Fuse Theater Interview: Israeli Playwright Motti Lerner on Catharsis, Tikkun, “Hard Love,” and Protesting a Play Without Reading the Script

“The working relationship is based on the mutual feeling that all three of us have the same understanding of the purpose of the theatre – to present plays that create a cathartic experience for the spectator, which might open his eyes and his heart to a new consciousness.”

By Ian Thal

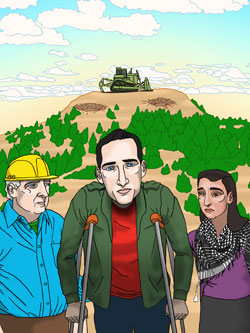

Poster for “The Admission” — a Motti Lerner play receiving a workshop production from Theater J in Washington D.C. later this month.

Israeli playwright Motti Lerner is among Israel’s most acclaimed living playwrights, having received numerous honors, including the Prime Minister of Israel Award for Writers in 1995. At the same time, he is also one of his country’s more controversial playwrights, with several of his more politically charged scripts being performed in translation to English and German speaking audiences before appearing in Israeli theaters.

Most recently, Lerner has been at the center of a controversy around his play, The Admission, which explores an investigation into an alleged atrocity during the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. While the script notes that “The Arab village of Jirin, that is mentioned in the play, never existed; it is merely a parable,” an ad-hoc group calling itself Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art, has been protesting the scheduled staging (from March 20 to April 6) at Theater J in Washington, D.C. What was slated to be a full production has now been scaled back to be a workshop.

Lerner was last in Boston two years ago for a workshop presentation of At Night’s End, a play set during the 2006 Second Lebanon War, presented by Israeli Stage, and directed by Melia Bensussen. This time, he will again work with Bensussen and Israeli Stage on a staged reading of Hard Love.

Hard Love, originally written in 2003, is the story of a divorced couple attempting to reconcile after their children from their subsequent marriages become involved. Hanna (Dakota Shepard), however, is a member of Israeli’s Haredi community (known colloquially as the “Ultra-Orthodox”) which Zvi (Mark Cohen) rejected decades ago when he embraced secular society. The story was sparked by Lerner’s own brief encounter with a former lover who had embraced Orthodox Judaism, as well as his own brief temptation to join with a group of Breslav Hasidim with whom he had become involved while living in the Mea Shearim neighborhood in Jerusalem early in his theater career.

Lerner is also a prolific writer of screenplays and essays, his book length study of Anton Chekhov’s writings, According to Chekhov, was recently translated into English though it is not yet published.

The interview was conducted through an exchange of emails between January 31 and February 16. For thematic reasons, chronology of the questions and answers has not been strictly observed. An Arts Fuse interview with director Melia Bensussen about the reading is posted here.

The staged reading of Hard Love will be presented at the Goethe-Institut on Sunday February 23, at 2 p.m. At 5 p.m. Lerner will be present for a question and answer session.

Arts Fuse: This is the second time that you will have come to Boston to work with both Israeli Stage and director Melia Bensussen. How did this relationship begin, and more importantly, how would you characterize it?

Motti Lerner: I met director Melia Bensussen in 2006 in Center Stage Theater in Baltimore. She was directing a show there, while my play The Murder of Isaac [a play about the 1995 assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin] was being performed. I found her a very deep and passionate director, and I was looking forward to the opportunity to work with her. A few years later I offered her a new play, At Night’s End. She thought that Israeli Stage is the right venue for exploring it and introduced me to Guy Ben-Aharon – its artistic director. I think that the working relationship is based on the mutual feeling that all three of us have the same understanding of the purpose of the theatre – to present plays that create a cathartic experience for the spectator, which might open his eyes and his heart to a new consciousness. I also think that all three of us share strong Jewish identity and we feel committed to the challenges this identity presents to us.

AF: You have often described your aim on one hand, as creating “catharsis” – which harkens back to the ancient Greek tragedians – as well as an act of Tikkun Olam, which is associated with Jewish thought and is usually translated as “repairing” or “healing the world.” For a playwright, how do these two movements relate to one another?

Lerner: I think that creating a catharsis for the spectator is a means for Tikkun Olam. The catharsis is perhaps the strongest tool at the hand of the playwright to create a change inside the spectator. This change purifies the spectator and strengthens him so he can participate more fully in the repair of his own world, which is a step towards the repair of a larger world.

AF: Hard Love addresses the relationship between a Haredi woman and her ex-husband who has left the community for a secular life. Recently, American Jewry has been fascinated with stories of ex-Haredi “leavers,” while at the same time there’s also been a politely distant relationship between the Chabad-Lubavitch sect and the larger Jewish community. However, in Israel, there have been ongoing tensions between Haredi and the rest of Israeli society on issues ranging from national service and economic participation to the role of religion in the Jewish state.

What tensions did you hope to explore between these two very different Jewish identities? What sort of dialogue has it opened up for Israeli audiences?

Lerner: The play explores the tension between a woman whose faith is deep and unshakable and lives with strong presence of God in her life, and a man who rejects any presence of God and struggles to strengthen his own sovereignty over his life. As in most plays, this is a very personal tension between two private individuals who want to live together, but, of course, it serves as a metaphor for the Israeli society – where a big part of it prefers to live according to laws made by human beings according to their changing human needs, and another part in it lives according to laws that where created by religious authorities for eternal religious purposes – where the focus of our consciousness is the worshipping of God and not the needs of the human being.

