Concert Review: Pianist Stephen Hough Dazzles in Rockport

Stephen Hough’s performance of piano works by Brahms and Chopin was enthralling, poetic, and spellbinding.

Pianist Stephen Hough — his unique array of talents has not gone unnoticed. In 2001, he received the first MacArthur “Genius Grant” given to a classical musician. Photo: Andrew Crowley

By Susan Miron

As far as I know, no performing pianist has a resumé with as many impressive accomplishments in as many varied fields as Renaissance man Stephen Hough. The winner of a prestigious Naumberg International Piano Competition when he was 22, Hough has enjoyed a major career as a concert pianist. In the late ’90s, he began to compose chamber and piano music (his Broken Branches CD is quite lovely), while maintaining a active writing career as a prize-winning poet, contributor to London’s The Guardian and The Times as well as a popular cultural blog for The Telegraph. A famously gay Catholic, he has written extensively about theology. He also is an acclaimed painter who had a very well-received exhibition in London’s Broadbent Gallery in 2012.

Hough’s unique array of talents has not gone unnoticed. He received the first MacArthur “Genius Grant” given to a classical musician in 2001, and has been named as one of twenty living polymaths by The Economist, and, in January, was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

It is always a treat hearing music at the intimate Shalin Liu Performance Center, home of Rockport Music. The concert hall’s window on harbor, the summer backdrop of the ocean, boats and swimmers, was replaced on Friday by a darkness that reflected the many lights in the hall. It felt wonderfully salon-like, and the many volunteers were unusually friendly. Everyone was smiling at intermission – had I escaped the winter doldrums by driving only 50 miles?

Hough devised this recital to feature two parallel progressions: from smaller to larger compositions and from the non-pianistic to the super-pianistic. In the recital’s first half, he chose music by composers who generally wrote much larger works in length and in scope. “Schoenberg, Straus, and Wagner could play the piano but were not pianists,” hough explained. “Bruckner was an organist with limited keyboard skills, and Brahms was basically a former pianist – by all accounts rather clumsy at the keyboard and more so as he grew older. On the other hand, Chopin’s music and the instrument for which it is written seem melded together in a uniquely inspired union. No other great composer was so limited in output, yet few have been more influential. Chopin dug at one mine only, but every handful spilled over with diamonds.”

Arnold Schoenberg’s very brief (six minute) Sechs kleine Klavierstücke (1911) (“Six Little Piano Pieces”) is made up of intimate miniatures. The sixth was written upon hearing of Mahler’s death. Played sensitively, it was an inspired and extremely unusual opening, a bit like squeezing an opera into just a few notes.

“So, you survived the Schoenberg!” Hough quipped from the stage. But the audience seemed to relish not just the Schoenberg, but all of the pieces performed during the first half. Next were three pieces I had never heard – or heard of – by very famous nineteenth century composers: Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Richard Wagner (1813-1883), and Anton Bruckner (1824-1883).

Hough was an excellent tour guide to these works. Strauss’s 3 minute “Träumerei” (Op. 9, No.4) had a hypnotically lovely melodic line, with lots of arpeggiation, presaging the rapturous Lieder that he would write later in life. The splendid Albumblatt in C Major: In das Album der Fürstin Metternich WWW 94 by Wagner, also 3 minutes, was a small musical favor the composer (whom we associate with very long operas) whipped up for the Princess Pauline Metternich. She later helped finance the staging of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser, which took place the same year that Wagner put this small musical favor into her souvenir album.

Anton Bruckner composed very few short pieces. The 4-minute Errinerung (“Memories”) was composed when Bruckner was in his mid-forties. Like the Strauss piece, which presented the musical mind of a man who would to on to write major songs, the Bruckner has a dramatic middle section that begs to be re-scored as a symphony.

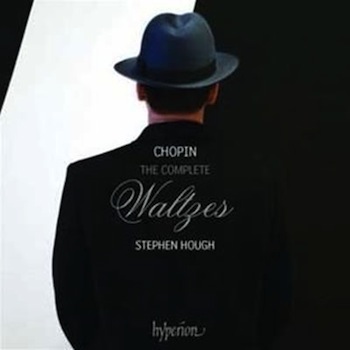

Johannes Brahms’s late piano works, Op. 116, 117, 118, and 119, are among the greatest of not just his piano pieces, but of anyone’s. Virtuosic minatures, about three minutes each, the “Fantasien, Op. 116” begins and ends with Capriccios in D minor, inside of which are another Capriccio and four Intermezzi, the latter a form that Brahms handled brilliantly. Hough’s performance of these works was enthralling, poetic, and spellbinding, which also describes his post-intermission playing of Frederic Chopin’s (1810-1849) gorgeous Four Ballades, Op. 23, which lasts about 26 minutes, but which, in Hough’s hands, supplies enough pleasure for a good month. Composed between 1831 and 1842, these Ballades were given thrilling performances; Hough plays Chopin as well as anyone. I bought his CDs of the Chopin Waltzes (which has won several awards) and of the Four Scherzi and Four Ballades. The two discs are enormously impressive and exciting.

Rockport is to be commended for bringing Hough to New England. Next year, he will be part of Boston’s Celebrity Series. Try to be there. He’s quite wonderful.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 20 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. She is part of the Celtic harp and storytelling duo A Bard’s Feast with renowned storyteller Norah Dooley and plays the Celtic harp at the Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital.