Theater Review: “Nalaga’at” (Please Touch) — A Daring Dramatic Struggle Against Absence

By Joann Green Breuer

Theater is a public art. And yet, the irony here is that the most profound communication between individuals can be the least publicly communicable.

Not By Bread Alone, Nalaga’at Theater Deaf-Blind Acting Ensemble. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Paramount Center Mainstage, April 1 – 6. Performed in Hebrew with English surtitles. Cafe Kapish sign language demonstration 40 minutes before each performance in the Randall Lobby. (Closed)

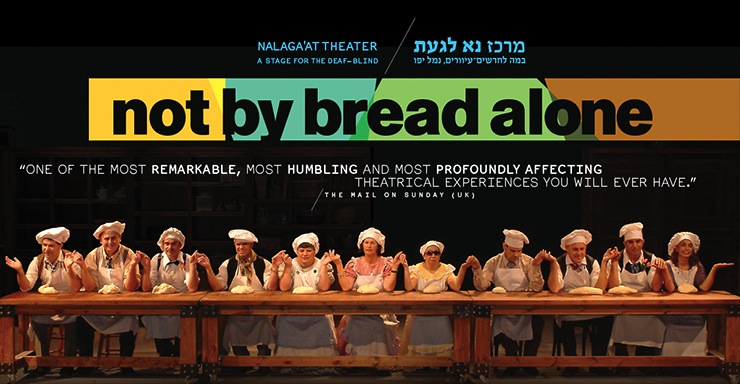

Performers knead and bake bread in “Not by Bread Alone” by the Nalaga’at Theater Deaf-Blind Acting Ensemble. Photo: Nalaga’at Theater Ensemble.

Read Debra Cash’s preview for The Arts Fuse of Not by Bread Alone.

We enter the theatre and see almost all the performers on stage, a row of standing white hatted and aproned bakers facing us, rolling and pounding dough, shaping it into balls, placing them on a long table in front of them, feeling the edge of that table lest the balls roll to the floor, all hands on deck, all hands working, each hand distinct, moving in its own rhythm, forming its unique curves. Music hums, aromas drift. Eventually tin pans are passed down the line, the dough is sent by a team in black to be baked. And then, the familiar, anticipatory moment just before the start of a show: lights out, audience quiet. At Nalaga’at the mind jolts: this is the permanent world of these actors, a world of darkness and silence. Conventional theatrical expectation now is singularly eclipsed by fear.

Director Adina Tal extends the terror: with the stage lit moments later, the performers appear seated downstage, their faces covered by blank white masks. How shall we know them? How will they know us? Does the absence of two of our most obvious senses, sight and hearing, engender anonymity, does the absence of these senses imply absence of individuality, ultimately absence of personhood? Not By Bread Alone, the show which follows, is a daring dramatic struggle against that presumption.

One after one, the performers remove their masks. Each actor offers a sliver of autobiography, often containing, but not necessarily, revelations of a lack of sight and hearing. For some, the fact is given at birth; for others, sometime later, by gradual genetic anomaly or subsequent disease. Deaf/Blind is a fact, but not the only fact of their lives. This is a perspective which we temporarily able-bodied audience are asked to remember, and which the art of their theatre aims to prove. And it does.

The program is a series of vignettes, some humorous, some romantic, all touching – pun intended. The conventional distance between strangers must be breached if communication is to succeed within this remarkable troupe.

And yet, somehow, the awareness of community is often achieved in their sensory space, and with it, surprising confidence.

Language is, for the audience, a mishmash of American and Hebrew sign, spoken Hebrew, Russian, English, English supertitle projection (Itshak Hanina at the Braille writer), mime, gesture, and facial and corporal expression. Stage movement is memorized (paces in the invisible world), or assisted by black clad interpreters who signal ‘action’ with the thud of deep drums. The latter occasionally lead the actors with a single touch at the shoulder or a sustaining arm. The interpreters are designed to be inconspicuous as possible, as minimally present as can be conceived. This is the eleven actors’ show: their challenges, their lives, their wishful, seemingly impossible fantasies, their all-too-human humanity, and unpredictable humor. Pathos be damned.

Scenes speak, with skill and albeit well-rehearsed spontaneity, of soccer and singing, sun-rayed swings and clowning around, sophisticated hairstyles, super-sized containers of popcorn at the movies, women’s sewing circles, death of a youth, drenching rain under colorful umbrellas, and, finally, raining rice at a wedding under a white chuppa. It is in this climactic sequence that one truly approaches some minimal understanding of the vital source of life as Deaf/Blind.

I have directed plays among the ASL community. What struck me at first and thereafter as I baby-talk my basic sign language is how impossible it is to utter untruth when someone is watching closely. As a corollary, I am aware how one must pay constant attention to the signer. To look away is to lose context, and to be blatantly rude. The romance portrayed on stage in the final scene of Nalaga’at extends this intimacy of communication, making it more than a theatrical metaphor. This vision of communication is bounded in trust. It is intrinsically private, like love.

Speech for the Deaf/Blind is necessarily tactile. There are various methods of hand to hand language, each involving the offering of one’s hand in another’s. We know that the hand can be dangerous. Close up, we shake hands with others to prove that we hold no weapon; at a distance, we wave open-handed to announce our weaponless presence. As the on-stage wedding, and the performance concludes, the newly married couple reach to each other and speak with each other. Their hands commingle. There is no interpretation. We cannot see within their palms. Even if we knew the code, few of us would be able to read their words. Nor should we. Theater is a public art. And yet, the irony here is that the most profound communication between individuals can be the least publicly communicable. There is a lesson here, and one that perhaps only a Deaf/Blind theatre could teach so simply and with such courage and delight.

After the curtain call, the audience is invited to share the aromatic, freshly baked rolls, and to dare to touch the hands that have guided us through our own amazement and apprehension to the heart within each of us and them. Bravo.

Joann Green Breuer is artistic associate of the Vineyard Playhouse.