Book Review: Pierre Michon and his Many Artistic “Lives”

The books are bleak in that Pierre Michon provides no reassuring, idealistic view of the creative urge. Art leads to no transcendence, no permanent uplifting sentiment. Making poems or making pictures is a rough daily business.

Small Lives, translated by Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays, Archipelago Books, 215 pp., $15.

Rimbaud the Son, translated by Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays, Yale University Press (Margellos World Republic of Letters), 96 pp., $13.

The Eleven, translated by Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays, Archipelago Books, 97 pp., $18.

Masters and Servants, translated by Wyatt Mason, Yale University Press (Margellos World Republic of Letters), 177 pp., $13,.

The Origin of the World, translated by Wyatt Mason, Yale University Press (Margellos World Republic of Letters), 93 pp., $13.

Winter Mythologies and Abbots, translated by Ann Jefferson, Yale University Press (Margellos World Republic of Letters, 117 pp., $13.

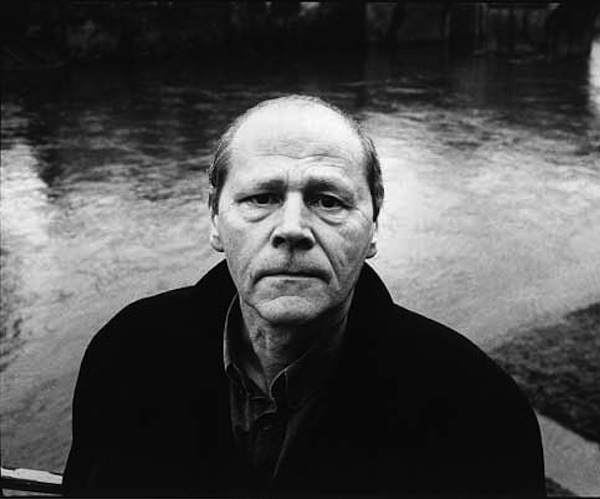

By John Taylor

The French writer Pierre Michon (b. 1945) enjoys a rare privilege in our country that translates so little: all his work has suddenly become available in English. After the publication in 2008 by Archipelago Books of Small Lives (1984), the striking memoir (and his first book) that established his high critical reputation in his homeland, the same press and now Yale University Press have combined forces to issue all his subsequent volumes to date.

This initial title (Vies minuscules in the original) defines a literary approach that sums up his oeuvre. His later books, which can mostly be described as novellas or as collections of novellas (or stories), are also “lives.” By focusing on figures such as Rimbaud, Van Gogh, Goya, and Watteau, on lesser known artists (such as obscure disciples of Claude Lorrain and Piero della Francesca in Masters and Servants), or on the fictional French Revolution painter “Corentin La Marche” who is portrayed so memorably in The Eleven), Michon has revived the classical “vita.” Like Plutarch, Suetonius, and Vasari, he attempts to capture the essence of an existence and a vocation.

This genre is not unique with him in contemporary French literature. It has been practiced with equal brio by Pascal Quignard (b. 1948) and Michèle Desbordes (1940-2006), who have similarly encapsulated artistic lives. Among his several other books and short prose texts in this vein, Quignard is admired for his portrayals of the Baroque viola da gamba composers Marin Marais and Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe in All the World’s Mornings. Desbordes is the author of a moving re-creation of Leonardo da Vinci’s last three years in Blois (The Maid’s Request), not to mention her gripping (and still untranslated) account of the sculptor Camille Claudel (La Robe bleue).

Like Michon’s intense prose depictions, these literary works are based on rigorous documentation yet are also informed by how the French conceive biography. As opposed to the biographie à l’américaine, in which the biographer details not only significant events, but nearly every other “fact” that crops up during his research, a French biographer typically isolates only those facts enabling him to capture the central thread or motivation of a lifetime. In this respect, Michon seeks to highlight what might unify an artistically creative life, all the while raising the deeper question: is there unity in any life?

This question aside, there are no blatant philosophical underpinnings in his books. There is no political engagement, which is not to say that social commitment is lacking. The adjective “small” or “minuscule” used in the title of Michon’s autobiographical first book expresses his compassion for the lowly. As he discloses in that text, he himself came from an impoverished social milieu and region: the Limousin. His subsequent stories about artists also often include characters of lower social status. This is the case of Van Gogh’s friend, the postman Joseph Roulin, in the novella that is in fact entitled not “The Life of Vincent Van Gogh,” but rather “The Life of Joseph Roulin” (Masters and Servants). The novella is a moving double portrait of an improbable friendship.

