Book Review: An Informative Tour of Randy Revolutionary Times

This book is a valuable reminder that “the men associated with an era of supposed morality and Christian values of monogamy and marriage have nearly all been linked to infidelity and sex outside of wedlock.”

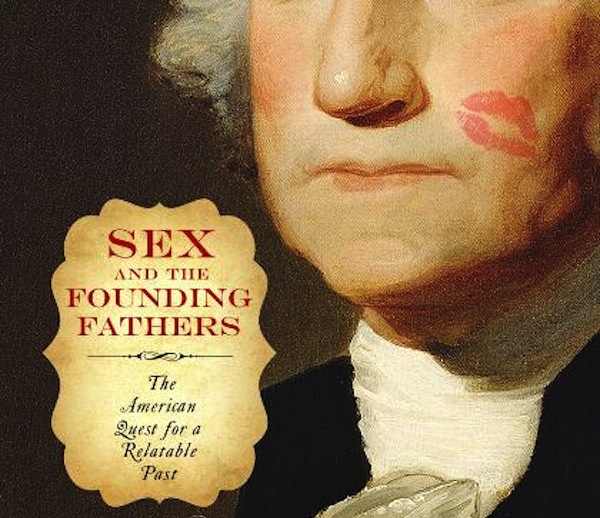

Sex and the Founding Fathers: The American Quest for a Relatable Past by Thomas A. Foster. Temple University Press, 232 pages, $28.50.

By Blake Maddux

Sometimes Broadway gets it right. And believe it or not, it turns out to be about American history! Sex and the Founding Fathers, Thomas A. Foster’s latest book on the significance of copulation in American history, includes a reference to the 1969 musical/1972 movie 1776. Describing a scene in which Thomas Jefferson’s wife unexpectedly arrives in Philadelphia from Virginia, Foster writes, “Jefferson is shown actually taking a break from writing the Declaration of Independence to make love.”

In the musical, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, who have come by at the time of Mrs. Jefferson’s arrival to check on the progress being made on the Declaration, walk away in disappointment. Adams expresses his incredulity at the fact that Jefferson is not only going to (gulp) have sex in the (gulp) middle of the afternoon, but that he is making it a higher priority than fighting the writer’s block that has kept him from articulating the causes that compel the American colonies’ desired separation from Great Britain.

Franklin, who is far more enlightened on such matters, tells his younger companion, “Not everyone’s from Boston, John.”

Although 1776 does not claim to hew closely to historical records, Thomas Foster argues that the film’s depiction of our Founding Fathers sensual proclivities is spot on. Foster describes the real Adams as having engaged in “self-congratulatory prudery” and as one who “took no pleasure in such immoral pastimes — yet took pleasure in their absence.”

Thomas Jefferson, asserts Foster, was as likely as any man to have had blood flowing to somewhere other than his brain while he was struggling to write what is arguably the most important document in American history. (Not surprisingly, most of the book’s chapter on Jefferson is about his relationship with Sally Hemings, the slave who was 30 years Jefferson’s junior and with whom he fathered several children over the course of a 38-year relationship.)

Author Thomas A. Foster — there is a lesson to be learned in his study of sex and the Founding Fathers.

Furthermore, Benjamin Franklin’s freewheeling reputation was such that, after his death in 1790, “the U.S. Senate would not endorse the House’s resolutions in honor of Franklin,” and “[a]t the end of the nineteenth century, when Massachusetts Senator George F. Hoar was given a list of names for the National Hall of Fame, he crossed out Franklin’s name…”

Early in the book, Foster writes that “museums and popular biographers, if pressed, might concede that they use sex opportunistically; a titillating message draws in a wider public for the real history that they want to teach.” Given the title of this book, one might see this as the historian’s preemptive defense against the charge of his having done just that. However, he adds that “the role of sex in history should not be so easily dismissed. The element of sex heightens interest in the histories of the Founders because learning about their intimate lives also personalizes abstract notions of political citizenship and connects Americans to their nation and their own identity as Americans.”

