Visual Arts Review: A Tribute to a Lost World of Joy and Fury — “Loisada: New York’s Lower East Side in the ’80s”

For once, in Ronald Reagan’s America, youthful talent and energy seemed able to trump everything else.

Loisada: New York’s Lower East Side in the ‘80s at the Addison Gallery of American Art on the campus of Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, through July 31.

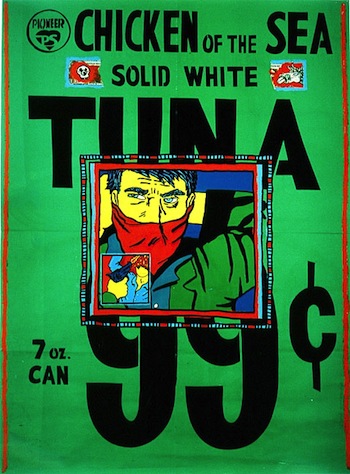

David Wojnarowicz, “History Keeps Me Awake at Night,” 1986. Courtesy of the Addison Gallery of American Art.

By Peter Walsh

Before developers Balkanized it into made-up neighborhoods, the Lower East Side stretched south from 14th Street to Canal and east from Broadway to the East River.

The gritty, teeming district of block after block of cluttered shops and Old Law tenements provided cheap shelter to impoverished immigrants and the down and out — East European Jews, Caribbean Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Ukrainians, drunks and addicts, pockets of stranded Irish, Poles, and Italians. The streets had low numbers. The avenues had no numbers or names at all, just letters, the thoroughfares of Alphabet City, as if their surveyors abandoned hope even before they laid them out. The lettered streets never, ever reached Uptown.

At the center of it all lay the notorious Avenue C, trafficking untold vices, described in Galway Kinnell’s long poem, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World,” as “where the drowned suffer a C-change,/ And remain the common poor.”

By the late ’70s, the northern part of the district had become the “East Village,” its newer residents — students, musicians, poets, hipster yuppies, strangling bohemians, and artists of various stripes — attracted by the low rents and downscale urban atmosphere. As its arty reputation grew, small galleries began to pop up in shops and basements. There were some 200 galleries in the East Village at its peak, as the trendy elbowed out the downtrodden.

Like the rest of Manhattan, the East Village began to attract graffiti “artists.” Their spray-painted tags began to resemble, then influence, and finally become the art on the gallery walls.

By then, diners at hip cafés shared sidewalk space with the homeless and passed-out druggies. For about a decade, until rising rents, drugs, and AIDS brought down the curtain, it was the best show in the city.

The “Loisada” of the Addison Gallery’s Loisada: New York’s Lower East Side in the ’80s, is said to be a Latino colloquialism for “Lower East Side” (“Loisada Avenue” was an alternative name for Avenue C). In political practice, the name claimed the entire district, not excluding its increasingly gentrified, non-Latino enclaves. Presented at this exhibition, though, is a tribute to that lost world of joy and fury, a multi-ethnic, outsider scene where you could go from spray-painting walls to a one-man gallery show in a New York minute and where, for once, in Ronald Reagan’s America, youthful talent and energy seemed able to trump everything else.

All but one or two pieces in the show belong to Andover alum John P. Axelrod, an enthusiastic collector in many areas, from Art Deco to American prints. The selection is inevitably personal and limited. The artists on view are relatively few and all male (no Nan Goldin, no Kiki Smith). Some of the most famous artists connected to the East Village scene are underrepresented or absent (high prices may put their work out of reach). There is also a heavy emphasis on certain themes, homoeroticism and explicit sexuality in general (the show bears the now familiar warnings about potentially offensive content).

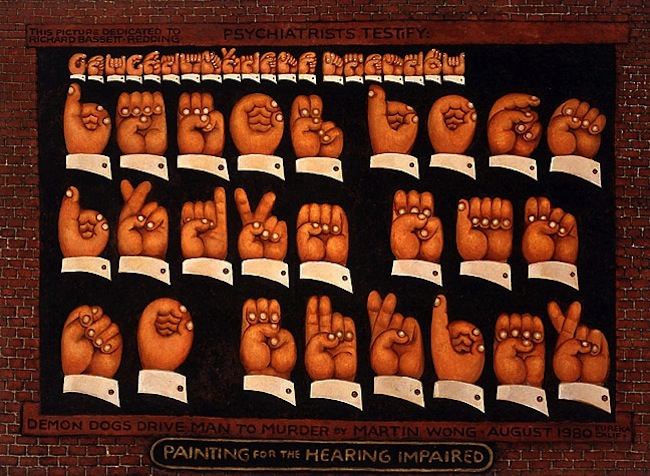

In many ways, the Addison artists, which include David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong, Peter Hujar, Richard Hambleton, and Christ Daze Ellis, are closer to the streets than many of their better-known contemporaries, who sometimes barely touched the sidewalk in their trajectory to art world fame. These artists, misfit, mismatched outsiders all, are an especially good illustration of East Village everything-including-the-kitchen-sink eclecticism: advertising, comic book art, science fiction, pornography, protest art, tabloid headlines, bad dreams, TV, video, poetry, Dada collage, abstract expressionism, the doodles of bored high school kids, and studio class figure studies.

Most art movements are reactions against the older generation. This one paid homage to several at once: Warhol and Pollock, evidently not knowing or caring that, art historically speaking, they were supposed to be polar opposites. They were, after all, artists who came from utter obscurity and near poverty to fame and riches, solely on the strength of their talents. Like the Loisada group, they flaunted American conformity and suggested an alternative: a community of artists against the world.

Martin Wong, “Psychiatrists Testify: Demon Dogs Drive Man to Murder,” 1980. Courtesy of the Addison Gallery of American Art.

There is a lot to see in this show. Here is David Wong’s Stevy, in which two hunky, uniformed firemen kiss in the midst of a star chart, Chris Daze Ellis’s cryptic messages against the city skyline, Richard Hambleton’s sketchy riders, galloping into a darkening Marlboro Country, John Ahearn’s painted plaster portrait reliefs, which made neighborhood characters into icons, David Wojnarowicz’s X-rated roundels, screened from gay porn magazines. The star of the show is also the smallest: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Man), the show’s only Basquiat, in pencil and crayon, dead in a broad-brimmed hat, one hand a child’s cypher, one leg enclosing a grave-digger’s spade.

Here, as in the ’80s, Basquiat stands out.

Before most of us even noticed, it was over. Warhol, Basquiat’s great friend and collaborator, died in 1987; Peter Hujar succumbed to AIDS the same year. Basquiat died in 1988 of a heroin overdose. He was 27. By the end of the century, Martin Wong, David Wojnarowicz, and Luis Frangella were all gone, as were most of the East Village galleries. The center followed low rents further west, to Chelsea. The New York art world became less intense, less focused, less fierce, more concerned with money and the market. Things have never been the same since.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: Addison Gallery of American Art, Christ Daze Ellis, David Wojnarowicz, John P. Axelrod, Loisada: New York’s Lower East Side in the ‘80s, Martin Wong, Peter Hujar, peter-Walsh