AF: How have Israeli audiences reacted to Hard Love? Did it spark any of the conversations you hoped it would? Have there been reactions from the religious community?

Lerner: It’s hard to generalize the response. Ultra-Orthodox don’t often go to the theatre very often, so it was difficult to discover their responses. Some of them did come. They find it hard to have empathy for Zvi, who left their community and betrayed them. They also find it hard to accept his criticism of life in their community. Most of the audience members were secular and they were surprised at the end by the fanaticism of Zvi as opposed to the tolerance of Hanna.

AF: Having had several of your plays presented in the United States, what differences do you see regarding the role of the playwright in Israeli and American theater?

Lerner: It’s hard to generalize about the role of the playwright, because each playwright tends to define his role in a different way. I believe that the role of the playwright is to create a public discourse about phenomenon which threaten us as individuals and communities. The playwright must ring an alarm, but the cathartic experience he offers must strengthen the spectator to face these threats more honestly, more courageously, and with deeper solidarity with others in his community.

AF: When you were last here, for a reading of At Night’s End, you had mentioned that the play, which is set in 2006 during the Second Lebanon War, had not yet been produced in Israel. Has that changed? What has the reception been?

Lerner: At Night’s End hasn’t been produced in Israel yet, but hopefully it’ll be produced next season. I must admit that the last two decades were not particularly good for political plays in Israel. It seems to me that most theaters felt more secure sticking to the political consensus and hesitated to present challenging political materials.

AF: Your work has attracted controversy here in the United States. Most recently an ad-hoc group calling itself Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art has, without reading the script, called your play The Admission “anti-Israel.” The group has been organizing a campaign against Theater J in Washington, D.C. for their decision to produce the play, as well as against the D.C. Jewish Community Center and the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington for their support of Theater J.

Likewise, when I reviewed the presentation of At Night’s End here in Boston, a colleague of mine,\ castigated me at length because, in his view, any play by an Israeli playwright, (especially because there was some support from the Consulate General of Israel to New England) was Israeli government propaganda.

While your work has been controversial in your homeland, it has also been widely praised by figures from across the political spectrum, and your work has been presented both by the national theater, Habima and such municipal theaters as Cameri and Herzliya. What do your American critics misunderstand about the relationship between the arts, politics, and government in Israel?

Lerner: I’m not sure that my American critics – among them is the ad-hoc group calling itself Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art – understand my impulses to write plays which will create a process of repair in the Israeli society – a repair which will lead us to becoming a more liberal, more pluralistic, more tolerant, and more free society. This is a constructive impulse that stems from my deep commitment to the Israeli society and from my strong belief that it is legitimate and has the right to continue flourishing peacefully alongside its neighbors and to develop into the idealistic state for all its citizens that its early founders struggled to establish.

I’m appalled by the fact that my play The Admission was attacked so ferociously by Jewish organizations who didn’t bother to read it. I also believe that those who saw At Night’s End don’t regard it as propaganda – the fact that it wasn’t produced in Israel yet proves how critical it is of the destructive policies of some of our governments.

I hope that more Israeli playwrights will resume their responsibility for creating more and more radical plays and these play will be produced by all theaters and will question and doubt and warn, and in this way will participate in the repair process we so badly need.

AF: Having already seen At Night’s End, it was hard to take COPMA’s caricature of you as “anti-Israeli” very seriously – likewise it was easy to not to seriously consider the accusation of propaganda offered by my colleague. You pinpointed a very complex, and often tragic, relationship between the institutions of the family, the military, and civil society. The pressures seem to be to either avoid the political entirely, or to be a propagandist for one side or another. How does a playwright avoid those pressures?

Lerner: The choice of the subject matter for a play is usually based on the fear of the writer that there’s a threat – personal, social or political-ideological – hidden in the subject matter, and therefore the writer must reveal it. I would even say that the writing of the play is based on the feeling – which is probably an illusion – that the play will enable the society to confront that threat. This illusion is necessary for the writer, because otherwise he wouldn’t be able to invest so much effort in the writing. In other words I don’t think that I choose the subject matter, but the subject matter forces itself on me through the threat it contains. Once I yield to it and begin the writing, I’m doing my best to explore the characters, their actions, and their relationships in the deepest layers of their human experience I can reach – this experience exists in the socio-political context which is included in the exploration.

I hope that’s clear.

AF: Let me, rephrase my last question: you mentioned earlier that you feel that a lot of Israeli playwrights are avoiding writing radical plays and Israeli theaters are avoiding stepping outside of current political consensus. One certainly sees a similar phenomenon on American stages– most of our “radical” theater plays it safe by playing only to a narrow constituency.

How does a playwright resist the pressures to avoid catharsis and instead, entertain?

Lerner: That’s a great question. I wish I had a good answer. Partly it’s because of my strong interest in the political-ideological and social life, partly it’s my feeling of responsibility for the events that are taking place around me, part of it is the growing up in a society that created itself, struggled for its survival, and has always faced existential, political and moral dilemmas that have had a tremendous impact on my life as an individual and as a member of a community, and part of it is probably the naïve faith that writing a play can contribute to making a community a better society.

Ian Thal is a performer and theatre educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere, and on occasion served on productions as a puppetry choreographer or dramaturg. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and is currently working on his second full length play; his first, though as-of-yet unproduced, was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. Formally the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report

Tagged: Hard Love, Israeli Stage, Melia Bensussen, Motti Lerner, The Admission