Moreover, the book’s subtitle — The American Quest for a Relatable Past — suggests the author’s decidedly non-titillating historiographical approach. Foster is an Associate Professor of History at DePaul University in Chicago. He is also affiliated with the university’s programs in Women’s and Gender Studies, LGBQT Studies, and African and Black Diaspora Studies. He is the author Sex and the Eighteenth-Century Man: Massachusetts and the History of Sexuality in America.

Of course, non-titillating certainly does not mean bland. Still, Foster’s book is more interesting and informative than it is riveting or groundbreaking.

Each of the six chosen Founding Fathers has one chapter devoted to him. The first five — George Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton — are among the first whom the average educated American would associate with helping to create a new nation. The sixth is, alas, a man whose name has most likely been forgotten by many of the already few to whom it was ever familiar. This is unfortunate because Gouverneur Morris was the man who, as chairman of the Committee on Style at the Constitutional Convention, wrote the Constitution that has been admired for more than two and a quarter centuries. It is to Morris that we owe the immortal words of the Preamble.

Of the common portrayal of the Founding Fathers in art, Foster notes that their sensuality has been downplayed, “their flesh is covered from neck to wrists, with only hands and face exposed. Typically, the men are frozen in advanced age… further confirming their identities as desexualized elder statesmen for generations of Americans who associate sexual activity with youth.”

Of course, they were all young before they were old, and they behaved in a manner customary of young men with wild oats to sow. Moreover, the press was as likely then as it is now to consider it newsworthy when they crossed the line into perceived misbehavior. For example, the Boston Evening Post ran a satirical engraving and poem in the mid-eighteenth century suggesting that Freemasons, who counted George Washington among their members, “engage[ed] in anal penetration with wooden spikes used in shipbuilding.”

While this claim may have been unsupported, the fact is that the sex lives of these distinguished people were topics of common conversation.

Gouverneur Morris was rumored to have wound up peg-legged after “losing his leg while escaping a jealous husband.”

People even joked that Washington might have caught the cold that killed him “from leaping out of a window, pants-less after a romantic encounter with an ‘overseer’s wife’.” Gouverneur Morris, meanwhile, was rumored to have wound up peg-legged after “losing his leg while escaping a jealous husband.” In fact, no lesser a figure than fellow Founding Father John Jay wrote that it would have been better if Morris had “lost something else.”

In the century or so that followed the passing of Washington and company, Foster explains, biographers chose to handle such details delicately. For “memorializers” — as Foster occasionally calls them — of Franklin and Morris, this required disregarding the thorough and explicit diaries that their subjects kept. As early as 1882, however, a historian wrote of Alexander Hamilton’s publicly acknowledged adultery, “The fault which he committed was no uncommon one; that [sic] he was no worse than his contemporaries.”

As the influence of Sigmund Freud cast its shadow over the Victorian Era, however, it became increasingly common to play up the sex lives of men like George Washington, who never fathered any children with his wife. Therefore, he became vulnerable to being slotted into psychoanalytic/Cold War categories, where “childlessness was linked to subversiveness, to ‘pinkos’ and ‘homos’…”

Sex and the Founding Fathers is not the first book to discuss in depth the details of the sex lives of the nation’s founders. Foster is at his most provocative when he traces how public discussions of sex and our American patriarchs have evolved over the past few centuries. Plus, it is as good of a place as any for readers to receive the ever-necessary reminder that “the men associated with an era of supposed morality and Christian values of monogamy and marriage have nearly all been linked to infidelity and sex outside of wedlock.”

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to DigBoston and The Somerville Times. He recently received a master’s degree from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Thesis Prize in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts. He will be teaching a class during the spring term on the First Amendment in American History at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education in Cambridge, MA.

Tagged: Sex and the Founding Fathers: The American Quest for a Relatable Past