Stage Review: Hershey Felder’s “Abe Lincoln’s Piano” — Hits Some Wrong Notes

“Abe Lincoln’s Piano” does not evoke in us the same sense of astonishment that Hershey Felder feels toward his antiquarian discoveries; his personal serendipities remain dramatically elusive.

Abe Lincoln’s Piano: A New Musical Play by Hershey Felder. Book by Felder. Music by Stephen Foster, Felder and others. Directed by Trevor Hay. Presented by ArtsEmerson, Cutler Majestic Theater, Boston, MA, through May 31.

By Robert Israel

Performer Hershey Felder hopes that the serendipitous encounters he’s had in his life and travels, his chance encounters with the mystical, historical and musical, will duly inspire us. We live in a continuum, he asserts. We need only pay close attention to the seen and unseen in order to arrive at similar connections, to gain similar insights, which will lead us to more awakened, more inspired lives.

Felder’s unifying device is often a concert grand piano, placed center stage, which he plays with mastery and passion. The piano, under his command, creates sensations of an orchestra when he plays it full scale. The instrument can also, when he plays it in hushed reverence, caress our senses as if we are hearing a lullaby. Felder manipulates this range of sound in richly entertaining ways.

It was the piano that Felder first heard growing up in the Montreal of his youth when his Hungarian-born mother sang tunes from the American Civil War songbook. He was already enchanted by this music when he arrived, serendipitously, as an adult at the Chicago History Museum, where he found, in the attic, the actual piano from the White House when President Lincoln was alive, stored there amidst the dust and other artifacts, waiting to be caressed. Mrs. Lincoln, we learn during the play’s first moments, longing to connect to the spirit of her son who died too young of typhoid fever, turned to the music played on this instrument for solace. During a séance with a medium, she and the President reportedly witnessed the instrument levitate, as if possessed.

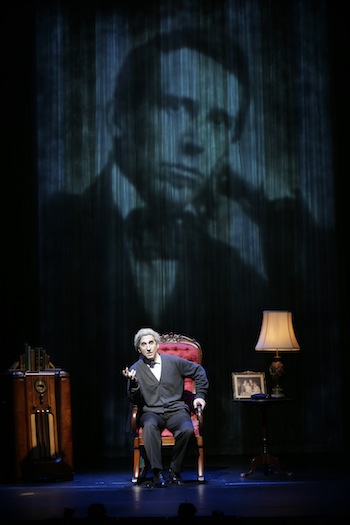

Starting off with that historical episode, Felder then hopes we will become enraptured by other discoveries which clutter the Majestic Theatre’s stage: a mannequin that holds a Union Army coat, a chair cloaked in a cotton shroud, a box containing the blood-soaked sheet from the bed where Lincoln, shot in the back of the head by John Wilkes Booth, lay dying. Felder, in the guise of a docent working for the museum, introduces us to these items, one by one. He eventually transforms himself into Charles Leale, a 23-year-old Union Army surgeon, who ministered to the dying Lincoln on April 14, 1865. The rest of the play takes us on a journey, with Dr. Leale as our guide, back in time.

Alas, the time-tripping doesn’t completely come off. Felder plays the piano with grace and artistry, but the songs from the era are irritatingly monochromatic: melancholic, sentimental, and dreary. Despite clever projections of scenes from Washington, D.C. and other locales, the show does not evoke in us the same sense of astonishment that Felder feels toward his antiquarian discoveries; his personal serendipities remain dramatically elusive.

Essentially, Abe Lincoln’s Piano does not convey any of the mystery that Felder feels is generated when coincidence and supernatural order appear to collide. While we listen to “Beautiful Dreamer,” “Oh! Susanna,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and other tunes, the effect is not a spell-binding return to earlier days. Instead, we are left with a mawkishly cloying aftertaste. Too many doses of cobwebbed nostalgia, along with details of the Lincoln assassination, turns the play’s Americana leaden.

As an artist, Felder’s voice speaks loudest when he is performing at the concert grand piano, playing it with enviable ease. This time around, by morphing into different Civil War era characters, he moves away from his strengths and ends up creating strained historical drama.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com