Film Review: Scarlet Roots — Jean Renoir Inspires a Fritz Lang Film Noir

The stupendous Fritz Lang retrospective running over the course of this summer at Harvard Film Archive will soon screen two Lang remakes (in America) of films directed by Jean Renoir.

By Betsy Sherman

They were part of the legion of European filmmakers who fled the Nazis and were snapped up by the Hollywood studios. In their elder years, after having returned to make their final films in their homelands, they were neighbors in Beverly Hills, where both died during the 1970s. Yet as filmmakers, they were a study in contrasts.

The Vienna-born Fritz Lang, schooled in architecture, created worlds in which good struggled with evil against backdrops full of angles that poked at, but never through, the all-powerful geometry of the film frame. Lang used his art to warn audiences about the power-seekers in their midst. On-screen, his characters lived under dark clouds; off-screen, his collaborators would label him a tyrant. On the other hand, the Paris-born Renoir—son of Impressionist painter Pierre Auguste—made warmer, more sensual pictures, the borders of which were more porous, allowing for an often playful sense of irony. Renoir depicted dark clouds as well, but he was buoyed by a belief in a natural order, and a conviction that it’s the artist’s mission to reunite an estranged humanity with nature. Behind the camera—well, Renoir trusted his actors, and they loved him for it.

So it’s curious that the filmographies of Lang and Renoir met in two places. Among Lang’s American films are remakes of two Renoir movies from the 1930s. The stupendous Lang retrospective running over the course of this summer at Harvard Film Archive (through September 1) will soon screen those remakes: the 1945 Scarlet Street (playing Friday, August 1 at 9 p.m.) and the 1954 Human Desire (playing Monday, August 18 at 7 p.m.). The former tells the same story as Renoir’s 1931 La Chienne, each being based on the novel by Georges de la Fouchardière (and a subsequent stage adaptation). The latter follows Renoir’s 1938 La Bête humaine, based on Emile Zola’s novel.

Whereas Lang’s adaptation of the Zola strays so far from the intensity of the novel, and of Renoir’s film, that it becomes almost a case of apples and oranges—the original goes places that the American film industry, under the Production Code, would never go—the transformation of La Chienne into Scarlet Street makes for an appealing examination.

La Chienne (which translates as The Bitch) serves up a stew of prostitution, adultery, sado-masochism, theft, fraud and murder. In Lang’s hands, the story becomes an early example of doom-laden film noir (the director’s German and pre-war American films were, of course, influential predecessors to this post-World War II genre). For Renoir, few of whose films could be called thrillers, it presented the opportunity to depict a seedy urban milieu and to show how a very unlikely fellow’s passage through that milieu utterly changes his life.

Here’s the plot (spoilers ahead): One night on a city sidewalk, a meek cashier and amateur artist (named Maurice Legrand in La Chienne, Christopher Cross in Scarlet Street) who’s married to a monstrous shrew comes to the aid of a young woman (Lulu/Kitty) being beaten by a dapper hoodlum type (Dédé/Johnny). Infatuated, he courts the woman, who in turn is crazy about the hood. Since this coincides with the cashier’s wife threatening to throw out his paintings, he takes an apartment for his new beloved so he can visit her there and have a place to paint. Behind his back, the dame and her guy not only carry on their relationship, but sell the older man’s paintings, claiming that the woman has painted them (she’s discovered as a great new talent!). The cashier, who has been stealing money from his firm in order to support the woman, is shocked when he finds out the hoodlum is her lover. She laughs at him, and he kills her. He then stands by as the boyfriend is charged with murder and executed.

It must be pointed out that Lang’s freedom of expression in Hollywood was much more restricted than that of Renoir, who was able to explore the story’s sexual themes and to frankly show a whore-pimp relationship. In Scarlet Street, in spite of the “scarlet woman” connotation and some mildly suggestive imagery (she, gasp, wears a see-through raincoat), Kitty is never said to be a prostitute (she’s a loafer who makes Chris believe she’s an actress), nor is Johnny shown to be more than a petty hustler.

Renoir was inspired to adapt La Chienne, which would be his second sound film, by the idea of casting Michel Simon as the bourgeois ensnared by the demi-monde duo. Simon, with his distinctive slab of a face, matched by a speech impediment that made it sound like his mouth was full of cotton, could infuse even the most exaggeratedly comedic role with pathos; conversely, he could temper melodrama with sly humor. As Lulu, he cast Janie Marèze, and as Dédé, Georges Flamant. (Renoir recounts in his autobiography how life imitated art, with a tragic end. Simon fell head over heels for Marèze, and she for Flamant. Soon after La Chienne wrapped, Marèze was the passenger in boyfriend Flamant’s flashy new car when he crashed it. She was killed, he survived.)