Michon, moreover, describes the difficult material conditions of some of the artists whom he studies, detailing their struggle to survive through commissions granted by the wealthy. The stories are not only about creativity per se — the task of accepting and carrying out one’s artistic calling — but also about creative activity within the strictures of a given socio-economic structure. The author also describes exceedingly well daily exigencies and their impact on creativity. Evoking absent fathers and delving into the turmoil of the artistic vocation, several stories parallel the trajectory of Michon’s own coming of age as a writer, as delineated in Small Lives. At the same time, it is unnecessary to have read that book in order to fully appreciate the historical narratives.

His books are (or contain, as with the collections Winter Mythologies and Abbots or Masters and Servants) compelling stories composed in a distinctive style. The language even sometimes draws on archaic syntax, a structural element that gives resonance to his writing, as if it were emanating from several centuries of French literature— which is the case — and not just the colloquial idiom of our day and age.

In contrast to many French prose writers of similar stature, he is a realist. He uses precise terms for objects and closely observes human acts in an effort, not only to be historically accurate, but also and especially to convey sense impressions. In French and now in English, his writing is lush and sensate. It is not surprising that he has written essays about realist mentors such as Honoré de Balzac and C. A. Cingria (1883-1954), the latter an unclassifiable Swiss author—alas, unknown to American readers — with a style that brilliantly (and humorously) conveys a multitude of sense impressions. Although Michon’s style cannot be described as humorous, it has a matter-of-fact, sardonic, disabused tone all its own. He is likewise an avid reader of Faulkner, who has probably exerted the key influence on him.

While reading these fine translations of books that I had already read in French, I was struck time and again by how natural Michon seemed in English. This compliment to the translators is by no means meant to diminish the difficulties that they faced. In his introduction to The Origin of the World, which differs from the other books (and, although fictional, somewhat recalls Small Lives) in that it is a grim love story set in 1961 not far from the prehistoric caves of Lascaux, Wyatt Mason rightly points to Michon’s “maximal” prose. His “sentences have a Faulknerian heft,” notes the translator, “not infrequently running densely down a full page, grammatical subjects or objects held in suspension until the sentence’s very end, the reader stockpiling the freight of Michon’s accumulating clauses until being delivered to a destination the drama of which only grows with each deferral of arrival.”

In his afterword to the same book, the critic Roger Shattuck offers this apt description:

Michon’s prose tends to slow down in order to oblige you to hear its rhythms and also to see and touch and smell what is happening beneath it. He strives simultaneously for an opaqueness that calls attention to the verbal coloration of the prose and for a transparency that reveals a “real” sensuous world. In Renaissance painting, such a fusing of surface and depth emerged with the development of glazes — layers of varnish that one both sees and sees through. In his best narrative and descriptive passages, Michon gives the effect of a painter building up his glazes. Out of flatness he creates high relief.

Shattuck, however, goes on to argue that “Michon is unwilling or unable to take himself seriously enough to put together a full show — say, 200 pages of continuous narrative.” This is missing the point. Michon’s propensity to stylistic density induces him to write only relatively short prose: portraits, not panoramas. The texts range from the brief legends and tales about various historical personalities — some going back to the Dark Ages — in Winter Mythologies to the novella-length evocation of “the considerable passerby” (Rimbaud the Son) or to the haunting stories about artists in Masters and Servants. Offering the long view, as would a novel, of life as a concatenation of a great number of events between birth and death would not suit his stylistic inclinations. Instead, he focuses on a handful of scenes and musters his exceptional style — arguably, closer to the prose poem than to narrative prose — in an attempt to make them at once palpable and emblematic. Nothing is diluted; these are heady, compassionate distillations — like cognac.

Pierre Michon — his propensity to stylistic density induces him to write only relatively short prose: portraits, not panoramas.

What can be criticized in such polished writing? Its very polish, which sometimes dazzles, momentarily blurring our view of the protagonists? Its historical circumscription (ever since Small Lives and excepting The Origin of the World), which perhaps keeps something essential at a distance? Does something redoubtable, insupportable, remain half-hidden beneath the surface of Michon’s style? But this is no drawback — au contraire. The books are bleak in that the author provides no reassuring, idealistic view of the creative urge. Art leads to no transcendence, no permanent uplifting sentiment. Making poems or making pictures is a rough daily business. So why make them? There are no redeeming horizons awaiting these artists, only an irresistible necessity. Such are the “old verities” of the human heart, as Faulkner puts it, especially of the artistic heart, and Michon examines them acutely.

John Taylor is the author of the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction Publishers, 2004, 2007, 2011), the first volume of which includes an essay on Pierre Michon. He has recently translated books by Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Jacques Dupin, and Louis Calaferte. He is also the author of seven books of poetry and short prose, the most recent of which is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012).

Tagged: Archipelago-Books, Masters and Servants, Pierre Michon, Rimbaud the Son, Small Lives, The Eleven, The Origin of the World, Winter Mythologies and Abbots, contemporary French fiction, fiction-in-translation