Theater Interview: Stage Director Melia Bensussen on “Hard Love,” and “The Cherry Orchard”

“There is a struggle in love in the best of circumstances, and when on top of the daily challenges there are divisions of culture or society or simply of invented categories – well, that does make it all the harder.”

By Ian Thal

Melia Bensussen is not unknown to Boston theater audiences. The director – who chairs the Performing Arts Department at Emerson College – has staged works for numerous companies in New England and nationwide, receiving such honors as the prestigious OBIE, as well as both the IRNE and Elliot Norton Awards.

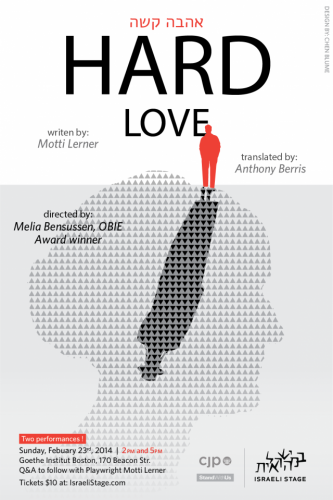

Local audiences have a chance to get a double dose of Bensussen’s work this month as she directs both the Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s production of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, through March 9th at the Dane Estate at Pine Manor in Chestnut Hill (see Arts Fuse review), as well as a staged reading of Motti Lerner’s Hard Love for Israeli Stage at the Goethe-Institut in Boston on February 23.

Bensussen’s previous credits with ASP include Twelfth Night, The Taming of the Shrew, and The Merchant of Venice. She previously worked with Motti Lerner and Israeli Stage on a workshop presentation of At Night’s End.

The interview was conducted through an exchange of emails between January 31 and February 15. For thematic reasons, chronology of the questions and answers has not been strictly observed.

Arts Fuse: As a director who works with both classic and contemporary plays – sometimes with the playwright in the room as part of the developmental process – how do these two tasks inform one another?

Melia Bensussen: A wonderful question. I think they both speak to finding a true reading of a text – and by “true” I mean not only trying to uncover a writer’s intentions, which clearly is not possible without the writer present to confirm them, but to understand the structure and substance of a work. Cherry Orchard is extraordinarily revealing in this way. Chekhov once famously wrote that if there’s a gun in the first act of a play it must go off in the fourth act: his text reflects this in every way! Every idea and emotion that is set up in the first act reaches fruition by the fourth. He is a remarkable writer for the theatre, and the depth of his understanding of the art form is humbling.

AF: You’ve been working with composer and ethnomusicologist Hankus Netsky along with Robert Brustein in developing a musical theater adaptation of the Israel Zangwill novel King of the Schnorrers (scheduled for a production at The New Repertory Theatre next season). Given that The Cherry Orchard refers to the presence of a band of Jewish musicians throughout the play, has this collaboration had an influence on the current production?

Bensussen: Hankus is such a gifted artist that simply working with him on Schnorrers will influence much of my work for years to come. The references to the Jewish orchestra in Cherry Orchard are only in the 2nd and 3rd acts, and they’re touched on lightly. However, Hankus was generous in sharing with me some of the recordings of his Klezmer Conservatory Band, as well as his insights into the period (1904) and styles of music.

AF: Chekhov set The Cherry Orchard during a time of economic and social upheaval in pre-Revolutionary Russia after the serfs had been emancipated. The new middle class is supplanting the aristocracy, which finds its pampered lifestyle no longer economically viable. What resonance does that story have today in the midst of the so-called Great Recession, a time when we are seriously talking about the decline of the middle and working classes, and the ascendency of the so-called 1%?

Bensussen: I think you’ve answered that question yourself simply by asking it, don’t you think? Yes it’s deeply relevant in terms of systems changing and forms of economic life shifting. Also the increase in our American sense of class – the biases of the New Aristocracy, as well as our own sense of class-warfare, make the play relevant. But more than that for me is the emotional journey of the work. At one point one character says, if you spent all the time you spend thinking about money on other things you could change the world. Isn’t that a wonderful and idealistic thought?

