the rich and poor and the loss of the working class and lower middle class were created – or at least accelerated – since then. The problem of drugs, gangs, and guns – particularly in communities of color – is one that has developed in Boston and in cities across the country in the meantime.

AF: What might the inhabitants of the Old Boston have rued the passing of?

Vrabel: They would have regretted the demise of the many close-knit neighborhoods, in which families could continue to afford to live in for generations, and also of a city that generated substantial numbers of jobs that paid living wages and held promising futures even to those who might not have gone to college.

AF: At one point you write that “if buildings make a neighborhood, it can be said that the South End was preserved. But if people make a neighborhood, an argument can be made that it was replaced.” What do you think was the case?

Vrabel: Both. Although many of the buildings in the South End have been preserved and many of the residents back then no longer remain, as Mel King says in the book, “There’s no question that without organizing, all the number of folks with low incomes would not be here today. No question.”

AF: In 1967, Louise Day Hicks became the first woman to run for mayor of Boston. The first African-American, Mel King, ran in 1979. How many women and African-Americans have been candidates since those years?

Vrabel: Mel King was a finalist in 1983, Peggy-Davis-Mullen in 2001, and Maura Hennigan in 2005. Candidates of color and women candidates in the preliminary elections since then include Eloise Linger in 1983, Bruce Bolling, Rosaria Salerno, and Diane Moriarty in 1993, Sam Yoon in 2009, and Felix Arroyo Jr., John Barros, Charles Clemons Jr., Charlotte Golar Richie, and Charles Yancey in 2013.

AF: With 40 years of hindsight, can you confidently say that busing was a terrible mistake that left more harm than good in its wake?

Vrabel: The desegregation order brought increased equity in terms of resources allocated to all schools, increased hiring of minority administrators and teachers, and improved maintenance to school buildings. But the busing remedy failed to improve the quality of education or promote desegregation. It also drove thousands of children from the system, many of their families from the city, decreased parental involvement in schools, and the loss of the most important community-building institution – the neighborhood school – from Boston.

AF: How many of the episodes that you describe in the book did you personally witness or take part in?

Vrabel: Since coming to Boston in 1966, I’ve witnessed or taken part in all of the original campaigns described in A People’s History of the New Boston, or their aftermaths. As Jovita Fontanez says in the book, “It was an exciting time. There were all kinds of things brewing. It was hard not to be involved.”

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to DigBoston and The Somerville Times. He recently received a master’s degree from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Thesis Prize in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts. He will be teaching a class during the spring term on the First Amendment in American History at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education in Cambridge, MA.

Tagged: A People’s History of the New Boston, Blake Maddux, Boston History, Jim Vrabel, New England History, University of Massachusetts Press