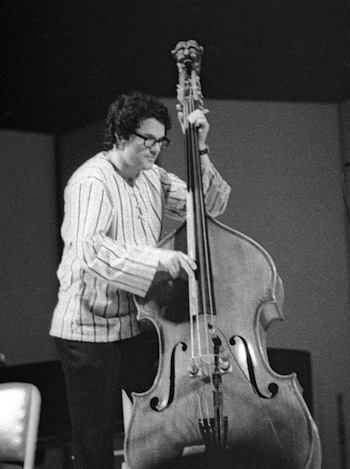

Jazz Remembrance: Bassist Charlie Haden — August 6, 1937 – July 11, 2014

“One of the great things about improvisation is that it teaches you the importance of the moment and how to live in that moment and place importance on this life and making this life better.” — Charlie Haden

By Michael Ullman

On July 11th, the great jazz bassist Charlie Haden died of complications from childhood polio. Although his first recording was made in 1958 with pianist Paul Bley, Haden became famous, at least among the more open-eared jazz fans, with the first Ornette Coleman quartet, which recorded its melodic version of free jazz for Atlantic in 1959. The music, which Coleman described as an adventure, was challenging: after Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry played one of the leader’s compositions, they would improvise without preset chord sequences or phrase lengths.

Haden seemed in many ways the anchor of the quartet. At a time when many bassists, including his friend and sometime roommate Scott LaFaro, were playing guitar-like runs, Haden focused on developing an extraordinarily rich and broad sound. In a 1984 interview with me, he explained his approach: “I’ve always heard music in a way that was more chordal and sustained, with emphasis placed on the importance of a note rather than on the number of notes. There are certain chords in certain songs that evoke beauty. I like to bring out that beauty even more, and in order to do that you have to place importance on each note.” In order to generate that distinctive sound, he kept the strings of his bass higher than most younger bass players. “I say, when you play make your instrument sound as beautiful as possible because when that beautiful sound comes back to your ears it’ll inspire you to play even better.”

Haden was among the most lyrical of modern bass players. He memorably introduces Coleman’s “Ramblin,” a tribute to the bassist’s country music past, and the saxophonist’s remarkable dirge, “Lonely Woman.” He maintained a long relationship with pianist Keith Jarrett, who let Haden play the first chorus (and set the tone) on his 1968 cover of Bob Dylan’s “My Back Pages.” Haden was the bassist (and occasional singer) on Carla Bley’s eccentric masterpiece Escalator Over the Hill. In 1969, he had her arrange his remarkable Liberation Music Orchestra recording, in which he introduces songs from the Spanish Civil War and played his own moving “Song for Che.”

In later years, he led his Quartet West quartet, surprising fans of his freer jazz by performing the standards. He played regularly with guitarist Pat Metheny and recorded gospel hymns with bebop pianist Hank Jones. His most recent recording is a session of duets with Keith Jarrett, the appropriately named Last Dance (ECM). A rapt listener, he excelled in duos. Two of his most remarkable recordings are sets of four duets: Closeness and The Golden Number, both from the ’70s. “When I was in France,” Coleman said about Haden, “I was told a story about musicians [in the past] whose music never had too many beats or too many intervals. But this music is perfect, and it is being performed today. Listen to Charlie Haden’s concept of the “Golden Number.””

Haden’s professional career could be said to have started when he was two years old. Over a rapid succession of cappuccinos, which he ordered two at a time, he told me during an interview about a revealing discovery: “I have a tape from a 1939 radio show in Iowa. I was two and I was yodeling and singing. My dad was the announcer. We had all those different sponsors, like Cocoa Wheats. The theme song was ‘Keep on the Sunnyside of Life.’” His father, Carl Haden, played guitar and sang. In Springfield, Missouri, Carl and his wife hosted their own radio show, Corn a Crackin’. According to Haden, all the country stars appeared: many became friends. Maybelle Carter, of the famous Carter Family, sat in their living room and sang for hours. His dad, though, wouldn’t let his son play along: he insisted on everything being in tune. In a sense, Haden’s ear was trained by singing with others before he touched an instrument. He knew what he wanted to play before he had a bass in his hands: “I think it’s more like discovering the inner voice, rather than the outer voice. You find and discover the harmonies and the melodies and the chords and the intervals that you feel close to.”