AF: It’s easy to present Lopakhin as the villain, who eventually purchases the Gayev estate out from underneath the family. However, acknowledging that it’s usually bad form for an interviewer to discuss his or her own personal history, I find him very sympathetic in his third act victory over the Gaevs; he now owns the house of the family that oppressed his ancestors. Similarly, I grew up Jewish south of the Mason-Dixon line: the original owner of the house my parents raised me in had a restrictive covenant placed in the deed that barred “Jews and Negros” from residing in the building. I know that they take great satisfaction continuing to defy the original owner’s wishes. So what should a contemporary American audience make of Lopakhin?

Melia Bensussen during the Q&A following the Israeli Stage reading of Motti Lerner’s “At Night’s End.” Photo: Q Lam.

Bensussen: The genius of Chekhov is he doesn’t take sides.They are all right, all human, and all have a valid point of view. I love Lopakhin and feel for him – remember, what he tries to do for most of the play is to convince Raneskaya (Lyuba) and Gaev to figure out how to save the orchard themselves. He wants their adjoining lives to continue in some fashion – but it’s so hard for any of us to face reality, to face our circumstances, and to take the appropriate actions to move forward, especially if these adjustments require us to drastically rethink our choices.

AF: I know that we discussed this briefly last year when we spoke, but can you relate how you first came to work with dramatist Motti Lerner?

Bensussen: I’ve known about Motti’s work for years, first wanting to work with him when I saw a production of his play The Murder of Isaac at Baltimore’s Center Stage where I was directing Eugene O’Neill’s Ah Wilderness!. We finally got to meet at a conference in NYC a few years ago, and thanks to collaborating with Israeli Stage we had the opportunity to work together at long last.

AF: This is your second time directing a reading of one of Lerner’s plays for Israeli Stage. Why do you think his work is important? Not just for those in an Israeli context, but for Jews living in the Diaspora, and, for that matter, non-Jewish theater audiences?

Bensussen: The simple answer is because he is a very good playwright. His works sparkle with humanity and insight, and he’s not afraid to spell out the flaws and frailties in people, in ideas, in governments. Coming from a place of complicated politics, he is also subtle in his arguments: he is sophisticated in his approach to plot and character, and like the great Greek playwrights who wrote plays to vivisect history and contextualize the present reality, Motti is able to do the same with his works.

AF: Two years ago, you directed Lerner’s At Night’s End which is set during the Second Lebanon War and explore how the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict affects both the family and the political culture of Israel. In contrast, Hard Love focuses on the relationship between a Haredi woman and her ex-husband, who had left her many years back for a more secular life. How does the play explore the tensions between these two very different types of Jewish identities? As someone with both Sephardi and Ashkenazi heritage — and sometimes muses about having two religions, Judaism and theater — do you see a personal parallel with the tensions that the play explores?

Bensussen: Well, that is a leading question, isn’t it? But yes, I do see parallels in Motti’s work and in my own life. He is able to show us the in-between-ness of life, if you will. The places where we are not one thing nor another – not a good soldier, not a good husband, the confluence and blending of those roles in At Night’s End – and the split that drives the characters apart in Hard Love. The title tells us so much. There is a struggle in love in the best of circumstances, and when on top of the daily challenges there are divisions of culture or society or simply of invented categories – well, that does make it all the harder.

AF: [Regarding the observation you made about] Motti Lerner’s work: the in-between-ness of his characters. Aren’t Chekhov’s characters in-between as well? In many cases they are playing roles that are not appropriate for the classes to which they belong.

Bensussen: I think Chekhov captures the extraordinary challenge of being alive, conscious, caring, aware. The folks in Cherry Orchard discuss mortality, aging, loss, and they do so with a great sense of humor and humility. Well, most of them! They feel their size in the large context of the world, or allow us to see both how small and how important our lives are. But to the specificity of your question – yes, like in Motti’s work (and he wrote a book about Chekhov [According to Chekhov (2011) – English translation forthcoming], did you know?) the characters are trying to make sense of themselves and their roles in a shifting and difficult society.

Ian Thal is a performer and theatre educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere, and on occasion served on productions as a puppetry choreographer or dramaturg. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and is currently working on his second full length play; his first, though as-of-yet unproduced, was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. Formally the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report

Tagged: Actors' Shakespeare Project, Anton Chekhov, Goethe Institut-Boston, Israeli Stage, Melia Bensussen, Motti Lerner, The Cherry Orchard