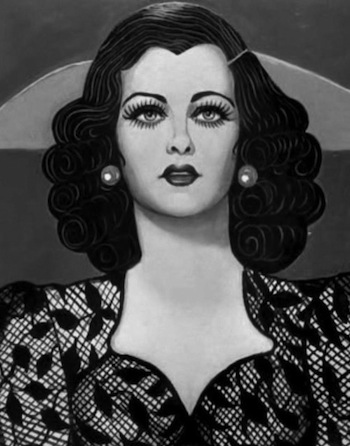

Lang made Scarlet Street as the follow-up to another proto-noir, The Woman in the Window. He heard that Paramount had bought the rights to La Chienne for Ernst Lubitsch; when that project didn’t pan out, he and scenarist Dudley Nichols (who had written for both Lang and Renoir) acquired it. The three Window stars, Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea, would star in Scarlet, and it would be made by the new semi-independent Diana Productions, founded by Bennett, her producer husband Walter Wanger, and Lang. With this film, in which he repeatedly dons an apron, Robinson would put more distance between himself and his previous tough-guy image.

Renoir whimsically, and audaciously, opens the film with Punch-and-Judy type puppets who argue over whether this will be a serious or a comedic story. A third puppet butts in to say it will be neither, and that there will be no moral. Lang and Nichols, however, intend a cautionary tale, and waste no time in setting their Chris Cross up for a tumble (his name seems to signal that he’ll be a martyr). Scarlet Street starts with Chris being given a testimonial dinner by his boss. His colleagues like him, and he has a friend whom he invites over for a Sunday painting session (his wife cedes one territory for his easel—the bathroom). Thus “normalized,” his fall will be harder than that of Renoir’s Maurice, who is belittled by his co-workers and has no friends. Maurice paints next to a window, where he can see happier lives being lived across the courtyard.

Scarlet has what seems like twice the amount of dialogue as La Chienne (for one thing, Kitty has the gift of gab, whereas Lulu is a barely verbal near-idiot), but in Renoir’s film the physical contact between characters has an eloquence of its own.

It’s predictable that these two filmmakers would end their stories differently, and it’s fascinating how they do so. Chris Cross, having killed the woman of his dreams, been fired from his job, and allowed Johnny to have been sent to the electric chair, becomes a Skid Row derelict, forever plagued by echoes of Kitty purring to her Johnny and of the distorted tune “Melancholy Baby” repeating where Kitty’s vinyl platter repeated. Here, shadowy German expressionism meets Catholic inner torment (Lang convinced the morality watchdogs that Chris undergoes a worse punishment than if he had been executed). In Renoir’s epilogue Maurice, too, has become a tramp, but a contended one, one who prefigures the director’s next great role for Simon, the anarchic title character in Boudu Saved from Drowning. There’s a final irony in that he earns a coin in front of the art gallery at which his self-portrait has just been sold for a fortune. All in all, the takeaway is that now he’s free, free from the horrible wife, the boring job, and the two-faced mistress. The curtain that opened on the puppet show now closes.

But wait a sec. Even though Renoir’s film is the more concentrated, more visceral presentation of the cashier’s story, one has to give Lang and Nichols credit for figuring out a brilliant way to put some of the perversity inherent in the sexual story (which they wouldn’t be allowed to film anyway) into the nominal subplot about Chris’s paintings. The paintings in the Renoir film are competent post-Impressionist canvases. Lang devoted more effort to the matter of Chris’s style: he injected a fantastical, Henri Rousseau quality into the artwork.

In La Chienne, Maurice sees his paintings, attributed to a female artist, at a gallery. Lulu makes up a convoluted explanation, and he’s so giddy in her presence he just accepts the situation. But in Scarlet Street, not only does Chris accept the fraud, he eagerly becomes complicit in it. He declares he wants to paint Kitty, and adds “Know what we’re gonna call this? Self-Portrait.” That’s right, he now considers painting her to be painting himself. Lang and Edward G., both of whom were painters, must have known what was at stake in the cashier’s crazy — crazy beautiful — act of self-effacement.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Film Noir, Fritz Lang, Harvard Archive, Jean Renoir, La Chienne, Scarlet Street

Excellent!