Haden was introduced to jazz when his brother brought home recordings by Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Stan Kenton. When he started on the bass, he’d play along to those records. After the family moved to Omaha to start their own television show, Haden taught himself to read music. He met Kenton’s bassists, Stan Levely and Don Bagley. Back in Springfield, he played on a show called the Ozark Jubilee. He started playing jazz with other like-minded country musicians, including a trio featuring guitarist Hank Garland. When it was time for college, he turned down a scholarship to the Oberlin Conservatory. Instead, he went to the obscure Wesley College of Modern Music in California. He had little to say about the experience, but he a lot to say about the music scene in Los Angeles: “I met people and got to play with people like Elmo Hope and Sonny Clark and Hampton Hawes and Dexter Gordon.” Pianist Hope turned out to be the most influential: “He had a really symphonic compositional concept in his playing. He listened really intensely and he placed importance on having a beautiful sound. And waiting, not being so eager, waiting for the right note to make it just sound magnificent.”

Haden went to the sessions in LA and slept little, but he gradually became disenchanted with the rapidly moving chord sequences of bop:

When it came time for the bass solo, sometimes I would hear something to play that was not on the chord structure, but [based] on feelings about the composition or an inspiration from the melody. But in doing that, the solo would evolve in a way where you would create a new chord structure, different from that of the original piece but inspired by it. But whenever I tried to do that people would really grumble under their breath. Then when I met Ornette, he was doing that too.

He and Coleman started rehearsing together, thus beginning a lifelong musical relationship. At first, Haden wasn’t sure what he was doing:

It was just so new. We were just beginning to formulate what we were hearing. And we still are. Every time I play with Coleman, even now, this stuff happens that’s surprising, and you learn from it, because it’s still being formulated and I guess there’ll never be an end to it. It’s a way of improvising that has a desperate kind of urgency for spontaneity that you don’t have with regular, traditional jazz improvisation.

Playing with Coleman, trying to anticipate his lines without mimicking them, Haden learned what it took to be an agile accompanist.

I learned something playing with Ornette that I’ve applied to other musicians. What it is, is that you are playing against another person. Because when you play exactly what they play, or if you play a rhythm that they play beat by beat, it doesn’t add that much. Not as much as if you play against what they’re doing to give it a kind of cohesiveness. Like you complete a picture they’re drawing. By playing against what they’re doing, you’re actually playing with them, except that you’re not repeating what they’re saying.

It’s this aesthetic revelation, or collaborative technique, that allowed Haden – no matter who he played with, no matter what the musical context – to expand the musical vision of others.

A deeply sincere man, he was concerned with politics and what one might call ‘the way of the world’ as well as with the direction of music. He worried about the effect of MTV on his daughters, and liked to hang out with saxophonist Archie Shepp because Shepp would talk politics with him. Music, he believed, could make a difference: it made people pay attention and appreciate the beauty around them. Perhaps that’s why he crafted his tense melodies with such deliberate care: he made every note count because he wanted to make every moment count:

One of the great things about improvisation is that it teaches you the importance of the moment and how to live in that moment and place importance on this life and making this life better. So when I get up on that bandstand, I’m trying to convey this as much as I can in a humble way, in an honest way. Because you really see the importance of being humble when you are up there playing. Music allows you to touch it, and it’s saying to you how much bigger all this is than you are.

Everyone hears music differently. It’s like having different finger prints. Sometimes I hear a sequence of notes that go by rapidly and sometimes I hear notes that are sustained and more slowly played. It’s not a predetermined thing. I always play as if I didn’t know about a concept beforehand. Like there was not such thing as ever as jazz or bebop. I start out completely anew, like I was just born into it or something and you don’t really know anything about the language. But the language is inside you because you grew up loving it, and it’s there and you know it. It’s internalized. It’s realized and you don’t have to think about it any more. Then you can forget about it and pretend in a way like you never heard of it before. That way you are able to really play something that might start a new language.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.